Back when I did my post of the least essential Elseworlds, I had it in my head that I would eventually get around to doing the most essential Elseworlds. I tried a few stabs at the post, but kept running into the same problem, over and over again: even most of the best Elseworlds aren’t really essential.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t good Elseworlds. There are fun, pulpy adventures: JLA: Justice Riders, Superman: A Nation Divided, JLA: Age of Wonder, Batman/Houdini. There are thought experiments draped in superhero clothing, like Superman’s Metropolis or Red Son or Superman/Batman: Generations or World’s Funnest. There are Elseworlds which use alternate reality to tell stories almost entirely divorced from the meaning of the original characters, like Kal or JSA: The Liberty File. There are superhero epics that almost play more like a good issue of What If…? than as an Elseworld, like The Golden Age or JLA: The Nail.

All of these are good comics, and some of them are great ones (The Golden Age). But I hew to the idea that an alternate-reality story should, in some way, serve to illuminate the primary reality by shedding new light on the character. James Robinson’s revisions of the Golden Age characters in The Golden Age, while interesting, don’t really qualify. Superman: Speeding Bullets comes very close, by putting Superman in Batman’s shoes and using the familiar Batman story points to illustrate how Superman and Batman are totally different people and in fact could never be each other, but the third, redemptive act feels forced and unearned, in a “well it’s time for Superman to realize he’s still Superman” way. (It’s a story that needed to be longer, frankly.)

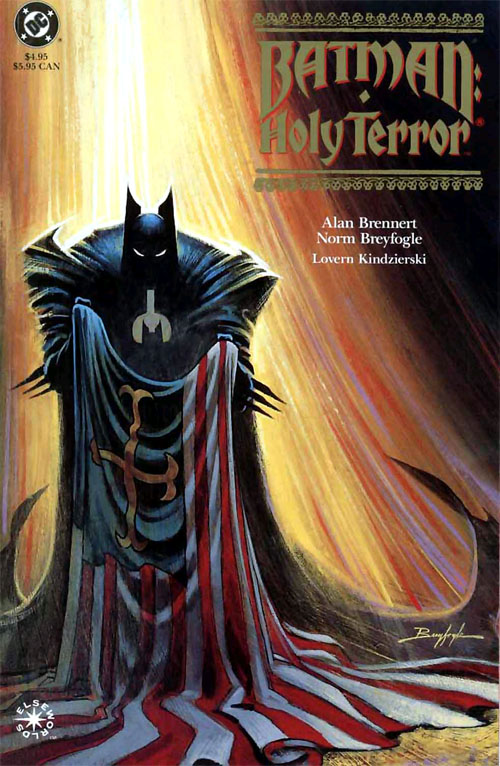

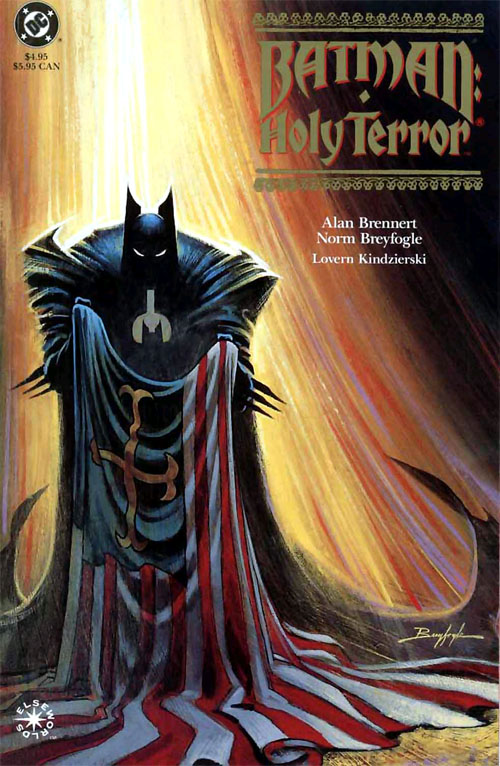

In the end, there’s really only one Elseworld that uses the alternate-reality trope to make a statement about the character it’s supposed to be about. Just one. But it’s one of the best Batman comics ever written, and of “the best Batman comics,” probably the least known.

Batman: Holy Terror isn’t just the best Elseworlds, it’s also really the first. I think its early nature is one of the reasons it’s so good; it avoids the formula later Elseworlds would eventually find themselves stuck within and just manages to be a compelling alternate-reality story because it dares to consider the fact that in an alternate reality, people make different choices.

In Holy Terror, the world is one where Oliver Cromwell survived the malaria that killed him in the “real” world and lived another decade, long enough to see the Protectorate he had established become firmly accepted. That’s a pretty bold premise, and Holy Terror doesn’t get caught up in explaining the 350 years of history in between then and now; it just sets out the current world, which is a theocratic American colonial portion of the Commonwealth.

In this world, Batman’s parents weren’t killed by a random criminal; they were killed by agents of the state for “seditious” medical behaviour (the comic never explicitly says that Thomas Wayne was, among other things, an abortionist, but it’s pretty clear that he was). Batman, instead of punishing crime, chooses to punish the unjust state. And that lets Alan Brennert make some pretty bold statements about superhero writing and Batman in a 64-page comic.

Firstly, Brennert asserts that superheroism as we know it is more or less explicitly tied to a free society. Costumed vigilantism doesn’t work in a security state. Of course, this is less revelatory a concept after Marvel’s entire output from Civil War through Siege more or less demonstrated, at length, why this was the case, but Holy Terror makes it far more explicit by asserting that superheroes are either troublemakers or assets to any dictatorial regime. Unpowered heroes are the former. Powered heroes are the latter, and they’re not simply assets for their abilities but for their very genetic stock, which is both horrific and rings a sinister-but-true note.

Secondly, Brennert explicitly makes Batman a terrorist in this. You can say that Batman is a heroic terrorist, certainly, but there’s simply no way that Batman, in this book, can be construed as anything but. (He even uses the word “jihad” to describe his struggle in his final speech.) That’s a very bold thing to say about Batman and one that, in later years, might not pass editorial muster.

Finally and most importantly, Brennert makes the case that Batman isn’t someone shaped by a traumatic incident, but someone reacting to the society which allowed that incident to happen. In this world, Bruce Wayne has all the resources that he does in the “real” world, but when his parents are killed, he doesn’t become Batman. He trains for it, but eventually abandons the calling to become a priest, and only resumes the idea of Batman when he learns that the state murdered his parents rather than a common criminal – and even then, he is plainly out for revenge rather than justice. Only when he finally realizes the full scope of what the theocratic state has become does he truly embrace the mantle.

This is a fascinating idea of what makes Batman be Batman, because it goes beyond the simple “parents shot -> fight crime forever” motif that most people start at. Most people, when they lose people in a traumatic criminal incident, do not decide to become a cape-wearing vigilante, even in the DC Universe, and Brennert suggests (and indeed explicitly says, in the final page of the comic) that Batman is really no different in this regard: what motivates Batman is not his loss, but the ongoing horror which causes that loss. In the “real” DCU, it’s crime and the continuing breakdown of society. In Holy Terror, it’s a tyrannical regime. This is a much more complex motivation for Batman than “parents dead,” and frankly it’s a superior one.

That’s why alternate reality stories can be truly great: they can take a different setting and use that setting to reveal more about the character’s inner self than might otherwise have previously been visible. Holy Terror is really the only Elseworld to do this so successfully; it’s why it’s the only one that is a must-read on that basis.

(And I just realized that I’ve managed to go through this entire post without mentioning Norm Breyfogle’s art once. Short short version: Breyfogle is, for me, the definitive Batman artist, and this comic is a superlative example of just why that’s the case.)