My weekly TV column is up at Torontoist.

2

Sep

because when I think “scripted programming” I think Discovery Channel

Posted by MGK Published in The Internets, TV30

Aug

Jim Shooter, for all that he is a legendarily controversial figure who was practically burned in effigy when he was booted out of Marvel and who made life miserable for a lot of people during his time as editor-in-chief, was a very smart guy and a pretty good writer. Dialogue was never his strength, but he’s always had a knack for coming up with big, interesting ideas and relating them in an accessible way. And I have to say, ‘Secret Wars’ was one of his triumphs on that score.

It started much the same way that DC’s ‘Super Powers’ mini-series did; they were doing a toy line, and they wanted to tie it in to a single storyline that featured as many of Marvel’s big guns as possible so that you would read the comic and then buy the toys…or possibly vice versa. Either way, it was a much bigger success as a comic than a toy line; the ‘Super Powers’ toys did far better business than ‘Secret Wars’ ever did. But as a comic, there’s no question which was better.

For one thing, it worked really well as a Big Event. The way that Shooter handled it made it remarkably a) non-intrusive for a crossover that involved Spider-Man, the Hulk, Iron Man, the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, the Avengers, and pretty much every single big-name villain including one who was notoriously dead at the time, and b) caused a lot of anticipation among comics fans. Shooter had the heroes disappear at the end of one issue (being the EIC of Marvel meant it was a lot easier to get people to participate in your crossover) and reappear at the beginning of the next…but as with DC’s ‘One Year Later’, a lot had clearly happened between those two issues, and the only way to find out what was to buy ‘Secret Wars’. Why did Spider-Man have a new costume? Why was the Hulk’s leg in a cast? Why was the Thing off on another planet? Why was She-Hulk now a member of the FF? Why did Colossus break up with Kitty Pryde? These were the kind of questions that Marvel could reasonably expect fans to want to know the answers to, and it was smart to structure the series this way. (And for the most part, the answers even made sense. Although the Hulk didn’t stay in the cast for long.)

But for another thing, it had some interesting themes. First, the Beyonder worked perfectly for this crossover. It made sense, on a metatextual level, that a series that was a tie-in to a toy line would involve an impossibly powerful alien playing with Marvel’s heroes and villains as if they were his action figures. But more than that, Shooter decided to ask questions about why kids enact such complicated play activities with their toys, especially ones that are emblematic of struggles over good and evil. He suggested that maybe the play activity helped sort out moral questions on a level accessible to children, and structured the series around an alien that was trying to figure out what good and evil actually were, and around an omnipotent alien whose every desire was instantly fulfilled trying to figure out what it was like to want things.

The answers he came up with were pretty interesting. For starters, although it was never made explicit, the heroes and villains weren’t grouped according to our complex moral frameworks, but according to the very simple question, “Are their desires selfish?” The people who were predominantly selfless, who used their powers to help others, were grouped as ‘heroes’, while the people who were predominantly selfish were grouped as villains. This had two immediate and fascinating results, which played out over the rest of the series. By this logic, Doctor Doom was a villain, while Magneto was a hero.

This was a major thematic component to the series, and showed a really deep understanding of the two characters. Shooter realized that for all that Magneto is ruthless and even murderous, he’s not selfish. He does what he does for mutantkind, not for his own personal benefit. Magneto would be perfectly happy with a little house in the country somewhere in a world where mutants were free of persecution; he doesn’t need to rule. While Doom…Victor might delude himself into thinking that he wants to rule the world for all the right reasons. He might pretend that he would simply be the best choice as leader, and that everything he does is for the benefit of humankind. But the Beyonder saw into his heart and knew better. That pretty much formed the underpinning of the entire story.

But of course, we needed fights and betrayals and epic feats of strength and power and big cool battle sequences and heroes distrusting each other and villains distrusting each other and Galactus being apocalyptically bad-ass and all sorts of Cool Shit, too. And ‘Secret Wars’ paid off. You got to see Spider-Man beating the entire X-Men simply by virtue of being too flippy-shit to punch. You got to see Hawkeye putting an arrow into Piledriver’s shoulder. You got to see the Hulk ripping the Absorbing Man’s arm off…and, oh yeah, holding up a freaking mountain with his bare hands. Oh, and you got to see the Molecule Man dropping a freaking mountain on the Hulk. Mark Millar wishes he could come up with an ending as cool as the ending to issue #3 of ‘Secret Wars’. There were so many great, epic Big Moments in this, and yet it never felt like Shooter was trying to shove Big Moments into his story. He didn’t draw attention to them; he just kept going with one after another exciting scene.

And it all culminated in an epically awesome last four issues. After hanging around for most of the series being enigmatic, Galactus finally decided to just eat the planet and everyone on it. (Some people wondered why the Beyonder would include a character who was pretty much guaranteed to win, but that presumes that this was a fair-play competition and not a psychological test. Finding out how people responded to learning that they never had a chance at winning would be worth studying in and of itself.) The heroes debated whether or not to sacrifice themselves and let Galactus win, in order to see his hunger permanently sated and save untold future billions, but ulatimately the whole thing was rendered moot when Doom stole the power of the Beyonder and became basically God.

This has to be one of the all-time great moments of Doctor Doom’s history, by the way. It established Doom as one of the ultimate schemers of the Marvel Universe; while everyone else was trying to figure out how to win the contest, Doom was planning to screw over God. And it worked. That’s bad-ass. And his defeat was also amazing; the heroes didn’t beat Doom with cunning or teamwork or power, Doom beat himself because deep down, he knew he was unworthy of Godhood. He couldn’t consciously accept the truth about his uglier aspects, but his subconscious knew he wasn’t the noble monarch he wanted to think of himself as, and everything fell apart on him through his own doing. (Which, by the way, was another epic Big Moment in the series. The heroes debate whether to take on an omnipotent, seemingly-benevolent Doom, and Cap says, “Is it even possible? If we decide to fight him, he might just annihilate us all with a bolt from the blue.” But ultimately, they decide he has to be stopped…and Doom just annihilates them all with a bolt from the blue. The next issue opens with Cap’s shield in pieces on the ground.)

And ultimately, Doom’s defeat provided the answer to the Beyonder’s question, for the audience if not the characters. Doom’s selfish desires were poisonous, and getting what he wanted–getting everything he ever wanted–worked out very badly for him, because he didn’t really know what he wanted and he wound up getting the wrong things. Self-knowledge matters more than power, and the ultimate “winner” is the Molecule Man, who learns that he’s always been able to do anything he ever wanted to do; he was just too scared to accept responsibility for that. And armed with that ultimate power, and even more importantly with that ultimate self-knowledge, the Molecule Man settles down to a little apartment in the suburbs with a nice girlfriend, content in the knowledge that fulfilling one’s desires doesn’t come from grabbing more, it comes from learning when you have enough. That’s a pretty deep message to come out of a toy tie-in series, but Shooter told it in a way that the average kid could understand.

Then, of course, the Beyonder came to visit the Molecule Man…but since this is “Things I Love About Comics”, we’ll stop there.

29

Aug

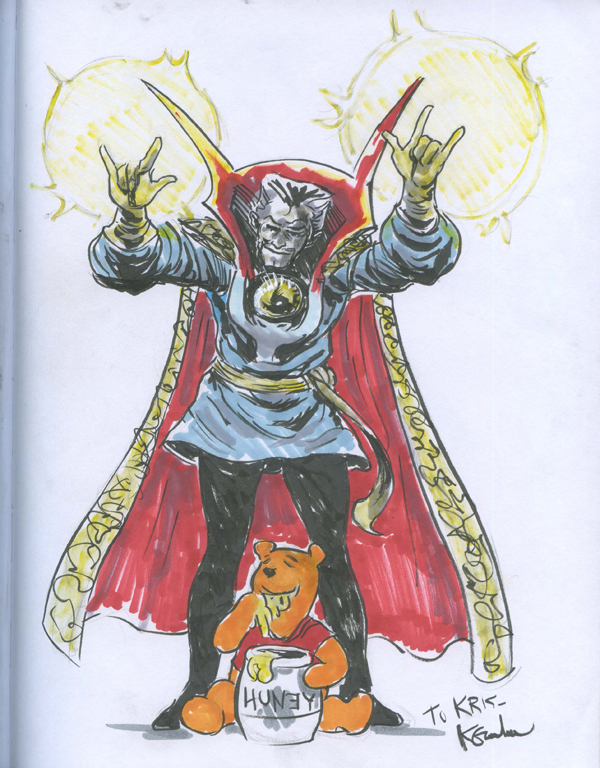

Yesterday was my favorite DC character other than Rex The Wonder Dog (who I need to start a new con sketchbook for, although the problem with Rex is that he is a dog and fairly easy to draw; any good Rex sketch, of course, has him doing appropriately Wonder Dog things, which means more complex drawings of Rex, say, disarming a nuclear bomb with his teeth while juggling baby kittens with his rearpaws, or as Rex calls it, “Tuesday”), so today of course is my favorite Marvel character:

Art by Keith Grachow.

continue reading "MGK’s Doctor Strange Convention Sketchbook"

28

Aug

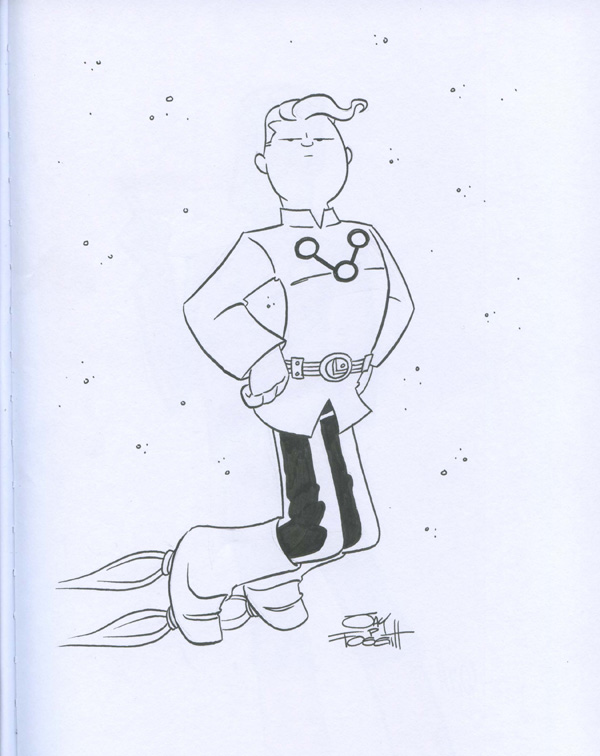

I am a big fan of dedicated-character convention sketchbooks, and last year – the first year I really had enough disposable income to start a proper con sketchbook – I decided to get a couple of dedicated-character sketchbooks going. These are taken from the first of my two sketchbooks, and it features one of my favoritest characters ever: Brainiac Five of the Legion of Super-Heroes.

So here are my collected Brainiac Five sketches, as of today:

continue reading "MGK’s Brainiac Five Convention Sketchbook"

27

Aug

My recap of Fan Expo is up at Torontoist.

In the next couple days I’m hoping to get up scans from my convention sketchbooks, because there are some goddamned awesome Brainiac 5s and Doctor Stranges out there. I think next year I’ll do a Rex the Wonder Dog sketchbook as well. (Of course, by next year I might be an exhibitor rather than press.)

26

Aug

My weekly TV column is up at Torontoist.

26

Aug

Click on thumb to see full

As always, you can also go to the dedicated Al’Rashad site.

23

Aug

Deltarno, in a comment on my ‘Defense of Onslaught’ post, asked what I thought of the Marvel titles these days. My honest answer is that I’m not really prepared to comment, because I don’t read Marvel anymore. It would be unfair of me to say, “The books all suck these days,” because I don’t really know what’s being published and who’s writing it beyond the stuff I hear on the Internet. And I’m not going to be That Guy. You know, the one who trashes loudly comics that he’s never read based on things he’s heard on the Internet.

That said, I’ve heard nothing that suggests to me that the problems that caused me to give up on Marvel (or DC, for that matter) have been resolved. They sound like they’re still obsessed with the metaplot at the expense of the quality of individual issues, they’re still crossover-happy to the point that you can’t follow a title like ‘Avengers’ or ‘X-Men’ without splashing out for a half-dozen books every month, they’re still so bound and determined to do psychological exploration of the damaged psyches of their characters that they’ve forgotten to make them sympathetic and likable, they’re still making story after story that’s about heroes fighting each other instead of villains, and they still seem to think that making a title “edgy” and “adult” always makes it better. (This still seems odd to me, because the audience for edgy, adult superhero comics seems to top out at about a hundred thousand or so, and the audience for superheroes in general seems to be in the tens of millions. But I’m not the editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics. Maybe he has information I don’t.) So I probably won’t go back, either, despite hearing good things from the host of this very blog about books like ‘Superior Spider-Man’.

But if you’re reading Marvel right now and enjoying it, then I’m happy for you. I want to be clear, this is not said in the passive-aggressive sense. The books aren’t for me, but if you’re the target audience and you’re having fun, then nobody should be telling you that you’re wrong to do so. I’m glad you’re deriving enjoyment from your hobby, because the only thing that would be really sad is if you weren’t and were still doing it anyway. I wasn’t, so I quit. I’m not mad about it–Marvel does not owe me a publishing output catered to my personal tastes. I don’t owe them my customer loyalty, either. It’s not something worth getting upset over, even if I do sometimes look over at what they’re doing and wonder, “What exactly is their business plan right now?” I can’t imagine going into a comics store, dropping twenty or thirty bucks a week on comics that do nothing but make me angry, and then getting onto the Internet to blog about how mad I am at Marvel for “making me buy” things I don’t enjoy. I don’t know whether people do that out of obligation, a sense of completism, or sheer bloody-minded stubbornness; but I can’t think of any reason that it would be Marvel’s fault if I kept spending money on a product I didn’t like. I’m just glad that someone’s enjoying all these comics, because they’re clearly not aimed at me.

Between the strange ape-skeleton monster, the complete lack of cooperation with spatial geography as we commonly understand it, and the inevitable death of your character, clearly Temple Run 2 is in fact secretly part of the Cthulhu mythos, and your intrepid adventurer is fleeing through the weird geography of an alternate dimension, completely unaware that they are no longer on Earth and that they can never return to it. Discuss amongst yourselves.

20

Aug

FLAPJACKS: So we have stars. Is this Star Trek? Or Star Wars?

MGK: I doubt it. If it was an established franchise this would make sure all the nerds knew it was an established franchise, right? There would be some ambiguity, but by the end of the trailer there would be an “oh that’s exciting” money shot.

FLAPJACKS: A tease-en-scene, if you will.

MGK: Very well done.

FLAPJACKS: I actually thought of it last month but now I get to use it.

MGK: Guy staggering through the surf.

FLAPJACKS: Maybe it’s Aquaman.

MGK: What did I just say about established franchises?

FLAPJACKS: I know, but I would counter with “nobody cares about Aquaman.”

MGK: …okay, fair point.

FLAPJACKS: Also, the guy is tied up, so that would make sense, right? Aquaman being exiled from his home planet.

MGK: Ocean.

FLAPJACKS: Whatever. He can breathe underwater so being tied up in the ocean, that’s no big deal. In fact he’s being driven to shore because that’s how underwater people execute criminals!

MGK: You’re saying that in Atlantis, beaching is a form of execution?

FLAPJACKS: Yes!

MGK: But why don’t the prisoners just walk back to the ocean?

FLAPJACKS: That’s why they tie them up! But Aquaman can breathe air, so he survives the beaching… and… um.

MGK: You didn’t have any idea as to what happens next, did you.

FLAPJACKS: Not really, no.

MGK: We call that “the Aquaman problem.”

FLAPJACKS: So. There’s also another guy with his lips sewn shut.

MGK: You know he’s probably evil because he has to drink his meals through a straw.

FLAPJACKS: …I have no idea what this is supposed to be.

MGK: You’re not supposed to. Remember when the Cloverfield teasers first came out and people were all “is this Godzilla? Is it a superhero movie?” because the idea of something new scared them, much like the dancing scared the rural people in Footloose.

FLAPJACKS: So in this metaphor I am the strict country preacher who doesn’t get today’s youth?

MGK: Pretty much.

FLAPJACKS: Dang.

19

Aug

Want to feel old? Hugh Jackman has been playing Wolverine for FOURTEEN YEARS.

Posted by MGK Published in The Internets, TVMy weekly TV column is up at Torontoist.

19

Aug

I’m going to need to lay a little groundwork for this one.

Back in the early Nineties, a group of superstar creators rose to prominence at Marvel. They practically reinvented storytelling in comics, breaking a lot of rules that the established writers, artists and editors at Marvel believed at the time were vitally important to telling good comic-book stories. Their art was, for the most part, totally different from the style that Neal Adams and Jim Aparo had popularized, and frequently broke rules of anatomy and perspective. Their stories shook up the established status quos of many series, introducing overt anti-heroes who grew to dominate the landscape of comics (like Cable and Venom, to name two quick examples.) The older guard of editors who ran the company didn’t really understand why these younger creators were popular; they didn’t even like the books they were publishing, in some cases. But they sold like hotcakes, they were incredibly popular with Marvel’s target audience, and the young men seemed to know what they were doing.

Then, almost literally overnight, the superstar creators all quit. Worse, they started their own competing company. To say that this caused some problems at Marvel would be a titanic understatement.

In essence, Image changed all the rules for what creators were allowed to do on a comic. Because Marvel’s editorial staff looked at the Image books and saw nothing but crap. Whether it actually was crap is almost irrelevant to the conversation; the point is that Marvel was put into the position of trying to emulate Image, and they patently did not understand what made Image books popular and held the comics in question in no small amount of contempt. To them, “make it more like Image” meant “make it louder and shittier.” And they proceeded to do just that. This is not to say that there were no good comics in the Nineties, but Marvel did make a lot of mistakes in their attempt to imitate the Image creators’ style, because they were deliberately trying to do bad comics in the mistaken belief that this is what their audience was into at that point.

I won’t go over the mistakes in detail, but I will mention enough to (hopefully) forestall people coming to the defense of these books. Ben Grimm wearing a giant metal bucket on his head because Wolverine had disfigured him. The Wasp as a literal insect woman with yellow skin and antennae. Teen Iron Man. The Clone Saga. X-Cutioner’s Song, a story with a denouement that is literally incomprehensible to modern readers because they were writing dialogue related to Cable and Stryfe’s origin without having actually agreed on what that was yet. The Legacy Virus, a plotline that managed to last six years without ever actually going anywhere. The Upstarts and the Gamesmaster, ditto. Sabretooth, the White Queen and Mystique all joining the X-Men within months of each other. Joseph, a Magneto clone who never had a point or a purpose beyond being in the series. X-Man, a spin-off book with no central concept and a character whose origins were a convoluted nightmare. Wolverine losing his adamantium claws and slowly mutating into a thing that looked like a feral weasel wearing a bandana over his head. Captain America wearing power armor. Force Works and Fantastic Force. The Crossing. Starblast. If you haven’t had enough yet, I could probably dredge up some more.

The point is, Marvel was at this point desperately flailing for a direction. They literally had no idea what would appeal to their audience, their creative vision was completely undercut by self-doubt, and they had made a number of major, seemingly irrevocable creative missteps. Onslaught, a character who they’d already introduced as the main villain behind their next crossover, was quite literally nobody–behind the scenes, the only decision that had been finalized was that they needed to follow up the Age of Apocalypse with something big, and they needed to start selling it right away before the people who’d been reading that crossover drifted away. There was no planning, no cohesion, no direction, nothing but throwing shit against the wall to see what stuck.

In that light, it’s amazing how well ‘Onslaught’ turned out.

‘Onslaught’, the storyline, probably wasn’t intended as a metaphor for the direction that the company had taken the last five years. For that matter, neither was Onslaught, the character. But it worked perfectly for that. Onslaught was the ultimate evolution of the pointless heel turns, the random and unmotivated shock plots, the endless raising of the stakes and the unearned “big moments”, all wrapped up in Liefeldian armor and given a life of its own. His whole origin was tied up in the biggest, most pointless, least comprehensible and most off-model moments in the post-Claremont era of the series, and when he finally broke free of Charles Xavier, his host, it felt strangely appropriate. It was as if everything bad about the Nineties had broken free and given itself flesh, and was stalking the Marvel Universe in an attempt to inflict its awful, poorly thought out paradigm shifts on every single character and series.

In that light, the character’s bastardized mess of an origin actually made sense, as did his shifting and incoherent goals. He was the living embodiment of everything bad about Nineties Marvel, of course he was going to be pointlessly convoluted and inconsistent! Again, I’m not saying that any of this was intended by the writers on the series or the crossovers, but it fit the metatextual concept of the series so well that it almost bleeds out of the cracks. When the heroes of the Marvel Universe finally defeat Onslaught, not through brutality or pointless violence but through nobility and self-sacrifice, it feels like they’re actually taking a stand for everything that superheroes are supposed to believe in. They’re saying, “No, this is what we’re about. Doing the right thing, no matter what the cost.”

And on that level, ‘Onslaught’ really did work. It was a Viking funeral for everything shitty about Nineties comics, wrapping up the X-Traitor plot and tying off the bloody stump of all the attempts to rewrite Xavier as a manipulative bastard. It ended by almost literally throwing all the crappy Nineties versions of the Avengers and the Fantastic Four onto a massive bonfire, burning away Teen Iron Man and the Malice Invisible Woman and the disfigured Thing and the what-the-fuck-was-that-even-about Thor and allowing us a full year of real time to forget it all like a bad dream. It allowed the Image creators to write Marvel’s flagship titles for a full year, just to show us all that they really had no idea what to do with any of them beyond simply aping other people’s ideas less well. (‘Heroes Reborn’ really was the point where Image ceased being taken seriously as a threat to Marvel and DC. They remained a solid company, and have gone on to do some really good work, but 1997 ended talk of the Image style being the new paradigm for comics.) The only thing that would have made it better was if Peter Parker and Ben Reilly had fallen into the ‘Heroes Reborn’ universe together, and come out as a single character.

And Marvel did some really interesting things around the edges of the ‘Heroes Reborn’ event. For a full year, they told stories in a Marvel Universe without the Avengers and the FF, and they seemed to actually be thinking about what that might mean instead of just using it as the starting point for another goddamn crossover. This was where the Thunderbolts started, for example. When they did bring back the Avengers and the FF, it was with some actual talent behind it, although Waid’s ‘Captain America’ and Busiek’s ‘Avengers’ and ‘Iron Man’ clearly worked better than Lobdell or Claremont’s ‘Fantastic Four’. The beginnings of Marvel’s resurgence under Quesada came in the wake of ‘Onslaught’. It didn’t all come at once; the X-books were still suffering from the deeper lack of direction caused by the departure of long-time writer Chris Claremont, a problem that wasn’t even solved when Claremont returned to the books a few years later. But in a lot of ways, the fever had broken.

‘Onslaught’ was everything we thought we wanted out of comics in 1996. If nothing else, it deserves credit for snapping us out of that.

19

Aug

Click on thumb to see full

As always, you can also go to the dedicated Al’Rashad site.

14

Aug

“I don’t know what we’re going to do.”

Van Deesen had been saying this, again and again, under his breath, for the last twenty minutes, and Lopez was frankly tired of it. This was the problem with rich kids, she thought. One real problem, one real problem, and they all go to pot.

Unfortunately Van Deesen had now turned to her. “What are we going to do? We can’t do anything,” he bleated at her. “We’re going to lose our jobs! If we’re lucky!”

She waved idly behind her at the holographic readout – a flatscreen would have done, really, but the station funders wanted a three-dimensional representation of all weather in what they were supposed to call “the Idyll” but which she always pronounced, in her head, as “Idle.” It impressed stockholders when they came by on tours to see the climanipulation team dramatically gesturing across the “sky” like they were the Hand of God and then imaging the accelerated-time result. (The gestures, frankly, were a pain and everybody just preferred to use buttons instead.)

The readout showed exactly what it should show: sun-dappled clouds, not so many clouds as to be threatening but enough that they would provide contrast in the sky and cut down on glare. In the eastern half, where the sun was beginning to set, the clouds were gathering more intensely. It was Thursday, and Thursday meant the twice-weekly heavy shower (for five hours, from 1 AM to 6 AM) that meant nobody had to water their lawn. It all looked perfectly normal.

“This isn’t normal!” God, but Van Deesen was giving her a headache. And of course he was right. Those clouds were gathering three hours ahead of schedule – three hours before they were even scheduled to flip many switches and commence the evening’s electrostatic cloudseeding, creating rain-on-demand, the type of rain the network’s customers demanded: as much as needed and nothing that interfered with their day-to-day business. This wasn’t even the four-times-yearly scheduled daylight rain (“Jump In Puddles! Dash Between Those Drops!”). No, this was unscheduled rain. And probably someone was going to get fired for it. Ideally, Van Deesen.

“Look, Sheldon, it’s pretty straightforward.” She shrugged. “Do you remember studying feedback theory in your climanipulation classes?” She went on before he would have a chance to start improvising an explanation as to why he didn’t. “It’s your classic Dessikan feedback loop. You can’t completely control weather; it’s too expensive a proposition -”

“Yeah, I know, hence the Idyll, where we can control it, and hence it costing extra to live here.” Van Deesen snapped off the words like someone who had never been outside the Idyll. Probably he never had. “But this isn’t being forced from the exterior. The nullification zone is empty all around the Idyll – twenty kilometers every way of nothing but clear skies.” Van Deesen’s voice was growing accusatory. Not towards her – that would be stupid even for him – but towards the weather. It was odd to realize that, but Lopez knew it to be true.

She sighed. “I’m not saying it’s being forced from the exterior. It doesn’t have to be, you know.” She said “exterior” almost neutrally and was proud of it. Nobody would know, looking at her, that she was a gushtown brat who grew up under a metal roof – a roof that was so loud from the constant pounding of rain that she could sleep through damn near anything nowadays. When her uncle had smuggled her into the Idyll at the age of nine, he’d had to take her to the doctors to get a cochlear matrix implanted in each ear; she had been damn near deafened. Her mother hadn’t been able to afford the good earplugs. “Go back and read your Dessikan. It’s pretty straightforward: he predicted that the inevitable result of atmospheric static manipulation was stratospheric collection of water vapour, which would eventually descend and create a superstorm. It’s pretty basic math. We all read it.”

Van Deesen rubbed his temples. “But it wasn’t supposed to happen for years! We’re going to get blamed, Kace! It doesn’t matter if we say it’s math, all that matters is the suits all thought it wasn’t going to happen for another twenty-two years. Who do you think they take it out on?”

Lopez shrugged again. It was amazing to her that Van Deesen hadn’t figured out the full ramifications of what was happening. “I think they’ll have more to worry about, frankly. Have you looked at where that storm is coalescing?” She tapped her oplet gently and the holographic display zoomed in. “I’m pretty sure that storm is going to take out the static wall generators in 7B, and when that happens… well.”

Van Deesen started freaking out at that point, but Lopez was no longer paying attention. She turned to the window and looked out at the perfect horizon, at the sun setting on exactly enough cloud cover to create dazzling pinks and scarlets (this was color arrangement 479, and like all the others it was copyrighted). It was glorious and it was bought and it was paid for, and she imagined how beyond it, over the horizon a hundred miles away, she could see in her mind the permanent storm that the people here had forced on everybody else (because after all who was going to make them pay for your weather?), held at bay by a long row of poles and towers emitting targeted static and plasma discharges, and how each of those poles was interdependent on the others, and how the generators weren’t ready to handle the ravages of a proper superstorm. How it all depended on the universal consent to have every day be beautiful. She wondered if any of them had ever considered what might happened if someone didn’t consent.

She thought about her mother’s face, completely smooth even into her late forties when she died of the pneumo, smooth like everybody’s faces were in the gushtowns because wrinkles simply wore away in the day-to-day. She wondered how Van Deesen’s face would look after a few years of rain, and how the suits would look after they realized this storm wasn’t a one-off occurrence but that in fact their remaining twenty-two years of profits were gone, had never really existed in the first place.

And as she looked out onto the horizon, she realized that she was thinking how good it would be to have weather just like she had done when she was a kid.

Search

"[O]ne of the funniest bloggers on the planet... I only wish he updated more."

-- Popcrunch.com

"By MightyGodKing, we mean sexiest blog in western civilization."

-- Jenn

Contact

MGKontributors

The Big Board

MGKlassics

Blogroll

- ‘Aqoul

- 4th Letter

- Andrew Wheeler

- Balloon Juice

- Basic Instructions

- Blog@Newsarama

- Cat and Girl

- Chris Butcher

- Colby File

- Comics Should Be Good!

- Creekside

- Dave’s Long Box

- Dead Things On Sticks

- Digby

- Enjoy Every Sandwich

- Ezra Klein

- Fafblog

- Galloping Beaver

- Garth Turner

- House To Astonish

- Howling Curmudgeons

- James Berardinelli

- John Seavey

- Journalista

- Kash Mansori

- Ken Levine

- Kevin Church

- Kevin Drum

- Kung Fu Monkey

- Lawyers, Guns and Money

- Leonard Pierce

- Letterboxd – Christopher Bird - Letterboxd – Christopher Bird

- Little Dee

- Mark Kleiman

- Marmaduke Explained

- My Blahg

- Nobody Scores!

- Norman Wilner

- Nunc Scio

- Obsidian Wings

- Occasional Superheroine

- Pajiba!

- Paul Wells

- Penny Arcade

- Perry Bible Fellowship

- Plastikgyrl

- POGGE

- Progressive Ruin

- sayitwithpie

- scans_daily

- Scary-Go-Round

- Scott Tribe

- Tangible.ca

- The Big Picture

- The Bloggess

- The Comics Reporter

- The Cunning Realist

- The ISB

- The Non-Adventures of Wonderella

- The Savage Critics

- The Superest

- The X-Axis

- Torontoist.com

- Very Good Taste

- We The Robots

- XKCD

- Yirmumah!

Donate

Archives

- August 2023

- May 2022

- January 2022

- May 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- June 2020

- March 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- February 2007

Tweet Machine

- No Tweets Available

Recent Posts

- Server maintenance for https

- CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards

- CALL FOR NOMINATIONS: The 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards (the Theszies)

- The 2020 RSPW Awards – RESULTS

- CALL FOR VOTES: the 2020 Theszies (rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards)

- CALL FOR NOMINATIONS: The 2020 Theszies (rec.sport.pro-wrestling awards)

- given today’s news

- If you can Schumacher it there you can Schumacher it anywhere

- The 2019 RSPW Awards – RESULTS

- CALL FOR VOTES – The 2019 RSPW Awards (The Theszies)

Recent Comments

- George Leonard in When Pogo Met Simple J. Malarkey

- Blob in How Jason Todd Went Wrong A Second Time

- Cindi Chesser in Thursday WHO'S WHO: The War Wheel

- Scott Hater in Bing, Bang, Bing, Fuck Off

- dan loz in Hey, remember how we talked a while a back about b…

- Sean in Server maintenance for https

- Ethan in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…

- wyrmsine in ALIGNMENT CHART! Search Engines

- Jeff in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…

- Greg in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…