Splotter Spellen is, in many ways, the boardgame equivalent of a supercar manufacturer like Pagani; it’s a small company that makes expensive, small-print run boardgames that, ruleswise, are of extremely high quality, and which have lovely components, but which are also geared towards serious, high-end users. Many of them are now permanently out of print and all are relatively difficult to find.

I happen to own four. (I have not, however, had a chance to play Roads and Boats yet, but it looks awesome because you get to draw on the board a la Empire Builder. Still, no play means I will save it for another post sometime.)

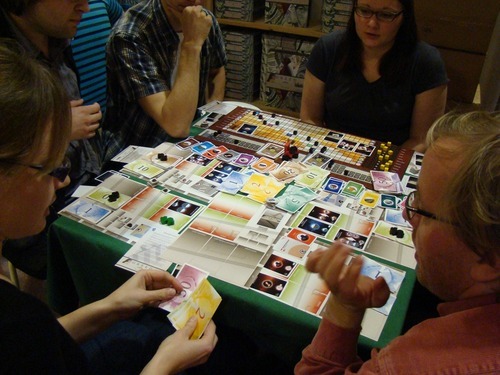

Indonesia is the easiest of the four to obtain; it is still in print (as it is arguably Splotter’s most popular game). Indonesia is a robust economic game with a lot of tweaks to it. The basic gameplay is simple: acquire companies, merge them for money, buy and sell goods for more money, and then research ways to make everything you do more efficient so you end the game with, surprise surprise, the most money. Unlike some economic games, however, there are so many variant tracks to make money with no clearly superior choice that the strategies become remarkably free-form. (One reason for this is that Indonesia offers each player the same number of “upgrades” to the various parts of the game, but there are so many upgrade options that nobody can upgrade everything, which means your choices of upgrade become a function of your playstyle and part of your overall strategy. This sort of dynamic is key to the design of most Splotter games.)

I won one game by dominating shipping lanes (and therefore earning money whenever anybody else sold goods); in another I saw another player corner the market on rice and meat and then merge them to corner the TV dinner market (yes, there is a TV dinner market in this game) and use the TV dinners to expand those cities that were placed to best advantage him, because only “his” cities had access to that crucial extra good, which meant those cities generated even more profit for him; in a third another player won with a combination of smartly placed shipping companies and oil production so that he was generating pure profit off his oil deliveries. Indonesia is a game with a lot of room to mentally maneuver, and it rewards deep play.

Greed Incorporated is an even more free-form economic game than Indonesia is, but it is the exact opposite sort of game from Indonesia. GI owes more to the Sackson classic I’m The Boss than your traditional hardcore economic game. Yes, there are companies producing goods and the primary way those companies make money is by selling those goods – but that’s not really the main game in GI. No: GI is meant to be a game simulation of pump-and-dump economics. You play the executive class, and you personally start the game with zero money: the way you get money is by forcing the companies you manage to fire you, at which point you collect a juicy golden parachute directly from the company’s profits. This means that all of the dealmaking and negotiation in Greed Incorporated becomes recognizing how to get ahead and create those situations where you will massively profit from a company’s impending bankruptcy. When you control more than one company, the dealmaking gets more and more intricate as you manipulate multiple companies to create massive, massive profits and then create downswings the very next year. Meanwhile, however, at the same time it becomes massively important that you be situated in multiple companies so that when these situations occur for other people, you can either profit from them or set yourself up to take over that company so you can profit even more greatly.

Meanwhile, as all of this is happening, the game also has a stock market to represent the values of the various goods you can produce, manufacture and sell – and the game is designed expressly to create bubbles in all of the goods and then pop them like whoa. Oh, and in order to win the game, it’s not simply about having the most money, because really, this is a game where you routinely end the game with over a billion dollars. No, the way to win the game is to use your money to buy the best toys, because GI is a game that recognizes that the only people that rich people envy are other rich people who have better stuff than them. Which means you bid against other players to buy the best toys (private jets, personal islands, trophy wives, et cetera) – but since whenever a toy gets bought, the next toy (which will be an even better toy in terms of winning the game) has as its opening price whatever the previous toy sold for. Which means that a lot of the battle for the best toys is about making other people overpay for a toy and then immediately buying a better one at the same price.

It’s a hilarious game, but unlike a lot of funny games, it’s a funny game that you can play completely straight because while it’s funny, it’s not “Munchkin funny” (i.e., not funny); the hilarity comes as you do horrible things to make money.

Finally, the most expensive Splotter Spellen game I own is Antiquity. An aside: people have often asked me why I hate Agricola. The answer is multiple: I hate Agricola because it’s largely a non-interactive game where you are primarily concerned with your own board, and I hate Agricola because although it offers the promise of variability (through the different worker/job cards) in truth it really doesn’t because Agricola’s scoring system is set up so that everybody is ultimately pursuing the same set of goals, and I hate Agricola because it pretends to be this brutal punishing game but it never follows through on that, and I hate Agricola because it is about fucking farming.

Dave Lartigue, when I mentioned playing Antiquity on Twitter, responded by saying “Antiquity is the game Agricola players think they’re playing.” Which is more or less accurate, I think. Antiquity is somewhere in between being a civ-game and a farming game, and the core of it feels like Agricola in that you are desperately trying to manage your resources and expand to win the game.

Except that:

1.) Antiquity forces you to think about sustainability. The game has a famine mechanic, which forces you to have more food every turn in order to avoid placing graves in your city (and graves are bad, because they take up space for your improvements and then start deactivating your improvements), but in order to get more workers or increase your territory around the city or even start a farm, you need to spend food to do so. The game also has a mechanic it calls “pollution” – when you harvest a resources outside of your city, you place pollution markers there to show that you have taken everything of value from that hex. On top of that, you have to place additional pollution counters within your “zone of control” outside your city every turn to represent the garbage and shit your city produces every turn. If you can’t place those counters? More graves! If you can’t place graves? You lose the game immediately. This tense race against the game’s clocks starts on turn one, and right from that point you constantly feel the famine and pollution breathing down your neck as you try to simultaneously expand and avoid collapse.

2.) Antiquity is much more interactive than Agricola. The game takes place on a single map; this means everybody is expanding into the same central territory and trying to claim resources as quickly as possible. It also means that expanding your territory to cross into other player’s territory becomes a vital aggressive tactic because now you can dump pollution into your opponent’s territory. One of the buildings allows you to trade resources either with the game (as per Settlers of Catan) or with other players, and since not everybody bothers to build this building, building it and operating it can effectively turn you into a bank for the other players.

and 3.) Antiquity forces you to choose your own victory condition. When you build a cathedral, you get to pick one of five patron saints to whom you will dedicate said cathedral. The saint you choose will give you a special power and determine how you will win the game. Since you typically don’t build the cathedral until a third of the game is over, this means you can alternately immediately begin building towards your first choice of win condition or pivot to a different one as need be. You can pick a deeply interactive win condition (completely surrounding one opponent with your own buildings in the countryside) or a totally isolationist one (build every city building in the game). Antiquity, unlike Agricola, lets you choose your playstyle and play to your strengths – if you can prevent your opponents from taking advantage of your weaknesses.

Related Articles

12 users responded in this post

I’m The Boss is one of my favourite games, but now all I can think of is how bad I want to play Greed Incorporated.

Oh how I wish everyone I knew who played board games hadn’t moved away from the city.

It might be useful to point out that cities in Indonesia are not “owned”, despite your implication that they might be. It’s useful to own resource areas that are “near” a city where you own the boats between your resources and the city (because then you don’t pay another player for shipping). But the cities are all shared resources, and the only things determining which boats get used to ship goods to which city are boat-shipping-capacity (each ship can only get used to ship so many of your goods) and city-size (each city can absorb only so many goods).

It’s a shame you also didn’t provide an overview of Duck Dealer. Despite the goofy name, it’s another excellent player-entwined economic game from Splotter with relatively simple rules and deeply emergent play. Like Ticket To Ride, the game employs the interesting tempo governing mechanic of letting you each turn decide whether you want to gather energy for later use, or spend your gathered energy on actions. Unlike TTR, it poses no limit on how much energy you can spend to act. The game, therefore, poses an interesting brain-burney problem for players: it’s not just about the “save or invest” conflict, it’s also about trying to spend as efficiently as possible and chaining a whole bunch of actions together in a bewildering and brain-hurting sequence. Highly recommended.

It’s a shame you also didn’t provide an overview of Duck Dealer.

I owned Duck Dealer for about five minutes before trading it for GI, which I wanted more. It’s on my to-get list, though.

All right, ya hipster geek, I’ve got a copy of Antiquity coming my way. This better be as good as you say.

Yay, board game posts!!

MGK, have you tried your hand at Dominion at all? (Granted, not a board game, but wanted to ask regardless)

Hey, random question – have you ever written a post on good 2-player games? Generally my wife and I play a lot of boardgames, but we’ve run out of good 2-player ones, recently.

@Gravy Express: MGK has not only played Dominion, he has played so much of it that he’s burned himself out on it at LEAST once.

@MGK: MGK, I love all your boardgame posts. I have purchased Eclipse based solely on your recommendation. May I make a small request that you may or may not honor as you see fit?

Any chance we could get a ‘MGKs Top Ameritrash Picks’ post or something equivalent? When you talk about your personal recommendations or do reviews, its always exclusively euros, or at least games that fall heavily on the euro scale. I think the only ameritrash I’ve seen you review was King of Tokyo.

Don’t get me wrong, I love me some euros. But I also love things like Arkham Horror.

I managed to get a chance to play the game Rise! (Crash Games) last week, and loved it. It has simple mechanics that still manage to lend themselves to acts of great sneakiness and treachery.

I got a chance to try a friend’s copy of Roads&Boats a while back, and was pretty impressed with it.

At first it seems like just another engine snowball game, where you build buildings which produce resources, and other buildings which turn those resources into scarcer ones, and finally you get points out the end of the process. But complicating matters is 1. the tight map, with other players competing for space 2. some of the buildings don’t make resources, but modes of transport (you start off with mules, but can make trucks, rowboats, steamers, etc.) 3. you don’t own anything except these transports and the goods they carry. This means that you can cooperate and build a building between you and the other player, then share in the use of it, or go first and make an end run into their territory to steal the gold that’s been accumulating on their mines.

The final thing which makes it great is that as all this is going on, there is a ‘wonder’ project that all the players are contributing to and earning points. So, there’s a tension between climbing the tech tree to make as much as you can of the few things that are worth points, and enough trucks to warehouse them in -or- just building the wonder as fast as you can to shut out the players going for tech.

I’ve known about Antiquity for a while, and I’ve thought about purchasing it. But I have four problems with Antiquity, only one of which MGK alluded to.

1) It’s only four players. My group is usually five to six, so I already own far too many excellent four-player games.

2) It’s a three-hour playing time. At my game nights we usually play three or four or five games, with a variety of styles so that everyone at the table plays something they really like, and so that nobody spends half the evening playing a single game they know they’ve lost from round three. Three hours is at the far end of the curve for us, barring those occasions where we block off a whole day for a single epic game. So again, Antiquity wouldn’t get to the table very often.

3. Can’t find it. Out of print for a long time, never coming back.

4. If you can find it, it’s going to start at $150 and go up from there, likely plus an exorbitant shipping charge from the US or UK. I’ve paid silly amounts of money for games before (TI3, Puerto Rico: Anniversary Edition, Eclipse wasn’t cheap), but nothing like $150+, and most are in the $40 – $50 range. Buying Antiquity means not buying four other games.

Antiquity is good, but is it four times as good as the four games I might buy otherwise and would actually play more often? Nope.

I hear on Munchkin not being funny. I first played it among fellow RPG geeks who all could appreciate the puns (and the illustrations, some of which I still find quite funny) and who all could get in the spirit of the game, having the necessary cultural training. I assumed that the game itself was fun, rather than the environment.

I have since tried taking the game out of the environment and introducing non-nerds and non-RPGers to it. It’s fallen flat every time.

You haven’t played Roads & Boats yet?