23

Jun

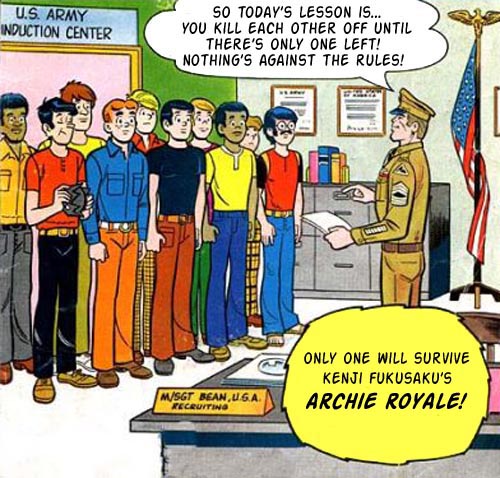

Not Quite Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

8

Jun

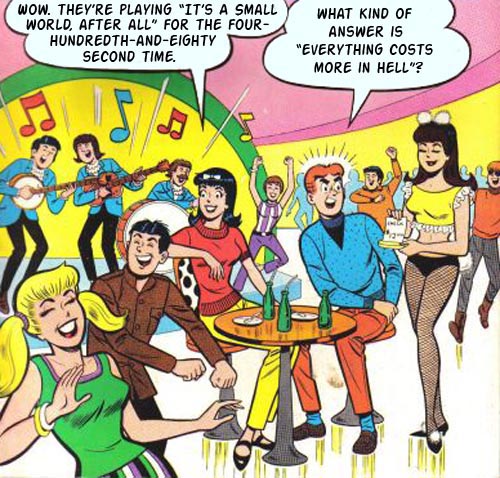

Not Quite Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

27

May

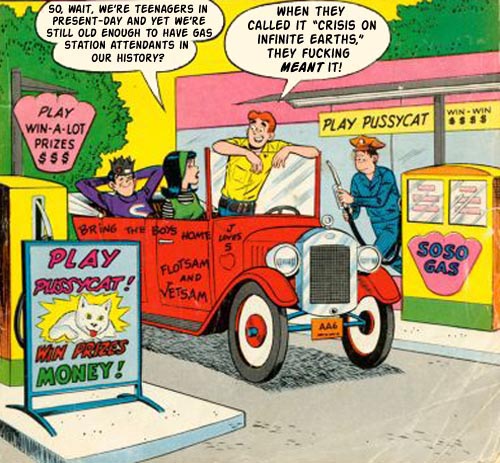

Not Quite Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

15

May

Some Insane People Are Not Named Betty Cooper

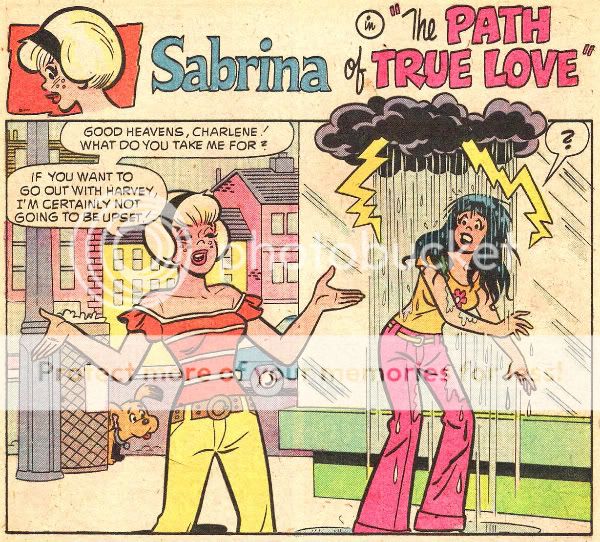

Posted by Jaime Weinman Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, WTFThe one thing Archie Andrews can be thankful for is that Betty Cooper doesn’t (usually) have god-like magical powers that allow her to kill or maim other people on a whim. Harvey… er… No-Last-Name is not so lucky. As revealed in this story from Sabrina # 21 (September 1974), written by Frank Doyle and drawn by Stan Goldberg before his characters’ faces started melting, Sabrina has adopted a policy of talking nice to her boyfriend while quietly using her Satanic powers to wreak destruction on any girl who even looks his way.

The violence begins in the splash panel, as Sabrina congratulates herself on her own lack of jealousy while literally raining thunder and lightning down on this poor girl whose only crime was to be (inexplicably) interested in Harvey. The whole thing has a “why don’t you stop drenching and electrocuting yourself” feel too it.

Then, after the girl has made it clear that she’s been thoroughly scared away, Sabrina tries to murder her by making a heavy sign fall on top of her. Just for the hell (again, literally) of it. Also, “Eeyipe!” was clearly a favourite Frank Doyle word along with “EEP!” “Urk!” and “W-ell.”

The freckled hell-spawn then returns to telling her poor sap of a boyfriend how wonderful he is, but senses danger when a stranger winks at him. So of course she does what anyone would do in a situation like that: causes her to have an entire supply of garbage poured onto her. I guess she was allowed to escape without any permanent scars only because she didn’t actually talk to him.

And, as the story ends, we see Sabrina casually destroying the lives, bodies and futures of literally every other young woman in sight, because it’s better to turn them into reptiles amphibians or cast them down to the centre of the Earth rather than risk having them talk to a guy who would later be played by Nate Richert. (Whatever happened to Nate Richert anyway?) I think my favourite image is of the girl being pulled into a mysterious building with a “girls wanted” sign. Apparently Sabrina is also using her witchcraft to sell women into prostitution.

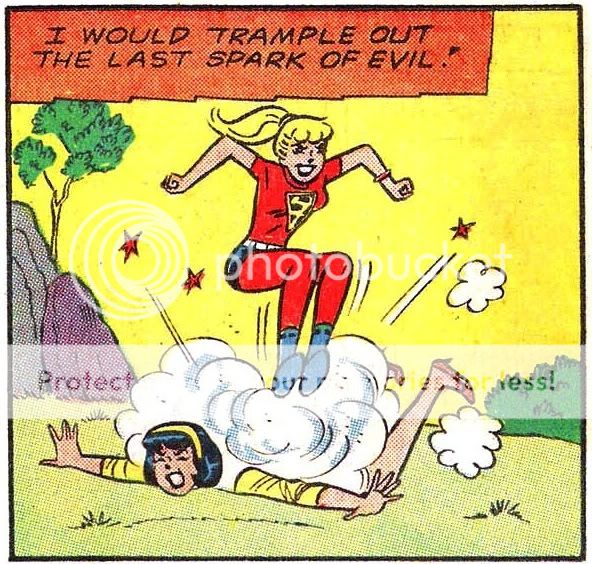

I just wonder what Betty Cooper would do if she had supernatural powers. How could she ever top Sabrina’s combination of cruelty, viciousness and pathology?

I’m sorry I asked.

12

May

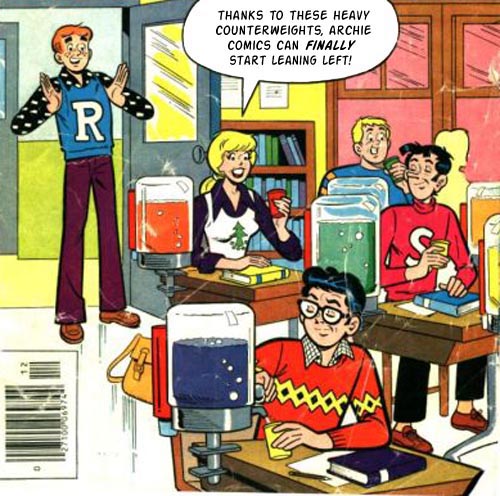

Not Quite Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

28

Apr

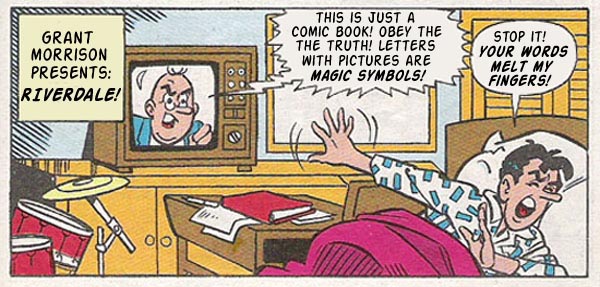

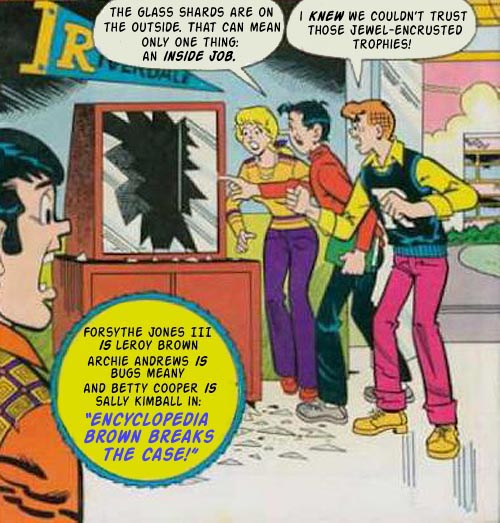

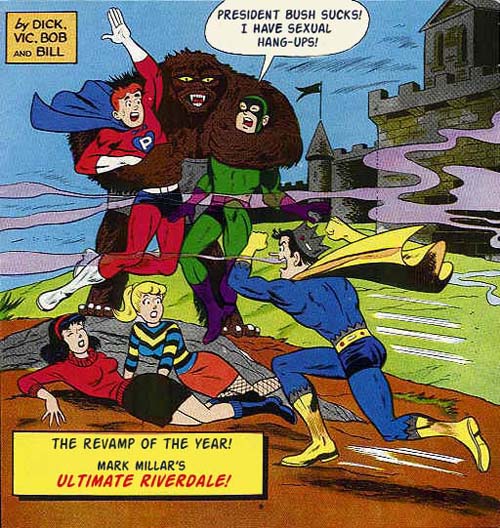

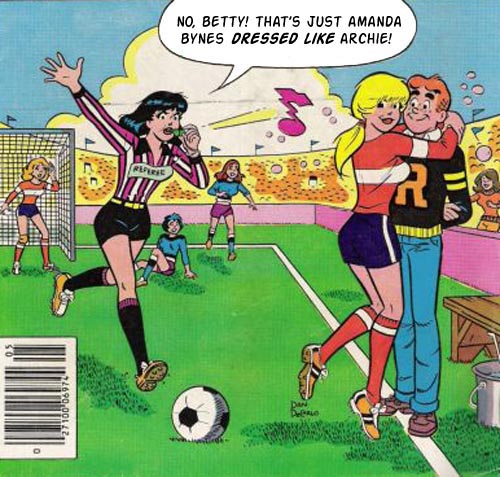

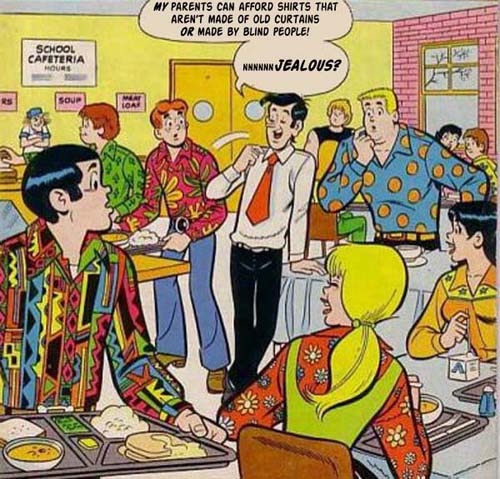

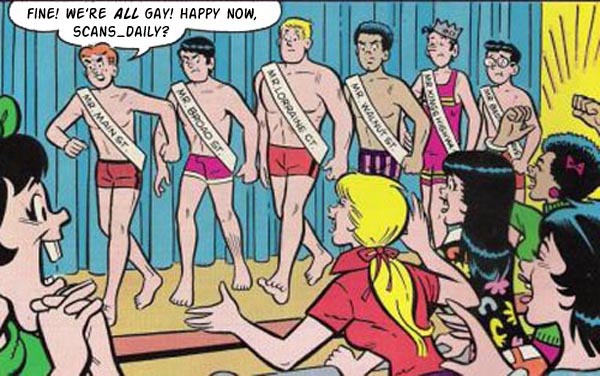

Since people were wishing for the return of Improved Archie, here it is, in very very basic form:

Have at it in comments.

Also, I’m looking for artists for a couple of projects – you know the email if you’re interested in working with me.

26

Apr

As requested, part two

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Bad Comedy, Comics, Here's A Lot Of Photoshops, Photoshopp'd

24

Mar

Comics Between The Panels, and Also In Silhouette

Posted by Jaime Weinman Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), ComicsEvery so often I get a comment on my blog that makes blogging worthwhile. One of them is this comment I got on a post about comic book artist Samm Schwartz:

I’m Sam Schwartz’s daughter. I googled him and was surprised to see a substantial number of hits. I think it’s terrific that people are still talking about him!

(No, she’s not mis-spelling her father’s name; as his Wikipedia entry notes, his name was actually “Sam,” and most people called him that in everyday life, but at some point in the ’40s he started signing his drawings “Samm.”)

Well, that got me thinking a bit more about Schwartz, the first comic book artist whose style I could identify as a child. And so did this post by veteran artist/inker Kevin Nowlan about some pages of original Schwartz art and how good Schwartz was at making characters fall down. So I decided I’d comment on a different Schwartz story:

The story is called “A Loan and Blue,” written by Frank Doyle and drawn by Schwartz (who, as usual, inked and lettered the story as well), and you can click here to read the five pages.

Now, one thing that I can’t really put into words is that Jughead has a bigger range in Schwartz’s stories than he does elsewhere. He’s not exactly a character you can do a lot with, visually, but Samm always seemed to understand how much could be conveyed by having him open his eyes at the right time (or open his eyes halfway instead of all the way), or putting some extra folds in his very simplified clothes.

But the story does illustrate a few tricks Schwartz was in love with:

1. Letting the characters violate the panel boundaries. This wasn’t a new technique or anything; it was especially common in the Golden Age. But as the technique became less common, Schwartz started to use it more often to put extra interest into the pages. After he left DC and came back to Archie in 1969, he used this in virtually all his stories. Characters’ legs and arms simply go wherever they want to go.

2. Silhouetting. There’s actually only one silhouette bit in this story, which is unusually low for Schwartz; his motto was “when in doubt, silhouette,” and there’s one story where he just did an entire page of nothing but silhouettes. I don’t know if he did it as an experiment or if he was just running behind schedule, but it sure caught my eye as a kid.

3. Eliminating panel lines and backgrounds. This story has no plot — like a number of Frank Doyle scripts, it’s just two guys talking about not a whole lot. But there is a structural spine to the script, as Jughead becomes more and more angry about the scenario he imagines. (It helps that he’s basically right. Archie is an idiot and this is exactly what he would do.) And as Jughead gets more involved in acting out this scenario, Schwartz sometimes lets multiple Jugheads float across a white space as he gets caught up in his fantasy.

4. Keeping stuff out of view. It’s Archie, rather than Jughead, who does this here, but Schwartz sometimes liked to figure out what he could get away with not putting in the panel. So Archie has a rubbery, broad reaction to Jughead’s line — but all we see of him are his legs; otherwise we’re left to imagine what his reaction was. In the late Joe Edwards’ interview with Jim Amash in Alter Ego magazine — which is a treasure trove of information about MLJ/Archie — he recalled “a story where the dogs were chasing [one of the characters], running, and Sam drew the panel so all you saw was the tail wagging.”

IDW will presumably get around to doing a Schwartz collection in their upcoming Archie artist tribute series; in the meantime, here’s Schwartz in his own words. In 1980 he wrote the following to a young aspiring writer, Craig Boldman, who now writes the Jughead comic book (this quote is courtesy of Boldman, who hopefully will put the original letter up on his website).

-

“I’m delighted that I could make you laugh. That’s the name of this game… The prime purpose of the artist is to tell the story, with pose, gesture, expression, all of it relating to the dialogue and the character involved… The comic book is not a vehicle for display of talent. It’s assumed the artist has already reached a stage of professionalism or he wouldn’t be there.”

I think of this as an acknowledgement that his spare, stripped-down style was not because he couldn’t draw any other way, but because he didn’t want anything to detract from his ability to sell the jokes.

And, for an example of Schwartz’s later work, this silhouette-filled 1980 story was always one of my favourites in the decades old “Jughead plays cruel psychological mind games on Reggie” genre. (You know, if it weren’t for the fact that all his friends are idiots who deserve this kind of treatment, Jughead would be kind of a dick.) Note the background gag on page 5: as a paper airplane crashes to the ground, a tiny pilot apparently parachutes out of it. And that’s pretty normal compared to some of the other unscripted stuff Schwartz drew into the halls of that high school.

8

Mar

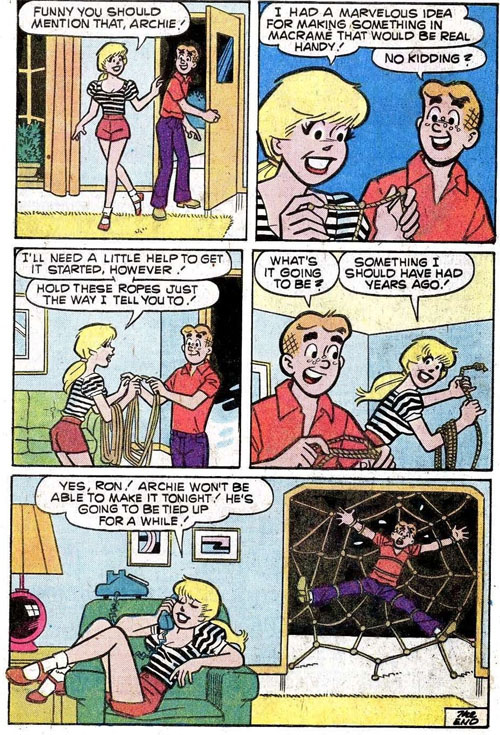

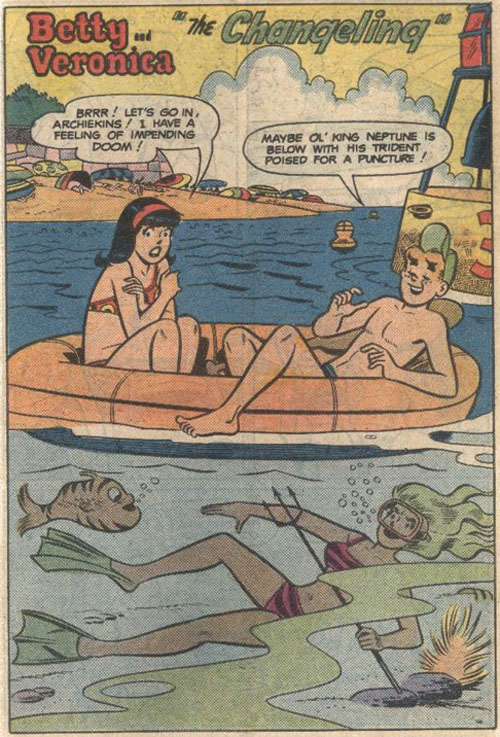

Jaime found this and passed it along:

It’s the blissful expression on Betty’s face, combined with the sheer terror on Archie’s, that really sells the last panel. Her parents are away on a weekend vacation. Jughead is in Shelbyville at a chess tournament. Veronica is distracted, thanks to tipping off Reggie that Archie would be “otherwise occupied.” Moose and Dilton are useless. Archie is all hers, and as she lies glibly to Ronnie, she knows at last the sweet taste of triumph.

24

Feb

She Also Has a Drug Problem, Of Course

Posted by Jaime Weinman Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), ComicsOkay, so let’s say I told you that in 1964, a comic book character was so out of control that the doctor prescribed tranquilizers. Let’s also say that this character started taking the tranquilizers and immediately became prone to narcolepsy. And let’s throw in the fact that even in a state of drug-induced narcolepsy, this person couldn’t stop stalking two other characters and making their lives miserable. Which character do you think I’m talking about?

I’ll give you three gu… aw, hell, you’ve guessed it already, haven’t you (click on thumbnails to read the pages).

The story more or less speaks for itself. Well, the ending might need a bit of explanation. Suffice it to say that tranquilizers, sedatives and other knock-out pills were at the height of popularity in the early ’60s. So a comic book about two teenagers choosing to take someone else’s clearly dangerous prescription drugs? Not a problem. I mean, it’s not like they’re drinking beer or something.

And a question for experts on Betty Cooper’s mental state: do you think her doctor prescribed this incredibly strong medication because he was trying to take her out of commission, or is this just the dosage she prefers?

Finally, those who like spotting hidden messages in old comics might note the names and initials on the bench:

“Dan” and “Josie” are Dan DeCarlo and his wife (yes, that’s where he got the name) while “Rudy” and “Mary” are DeCarlo’s inker Rudy Lapick and his wife. “Harry” is probably Harry Lucey. And LBJ might or might not be a politician of some kind. That one’s for comics historians to decide.

18

Feb

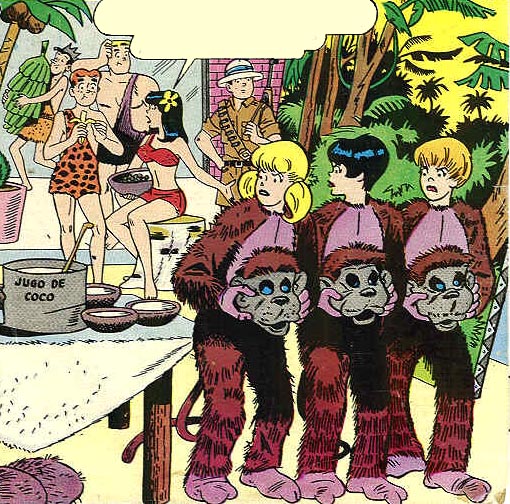

Learn Spanish Or the Kid Gets It

Posted by Jaime Weinman Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), ComicsYou know what surprises me about remakes in comic books? It’s that there haven’t been more of them. Formula or no formula, there does usually seem to be a presumption that a new script is better than re-illustrating an old one from a decade earlier. Which is a good thing; I’m just not sure if it reflects integrity or the fear that someone might notice. Anyway, Archie comics had surprisingly few out-and-out remakes for a franchise where a lot of the stories kind of feel like remakes. But there have been a few exceptions, starting with two versions of one script that told us the same thing: if you don’t learn a foreign language, people will die.

The first time this script appeared was in 1960, in Archie # 114, a story that inspired one of the most famous Harry Lucey covers (Ren and Stimpy creator John Kricfalusi, a Lucey admirer, featured it in his blog’s Lucey cover gallery.) The company at this time was going through one of their very brief flirtations with having the cover actually be related to the stories inside, instead of being a stand-alone gag…

…but, like most such covers, it gives a false impression of what’s going to happen; we think Archie’s going to be arrested, but then we open the book and find:

Pretty straightforward message: you may not like studying Spanish, but you should learn it anyway. Why? Because when a kid gets hit by a car, every single other person in the crowd will have been too apathetic to learn Spanish themselves, and you’ll be literally the only one who can talk to the kid’s father and find out his blood type. That seems hard to argue with.

The story must have made an impact on someone at the company, or they just wanted to do something like it and didn’t have time to get a new script: because sometime in the late ’60s (judging by the art and clothes, it looks like 1969 or so), they did it again.

Archie’s R sweater and bow tie are gone and Betty is now wearing miniskirts, but the art is basically the same, though there are enough new poses to suggest that it was re-drawn rather than just re-inked from the old drawings. (I’m sorry that I couldn’t get them side-by-side for direct comparisons.) Lucey, who was an excellent superhero/action artist and is credited with having done some Captain America work in the ’40s, still draws the authority figures (the cop, the surgeon) in a less cartoony style than usual. But what we learn primarily is that despite all the social upheaval between the beginning and end of the ’60s, there’s still no one except Archie who can speak Spanish.

Now, as I said, comic books wouldn’t normally dust off an old script and do it verbatim; they’d do a similar story with a new script. And that’s what they did sometime in the mid-’70s, in the adventure-laden world of Life With Archie (I don’t know which issue). The script is identifiable as the tireless Frank Doyle — basically, if someone says “EEP!” it’s probably him — but the art this time is by Stan Goldberg.

The art is streets ahead of what Goldberg is turning out now, though I much prefer Lucey’s take on the characters, and you notice that his use of very prominent face lines is already getting out of hand: on page 6, panel 3, it makes Veronica look weird. But the art is not all that’s changed. Now there’s a new reason for learning Spanish. Not because a kid will get hit by a car, but because a hemophiliac kid will get a cut and you will be the only one who knows he isn’t a sissy for getting upset. And whereas in the ’60s it was reward enough to “be proud of yourself,” in the ’70s, that’s just not enough unless you also get a big kiss from the kid’s hot older sister.

But here’s where it gets strange. What’s Archie Comics’ attitude towards other languages besides Spanish? Well, as this late ’50s story from Wilbur (written by Doyle, art by Dan DeCarlo) will show, it’s extremely negative.

According to the comics, and contradicting everything I was told in the Ontario school system, French has no practical use whatsoever, and even people who speak French don’t actually care about teaching it, they just want to score with younger boys.

So, to review: if you don’t learn Spanish, the blood of dead children is on your hands. But watch out for French. It’s dangerous.

9

Feb

Department of Confusing Cold War Allegories

Posted by Jaime Weinman Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics

In lieu of a somewhat more substantive post that I’m still tinkering with, here’s a 1964 comic book story whose Cold War origins have always confused me. Not that it’s confusing that a science fiction story would be about the Cold War; what else was it going to be about? The question is, who’s who in this particular Cold War conflict.

(I decided to stop trying to YouTube stories; breaking this story up into its separate panels would ruin some of the effects — like the the “circle” bit at the top of page 9, the comics equivalent of the way a movie cuts from an exterior to an interior and back again.)

Now, okay, the Cold War markers are fairly clear, as you would expect in a science fiction story from the year that Mad Men will soon get to. You’ve got Planet Zentrox, the thriving tourist-friendly place, vs. Planet Glob, the ugly, drab conformist hellhole where everybody looks alike. The President of Zentrox even has a teenage daughter; she’s called Zeena instead of “Lynda Bird” or “Lucy Baines,” but we still get the point. Just in case we’re wondering what this is about, we get this rather late in the story:

But the weird thing about this Cold War story is that the bad guys are religious bad guys, who are defeated when our hero exploits their doctrine and makes them think that God is displeased with them. So in allegorical terms, the story seems to present the Globs as God-fearing Communists whose religious belief renders their military might useless.

The message of the story, apparently, is this: The side that believes in tourism, sports cars and construction work will win out over the side that’s held back by religion. Provided, of course, that Little Archie gets abducted by aliens and shows up to help, but he gets abducted by aliens all the time, and occasionally finds aliens in his refrigerator, so it was inevitable that he’d be involved in any interplanetary conflict.

Now, my guess would be that this plot might come from an earlier science fiction story or film, the way Bolling’s “Plesiosaur” is inspired by Ray Bradbury’s “The Fog Horn.” If I knew what the inspiration was, the point of the Zentrox-vs.-Glob conflict might be a bit clearer. (One of the reasons I did this post was that I figured someone might know what this is based on.) But as it is, the way the story reads for me, it’s like the Godless capitalists beat the religious planet.

As to how Little Archie Andrews managed to get the entire planet made over in so short a time… he can do pretty much anything. Even at this age, he’s already begun to have an inexplicable magnetism for women:

Wait in line, Lynda Bird Zeena. Wait in line.

Finally, for a lighter side of Bolling and outer space, I wanted to throw in a (somewhat late) reciprocal link to Doug Gray and the classic 1959 story “The Shrimp From Outer Space.”

Gray’s blog, The Greatest Ape, collects stories by non-superhero comics masters like Barks, Bolling, Kelly, John Stanley (Little Lulu) and Al Wiseman (Dennis the Menace). You can spend a lot of time reading the great material there, but it’s time well spent.

26

Jan

Jughead Jones: Male Prostitute

Posted by Jaime Weinman Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, WTFThe year is 1958. The month is June. The teenagers of small-town America are filled with a nebulous sense of rebellion against repressive sexuality and social convention. It was inevitable that some business genius would make money off their forbidden longings. A proto-beatnik named Forsythe P. Jones opens his own “escort service,” which involves not only renting himself out to all the women of Riverdale, but wearing any disguise that suits their kinky fantasies. He even tries to expand the business by taking on Reginald Mantle as a sort of junior gigolo, to take up with women who are too scary for the boss to handle himself.

I’ve once again done the embeddable YouTube video thing, but some of the panels are hard to read in this format, so you can also click here to see the story with the original page layouts. (For those who care about such things, Archie comics had a lot more panels in the late ’50s and early ’60s than they had before or after. Sometime in the ’60s most of their artists switched to a rule whereby there couldn’t be more than six panels per page.)

Also, an important principle that Dan DeCarlo followed in his ’50s prime was that girls’ skirts must be flowing in the breeze whenever possible. Riverdale must have been some windy town.

One thing I’ve been wondering for years is whether “It sounds creamy!” was actually a slang phrase of the time or if it’s just a vaguely dirty-sounding substitute for “dreamy.”

6

Jan

Betty Cooper, Amnesiac Mud Wrestler

Posted by Jaime Weinman Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, WTFI don’t think any comic book of the ’70s had as much insane shit in it as Archie at Riverdale High. And that’s saying a lot, because we are talking about the ’70s here. But this title, launched in the early ’70s as a home for “serious” stories focusing on academic or athletic issues, packed an impressive number of WTF moments into its bi-monthly issues. You could pick up an issue at random and find: Archie beats up the members of a rival school when they “touch his body with a Central High towel”; a famous painter agrees to paint Mr. Weatherbee on condition that Archie will pose for him in the nude (which he does); Archie infiltrates another rival high school in drag; Archie uses special-effects technology to convince everyone that a kid is actually a superpowered alien named “Nazda.” Many of these stories were also full of floridly melodramatic captions, a possible throwback to Frank Doyle’s early days writing and drawing “Space Rangers” and “Wambi, the Jungle Boy”.

You can make an argument for the higher weirdness quotient of Life With Archie, where Archie spent the ’70s battling Satanic, child-murdering teddy bears, but that title always had fantasy/alternate-universe stuff. But what happens to a kid’s brain when he picks up a comic about high school adventures and is treated to a story like this one, where Betty loses her memory, wanders off and becomes a mud wrestler? And then the only way for Archie and Jughead to save her is for Jughead to disguise himself as a woman, and what is it with this title and men in drag, anyway?

I turned this into an embeddable YouTube video because it’s just easier to post that way. The Hector Berlioz music is just meant to speed the story along and the choice is not of any significance, though I take pride in the fact that the big cymbal crash coincides with the key moment in the whole story: Jughead’s realization that Archie wants him to make The Supreme Sacrifice. Which, as I mentioned, involves drag.

That story pretty much speaks for itself. I do want to point out one thing that has haunted me since young me encountered this in a digest. Understand, I don’t believe in nit-picking the plot holes in anything, let alone comic books. Pointing out every plot hole as if each one is some kind of crippling flaw is almost as bad as pointing out every continuity goof in a movie. All that said:

This previously-unknown kid who goes to the carnival — he has to be a new kid because they couldn’t let any of their regulars willingly go to such a “sleazy outfit” — sees a girl from his school who has been missing for days, maybe weeks. His first statement after recognizing her is “I’ve got to call Archie.” I’m just saying, if this guy thinks he should call Archie before notifying the police… or her parents… or even the principal… then he is so dumb that he probably walked into an open manhole as soon as this story was over. And that explains why we never saw him again.

The other important lesson from this comic is that you can learn a lot about characters from what they say when Jughead throws them Helluva Far™. Betty says “EEP!” like all good-hearted people. Stan Snavely exclaims “AIEEE!,” like some Jonny Quest villain. That’s how we know he’s evil.

21

Dec

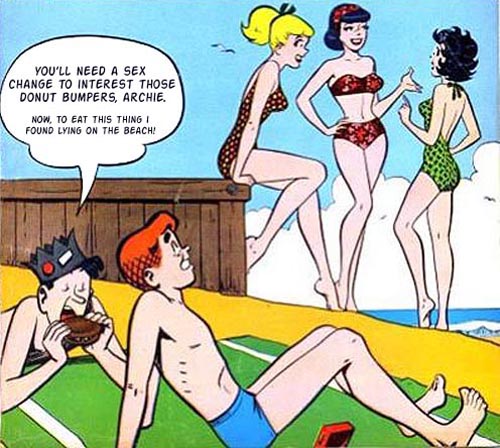

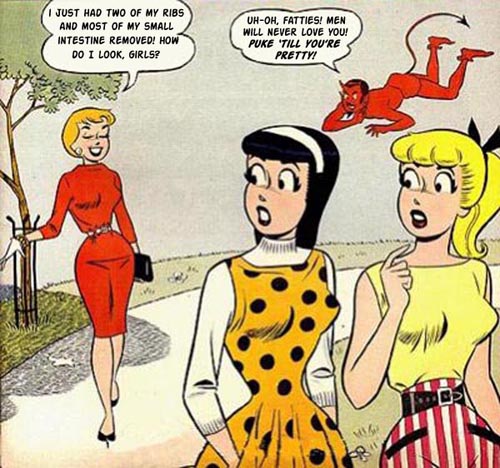

I feel this needs no further elaboration.

Search

"[O]ne of the funniest bloggers on the planet... I only wish he updated more."

-- Popcrunch.com

"By MightyGodKing, we mean sexiest blog in western civilization."

-- Jenn

Contact

MGKontributors

The Big Board

MGKlassics

Blogroll

- ‘Aqoul

- 4th Letter

- Andrew Wheeler

- Balloon Juice

- Basic Instructions

- Blog@Newsarama

- Cat and Girl

- Chris Butcher

- Colby File

- Comics Should Be Good!

- Creekside

- Dave’s Long Box

- Dead Things On Sticks

- Digby

- Enjoy Every Sandwich

- Ezra Klein

- Fafblog

- Galloping Beaver

- Garth Turner

- House To Astonish

- Howling Curmudgeons

- James Berardinelli

- John Seavey

- Journalista

- Kash Mansori

- Ken Levine

- Kevin Church

- Kevin Drum

- Kung Fu Monkey

- Lawyers, Guns and Money

- Leonard Pierce

- Letterboxd – Christopher Bird - Letterboxd – Christopher Bird

- Little Dee

- Mark Kleiman

- Marmaduke Explained

- My Blahg

- Nobody Scores!

- Norman Wilner

- Nunc Scio

- Obsidian Wings

- Occasional Superheroine

- Pajiba!

- Paul Wells

- Penny Arcade

- Perry Bible Fellowship

- Plastikgyrl

- POGGE

- Progressive Ruin

- sayitwithpie

- scans_daily

- Scary-Go-Round

- Scott Tribe

- Tangible.ca

- The Big Picture

- The Bloggess

- The Comics Reporter

- The Cunning Realist

- The ISB

- The Non-Adventures of Wonderella

- The Savage Critics

- The Superest

- The X-Axis

- Torontoist.com

- Very Good Taste

- We The Robots

- XKCD

- Yirmumah!

Donate

Archives

- August 2023

- May 2022

- January 2022

- May 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- June 2020

- March 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- February 2007

Tweet Machine

- No Tweets Available

Recent Posts

- Server maintenance for https

- CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards

- CALL FOR NOMINATIONS: The 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards (the Theszies)

- The 2020 RSPW Awards – RESULTS

- CALL FOR VOTES: the 2020 Theszies (rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards)

- CALL FOR NOMINATIONS: The 2020 Theszies (rec.sport.pro-wrestling awards)

- given today’s news

- If you can Schumacher it there you can Schumacher it anywhere

- The 2019 RSPW Awards – RESULTS

- CALL FOR VOTES – The 2019 RSPW Awards (The Theszies)

Recent Comments

- George Leonard in When Pogo Met Simple J. Malarkey

- Blob in How Jason Todd Went Wrong A Second Time

- Cindi Chesser in Thursday WHO'S WHO: The War Wheel

- Scott Hater in Bing, Bang, Bing, Fuck Off

- dan loz in Hey, remember how we talked a while a back about b…

- Sean in Server maintenance for https

- Ethan in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…

- wyrmsine in ALIGNMENT CHART! Search Engines

- Jeff in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…

- Greg in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…