The Law Society of Upper Canada is currently considering whether to revise/revamp the articling system or abolish it entirely, and more or less the entire legal profession in Ontario – and by extension Canada, because as goes Ontario, so will eventually the rest of the nation – has an opinion about it.

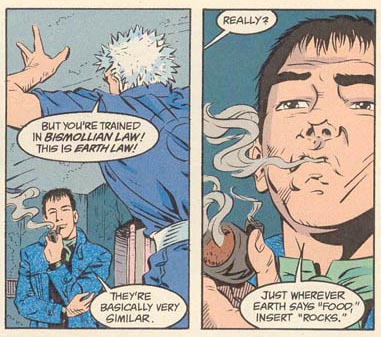

For those who are not Canadian lawyers or even lawyers elsewhere: articling is a requirement in each of Canada’s provinces (each of which has its own independent law society) in order to join the bar. The basic idea behind articling is: after you graduate law school, you work for ten months for a lawyer, and essentially learn on the job. Law school, you see, does not actually teach you a lot about the daily nuts and bolts of legal work, but rather “how to think like a lawyer.” (Which is actually a thing. We will pause the post here for all of you to get the lawyer jokes out of your system. Trust me as a member of the profession when I say we invented most of them.)

The problem with articling is that there are not enough articling positions to go around – this year, estimates are as low as there being only 80% of graduating students who will find articling positions. And of course, that 20% who don’t find them are then competing with next year’s graduating class, so you have 120% of a graduating class competing for 80% of articling positions. Except, of course, that the problem is that articling positions are decreasing in number and have been for years, so the problem just keeps getting worse. I am in my second year as a lawyer and know of at least one person from my graduating class at Osgoode who still has not found an article. That person’s investment in a law school education (sixty thousand dollars or more) has been, unfortunately, a bad one so far, and he is far from the only one.

I, on the whole, am for the abolishment of articling, as follows:

Proponents of articling argue that practical experience prior to being called to the bar makes for better lawyers, and I would say that this is inarguable. However, the question of whether articling makes for better lawyers overall isn’t a satisfactory answer to the question of whether articling is necessary – after all, no other common-law system in the world still has articling as a requirement for call to the bar. They’ve all abolished it. (I have no idea if Canada has a lower rate of legal malpractice claims than other jurisdictions offhand and Google has not turned anything up yet, but it seems like extremely relevant data.) I think people arguing for the continuance of an additional barrier to the bar that doesn’t exist anywhere else do have an affirmative duty to justify why it should remain, and that argument has not yet been made.

Moreover, I think the overall value of articling is extremely loose – there is no real guarantee that an article will provide serious legal experience worthy of the hassle that getting the article (which, even in an ideal full-employment situation, is still a grueling round of interviews more often than not) represents. (I personally was quite lucky to article with a principal who strongly believed in exposing his articling students to as many different aspects of his practice as possible.) Here, Lee Akazaki argues that the uneven quality of articles is a straw man argument because no article can properly prepare a student for all aspects of law, and the most important thing is to teach lawyers through groupwork and expose them to the demands of professionalism. Which isn’t a terrible argument, but there should exist minimums of exposure to a wide area of legal work. Effectively, this is impossible to regulate. As it stands right now it is already difficult enough for a student to bring a complaint against a principal if necessary (to say nothing of the fact that due to the inherent imbalances in the employer/employee relationship that articling has buried in its very nature).

This is to say nothing of the fact that the articling crisis is most intense outside of large urban centres where the profession is aging fastest. It’s not a surprise that cities attract more lawyers like they do every other type of skilled professional – that’s just urbanization – but articling presents a special problem because if small-town lawyers are to hire articling students, the fact that they are essentially training their competition hits harder than it would a big-city lawyer. (Which is, I think, one of the major reasons articling is in crisis at this point, although I admit this is based at least partly on supposition.) If the entire concept of articling works at cross-purposes for rural lawyers – and I think there is a reasonable argument that it does – then it’s by definition going to be a failed system.

But mostly, it comes down to the question of how many barriers to entry there should be for a new lawyer. Right now articling is simply an additional barrier on top of getting into law school, finishing it and then passing the bar exam (none of which are exactly easy) and so I would argue is effectively redundant. There are other ways to properly introduce students to the actual demands of the profession, the most obvious of which being including a large practical component in the third and final year of law school (which is of dubious value, to say the least, and Paul Campos’ experience being informed by American schools rather than Canadian does not change that much at all).

It’s time for articling to go. I understand why people want it to stick around: you want the best for the profession and it’s a safeguard. But it’s not an effective one, not any longer.