26

Jul

20

Jul

Not Quite Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

19

Jul

17

Jul

Reading MGK’s post about the recent resurrection of Kraven the Hunter reminds me of one of my core problems with superhero comics…not “comics these days”, not “Marvel Comics” or “DC Comics”, but one of those things that I always have to grit my teeth and ignore about the entire pulp-inspired genre of men and women with super-powers. And that’s the way that death and resurrection are treated so cavalierly. I’ve posted in the past on how it’s not just resurrection that’s the problem, but death itself: When death is common, resurrections have to be common or else you start running out of people to kill. This cheapens the sense of drama that death brings; how can you be worried that the main character might die if you know they’ll just be resurrected in five years?

But there have been some stories over the years where the death was intended to be permanent…and not just that, but the permanent death was used to craft a genuinely powerful and moving story about that character. Those stories deserve to be remembered, because it’s not their fault that someone decided later to bring the dead person back for a quick sales boost. So let’s talk about the truly great deaths, shall we?

5. Aunt May. I’m actually of the school that says Aunt May shouldn’t die, because despite the fact that her age and infirmity have almost become a running gag, she fulfills such a vital role in the Spider-Man storytelling engine that getting rid of her creates more problems than it solves. But if you have to kill her off, you’d have a hard time doing it better than in Amazing Spider-Man #400. This was exactly what her death needed to be–not at the hands of some super-villain or monster, but simply a gentle passage with her beloved nephew at her side. It was sweet, moving, and sad…even if her resurrection was probably necessary.

4. Supergirl/The Flash. I’m not really sure how much of this was actually the way they were written, and how much of it was just the sheer iconic majesty of their deaths as part of the universe-shattering Crisis on Infinite Earths. Of course, twenty-five years later, a generation of fan-turned-pro writers with meter-length hard-ons for the Silver Age has undone just about everything good about Crisis, and the deaths of Supergirl and the Flash are no exception. But at the time, Crisis genuinely felt epic because it wasn’t trying to be so self-consciously epic, and the deaths of Flash and Supergirl worked because they weren’t done just check off the “shocking death!” tick-boxes of that year’s crossovers.

3. Kraven the Hunter. The man who inspired the list. I actually think Kraven probably had a few good stories left in him when he died; strictly speaking, his death wasn’t “necessary”. But he was starting to become progressively more pathetic as time passed, and this story restored the menace and majesty to one of Lee and Ditko’s loopier creations. And even if it hadn’t ended with his death, it would have ended him as a character; once he defeated Spider-Man, what was left for him to do in the Spider-Man books? His suicide was somehow the least shocking element of the story, and the story was a masterful work of craft by some of the finest talents in comics.

2. Jean Grey. I’d argue that this one was a bit of a mistake, because Jean is such an iconic character in the X-books. But Claremont and Byrne didn’t plan to kill her to begin with, so I’ll give them a pass on that one…and they managed to turn the “problem” of killing Jean into one of the most dramatic scenes of sacrifice in Marvel history. The fact that it created years of hassles for later writers, who had to find a replacement for Jean, replace the replacement with Jean, and then merge Jean with her own replacement and then get rid of the replacement completely. (And then Grant Morrison made the indefensible mistake of killing Jean all over again, in a much less dramatic fashion for a much smaller pay-off. I loved Morrison’s run on X-Men, but he was edited way too lightly. Mark Powers should have recognized that Jean must have had some kind of value, or they wouldn’t have spent so much time and effort bringing her back in the first place. Throwing something away and finding out you need it later is an accident. Throwing something away, rooting through the trash to get it back, then throwing it away again later is just stupidity.)

1. Gwen Stacy and the Green Goblin. A triumph. A sheer, unmitigated triumph. The first half of the story has a wonderful atmosphere of gathering gloom, as what seems to be a standard rescue-the-hero’s-girlfriend story feels inexplicably ominous and ends not with a triumphant hero, but with Spider-Man cradling his girlfriend’s body and swearing murderous revenge on the villain. And unlike the other sixteen billion times that happens in a comics story, you felt a) like he really meant it and was going to do it, and b) genuinely unsettled. Spider-Man doesn’t kill. We all knew that. But we knew the Green Goblin really needed to die. The subsequent story elegantly resolved that with a death that felt like the universe was punishing the Goblin, like his death was karmic retribution for his act of callous murder. The surprisingly adult ending to the story, with Peter realizing that vengeance was hollow and MJ discovering a new maturity by comforting him in his grief, was the icing on the cake. This was a genuinely stunning, brilliant story, and it says a lot that not even self-avowed “Gwen was Peter’s One True Love” fanboy and editor-in-chief Joe Quesada has been able to bring Gwen back. (As for the Green Goblin…don’t even get me started. Bob Harras was a Philistine.)

As always, feel free to add your opinions in the comments!

16

Jul

So Amazing Spider-Man has been running a sort of overall-metaplot called “The Gauntlet” all year, where the heirs of Kraven basically beef up every one of Spidey’s villains and then send them after him (or manipulate them into doing so). Originally, the implication was that the Kraven family was trying to knock Spidey down enough to then take him on themselves, a la Bane’s plan for Batman in “Knightfall.” This didn’t entirely work in terms of the stories that were being told, mostly because the rotating-writer-and-weekly format of ASM doesn’t lead itself to the sort of cohesive storytelling you want for this sort of plot, so at the same time as Spidey was fighting villain after villain, he was also engaging in all his other running subplots, which meant that the “beat him down into exhaustion” idea didn’t really work.

This became obvious early on, so the ASM writers collectively shifted gears (or maybe they intended it all along, but I don’t really think it reads that way) and shifted the Kraven family’s focus so that they weren’t so much interested in defeating Spider-Man as they were in changing his nature to become a more primal nature-warrior (the “Spyder”, a nice callback to “Kraven’s Last Hunt”) that they could then defeat. This worked much better with the nature of the comics model they were using, and some of the various rogues’ gallery stories that came about as a result are just instant classics. The Lizard four-parter has already been hailed in other quarters, and deservedly so, but the Rhino and Sandman stories were only a step behind, and the Electro and Mysterio ones quite decent as well; the only failure was the Vulture one, and that wasn’t bad so much as it was just kind of there.1

And then, in the dramatic conclusion of this year-long metaplot, it turned out the entire reason for all of it was… to bring Kraven back from the dead.2 This earns a “wait, what?” for two reasons.

Firstly, there really isn’t any reason to bring Kraven back from the dead. His death story is a classic, so it’s not like bringing him back avenges a sin against comics. (Whatever that is.) Kraven, more than most villains, is a really dated concept to boot.3 His heirs fulfill the functional purpose for his existence; you don’t need Kraven when Kraven’s Son or Kraven’s Wife or Kraven’s Daughter can do everything he can do anyway. And Kraven isn’t someone who should come back, frankly, even considering that comics characters do it all the time, because let’s not forget the reason he’s dead is that he committed suicide. The Chameleon points out in the story itself that resurrecting a character who killed himself is kind of a stupid idea, and as always, when characters in the story are pointing out that the premise of the story is stupid, you’re not in a great place.

Secondly, if you’re going to resurrect somebody with magic, you shouldn’t be doing it in Amazing Spider-Man, because Spider-Man’s world isn’t one where people magically come back to life (stupid deals with the devil aside); he’s not that sort of high adventure superhero comic. Spidey is street-level superheroics, even when he gets a little mystical. Spider-Man’s world is one where when you die, you’re dead: see Captain Stacy, Gwen Stacy, Jean DeWolff, the Tarantula, et cetera. If somebody gets killed in a Spider-Man comic and you want to bring them back, you need to establish that they were never really killed in the first place: see Norman Osborn, Aunt May or MJ, all of whom were thought dead at one point or another, but who were after-the-fact revealed to be not dead and Spidey just tricked.

However, there’s no way to use that method to bring back Kraven, since there is no way to write it so that Kraven didn’t really blow his head off. So instead, there’s another boring story about magic in a comic where it doesn’t really belong, and the resolution is that Kraven goes to the Savage Land until some other writer thinks of something to do with him, which – why would you go to all the trouble of resurrecting somebody like this if you don’t have a plan to do something with him? It’s a shame because most everything leading up to the reveal was really good, but the denouement was just unfortunate across-the-board.

- Why do all the other classic villains get a revamp or a pump-up, and Adrian Toomes gets pushed off to the side for a newer, freakier Vulture? The Rhino story was good because the newer, meaner Rhino got absolutely destroyed by the old one, making it clear that the original was the badass. Why no love for the original Vulture? [↩]

- I know there are some people who are all offended about Kaine and Mattie Franklin and Madame Web being killed off, but honestly, who the hell cares about them? [↩]

- Remember: he’s a big game hunter turned baddie. A big game hunter. Do they even exist any more? [↩]

12

Jul

10

Jul

Sometimes, you write a post to express an opinion…and sometimes, you write a post to discover one. Today’s post is going to be the latter, as I ruminate on the phenomenon that is Rob Liefeld.

For those of you who missed the 90s in comics…get down on your knees and give thanks to a merciful and just God. No, wait. That’s probably a little harsh. Seriously, for those of you who missed the 90s in comics, Rob Liefeld was one of the bona fide superstars of the medium. He began as an artist, hit it big with a stint on ‘New Mutants’, and went on to both write and draw its successor title, ‘X-Force’. Then he and a number of other major writer/artists split off from Marvel to form Image Comics, and Rob proceeded to start his own art studio where a number of Liefeld-influenced artists produced a large number of super-hero books. Eventually, after a falling out with his Image cohorts, Rob’s career kind of imploded; he’s still around and still working, but is nowhere near the phenom he was.

To a lot of people, this is cheery and heartwarming news. Nobody seems to be able to engender the kind of sheer hatred that Rob Liefeld does in the comics industry; mere mention of his name can induce apoplectic fits in certain fan circles. Fans complain that his writing is hackneyed, cliched, and derivative to the point of plagarism (when he’s got an aquatic super-hero whose name is “Namor” spelled backwards, it’s kind of hard to defend him on that count), and that his art is little more than chicken scratches with no grasp of anatomy, perspective, and no skill whatsoever.

And I don’t disagree with that assessment. I’ve heard all the stories–how he turned in pencil art that ended at the wrists and ankles, forcing an inker to fill in the hands and feet. I’ve seen his artwork, and there’s no question, it doesn’t match up with any kind of human anatomy. Women have breasts like they’re wearing a loose-fitting shirt with bowling balls dumped down it, guys have biceps bigger than their head, and everyone has about a billion teeth. It is anything but realistic.

But here’s the thing: Have you looked at Bill Sienkiewicz’s art lately? He left realism behind about thirty years ago, and fans love him for it. His art is deliberately abstract, conveying an emotional reality rather than strict photorealism, and he has more fans than he ever did when he was a Neal Adams clone. For that matter, take Vincent van Gogh. He never painted realistically, and in fact became more expressionist as he went on. Is his art bad because it doesn’t look like a photo?

But of course, Sienkiewicz did start out as a Neal Adams clone. He demonstrated that he could master perspective, anatomy, and a crisp “Silver Age” artistic style, and then branched out into his current style because it was the one he wanted to use. Perhaps that’s why he’s praised while Liefeld is pilloried; he showed that he knew how to draw first, while Liefeld never did.

Or perhaps it’s that the emotional reality Liefeld constructs seems to be one so utterly rooted in the realm of the sixteen-year-old boy. His characters are all hypermasculine uber-men with giant shoulderpads and guns bigger than their torsos. Maybe once you pass a certain age, that just starts to seem like arrested adolescence instead of an artistic style. Maybe Liefeld’s audience outgrew him.

Or maybe he just really was terrible, and it’s true that you can’t fool all of the people all of the time. I really don’t know, which is why I tend to stay quiet when people are slamming Liefeld. Because it’s possible…not likely, but just possible…that in a hundred years or so, he’ll be having the last laugh.

8

Jul

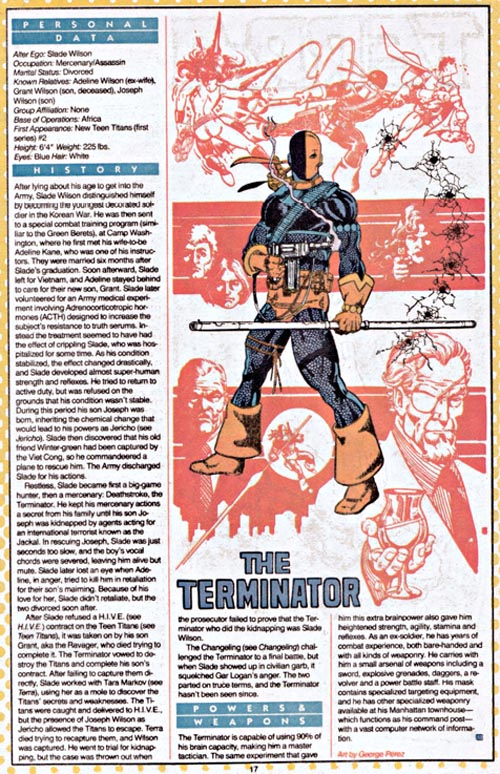

Hey, do you remember when you liked Deathstroke? I do. He showed up every once in a while, was incomparably badass, and then disappeared for a bit. And that was good. Why can’t we have that?

After all, Deathstroke’s core concept is one that doesn’t really lend itself to extended storytelling (which is one of the reasons his series was so lackluster, run for 65 issues though it did). He’s an ultracompetent mercenary. Up until about five or six years ago Deathstroke didn’t really want anything in the sense of having a grand purpose in life; he was just a guy who did his (extremely violent) thing for a lot of money, and that was basically enough for him. A character like this is reactionary at best: he doesn’t start or initiate plots because he doesn’t really feel the need to bother doing things like that, but he’s got enough substance that he’s not just a boring device either. Sure, Baddie With His Own Distinct Moral Code is a well-worn suit at this point, but it still works well enough that Deathstroke can be more than a gun on legs; he can be an antagonist with the ability to shift to ally when necessary. And that’s fine. He shows up every so often, beats the shit out of somebody, and fades back into the shadows in his costume which shouldn’t work but somehow does nonetheless.

About five or six years ago, though, Deathstroke got promoted, for reasons I will never quite understand (although somebody probably said “hey he’s awesome, let’s use him more than ever”). Now Deathstroke is one of the movers and shakers in the DC underworld, for reasons nobody really ever explained. I mean, it’s not like he likes any of the other villains or feels cameraderie with them; his sense of superiority, if nothing else, has remained intact. But now, rather than just being an ultracompetent mercenary, he’s been turned into an evil equivalent of Batman. He’s always three steps ahead, he’s always got two or three plans in motion, he’s of course completely deadly and able to beat up Green Lanterns and Flashes whenever he wants even if it doesn’t make sense (and fetishizing the “perfect human” concept is so much a Batman thing it doesn’t even need to be said, really).

But he’s not just evil Batman, because in his near-constant exposure since he got shoved up the ranks, he’s demonstrated that he’s actually an insane supervillain in the old-school style. Leadership in the Secret Society. Multiple plots to destroy the Teen Titans. A yearlong feud with Green Arrow (which he managed to lose, because Green Arrow decided to become a swordmaster in three months or something stupid like that). Most of it has been very stupid, and a lot of it has been retconned by writers to try and make it work with the “old” model for Deathstroke by saying that he only did all this shit to make his surviving children stronger, which smacks of desperation. (This assumes that anybody wants Jericho to be stronger. Jericho’s best moment, before he came back, was when he was an insane supervillain and Deathstroke stabbed him to death. Why don’t they do that again? Really, it’s the only argument for bringing Jericho and his whiteboy afro back: it’s so good seeing him get run through with a sword.)

And, of course, now he has his own villain team (well, another one), and he’s killed Ryan Choi for some reason, and Arsenal (ugh) will be on it. And of course, once again he’s got an extended master plan. Why does he have an extended master plan? Why does he need one? He’s rich and can do whatever the fuck he wants. Why does he have to be more overexposed than the fucking Joker? DC cancelled his series for a reason: he’s not a good protagonist. Why give him another one and stuff it with reject characters nobody cares about – I’m looking at you, new Tattooed Man – so we can get what will either be a terrible story arc that makes no sense or rendition #485 of “I have to do terrible things to test my children/make sure my children are safe”? Why not just let him sit in the background for a year or two and then let him come back and kick some ass for a brief period and have everybody be all WHOA?

(Ironically, his recent use in Batman and Robin made total sense and worked with the traditional version of the character; it’s very Deathstroke to take a job to fight Dick Grayson just because.)

7

Jul

Not Quite Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

5

Jul

2

Jul

Readers may be aware that I am a big fan of Doctor Strange, and since people are aware of this I frequently am asked of what I thought of Mark Waid’s Strange mini (okay, but just serves to underscore stupidity of the Brother Voodoo thing) or Rick Remender’s Doctor Voodoo series (joyless slog that seemed almost to want to kill the idea before even giving it a chance, not that this bothered me) or the recent Spider-Man: Fever mini that featured the Doc (unfortunate lack of Howard Hesseman).

So, to save people the trouble this time: The Mystic Hands of Dr. Strange, the latest in Marvel’s oversized black-and-white 70s-themed comics, is probably the best so far (and I thought Indomitable Iron Man was pretty great). Kieron Gillen and Fraser Irving’s main story is pretty much “How I Think Doctor Strange Should Be Written,” mostly, and the backups (a nifty Peter Milligan/Frank Brunner homage to Gene Colan-era Strange, and an experimental piece by Ted McKeever which underscores that Strange could, if someone so wished, be Marvel’s answer to Sandman in terms of more experimental approaches to traditional comics fiction) are just great stuff. The prose short story by Mike Carey is mostly a nice try, but then all of the prose stories in these B&W specials are nice tries, so no loss there.

Pick it up. (And get Indomitable Iron Man while you’re at it; it’s very good too, and I’d like to see Marvel continue experimenting in this format.)

28

Jun

25

Jun

Dan! Dan! He’s Our Boy! If He Can’t Draw It, No One… Will

Posted by Jaime Weinman Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), ComicsI picked up IDW’s first Archie Comics collection, The Best of Dan DeCarlo Volume 1. Since no one has yet posted a list of the contents, I thought I’d have a go at it.

Before I do, I’ll give some brief thoughts: the biggest quibble is that there are only 26 stories here, and they barely scratch the surface of DeCarlo’s output in the years 1958-1969. It’s limited to Betty and Veronica stories (DeCarlo had that almost exclusively, but also contributed to many other titles), and while almost all of them are good, not all of them can really be called standouts. However, I’m assuming that the choice of stories was dictated in part by which stories had original art available. Many of these stories look lovely, especially the late ’50s/early ’60s material when DeCarlo was at his best, and a comparison with an old copy of one of the comics seems to suggest that they’ve done a good job of reproducing the original colours.

The most pleasing thing, as I said elsewhere, is that the table of contents includes credits for all the stories, which originally appeared uncredited. DeCarlo got to sign his name alongside Stan Lee’s when he was at Marvel, doing Millie the Model, but at Archie he never got credit for anything except a tiny “By Dan n’ Dick” credit on some of the Josie comics. (Dick being the editor, Richard Goldwater.) That restores credit not only for DeCarlo, but for his main inker, Rudy Lapick, for his brother Vince DeCarlo, who did most of the letters, and above all Frank Doyle, who is credited here with writing 23 of the 26 stories — and the story for which the credit reads “writer unknown” might also be a Doyle script.

I’ve always been a fan of Doyle ever since I read his credited work in the ’80s, but his earlier, uncredited work is even better; it’s his writing that really elevates the best of these stories. DeCarlo is excellent here, sexy and funny and smooth, though by the end of the volume you can see how his slickness and polish sort of settled into a “factory” style (the early stories have much livelier and funnier drawing). But his drawing for Archie wasn’t any better than his work for Timely/Marvel, and if you want to argue that Millie the Model represents his very best drawing, I wouldn’t really disagree. But though Stan Lee’s writing on the Marvel/Timely humor titles certainly wasn’t bad, Doyle’s best stuff is in a different league (from Lee’s humour comics, I said — I’m not talking about the action/superhero stuff), with simple yet smart dialogue that’s not on-the-nose awkward like most comic book dialogue, a storytelling style that favours observational humour over plot mechanics, and lots of visual opportunities for DeCarlo.

I’ve compared Doyle’s work to “Seinfeld” because, on a smaller scale, he has that ability to build stories around tiny details of social life and relationships, or the way people can get obsessed with petty things. (That’s why the stories sound pretty basic when I summarize them, but have a much stronger profile when you read them.) The definitive story in the book, “Snob Sister,” is just five pages of Veronica showing Betty the different ways in which people can be “snobbish.” It’s simple, it’s fun, and it just comes off as a little smarter and sharper than any of the Archie imitators of the era.

So yes, there are a bunch of stories I would have liked to see in this volume that aren’t there. And fans of “good girl” art may be a bit disappointed that there are so few beach stories. But if you’re not a buff on this kind of comic, it’s a reasonably-priced introduction to DeCarlo’s art and the “good” years of Archie comics in general. And the decision to include credits is, as I said, something that fills me with a lot of good will. IDW has further Archie collections planned, including Bob Montana’s newspaper strip — which is where the Archie “house style” was really created — and a “Best of Stan Goldberg” collection with Stan Lee writing the foreword (this volume doesn’t have a foreword). I hope this one sells enough to justify more artist-themed collections and, in time, perhaps more DeCarlo collections; we really need a collection of his best post-Marvel work, the early, funny, pre-Pussycats Josie.

Here then are the contents. All scripts are by Frank Doyle unless otherwise noted:

1. “Birth of a Notion” (Betty and Veronica # 37, July 1958) – The boys toss around a doll and fool the girls into thinking they’re tossing around a baby. (Script: Sy Reit)

2. “Flip Flopped” (Betty and Veronica # 38, September 1958) – Veronica signs up for the cheerleading squad.

3. “Sheep Skinned” (Betty and Veronica # 44, August 1959) – The boys accuse the girls of being “sheep” for following the latest fashions.

4. “A Choice Choice” (Betty and Veronica Annual # 8, 1960) – Archie has to break his date with Veronica to take his mother out on her birthday.

5. “Something to Remember” (Betty and Veronica # 63, March 1961) – Veronica is peeved because Archie can never remember what she wears.

6. “The Reader Knows Best” (Betty and Veronica # 63) – Archie tries to do the same task for both Betty and Veronica, while assuring the reader that he knows what he’s doing.

7. “The Bluest Angel” (Betty and Veronica # 63) – Betty feels guilty about exploiting a misunderstanding between Archie and Veronica.

8. “Gambler’s Luck” (Betty and Veronica # 65, May 1961) – The girls toss a coin to see who gets Archie.

9. “Snob Sister” (Betty and Veronica # 69, September 1961) – Veronica argues that everyone is a snob about something or other.

10. “Switchcraft” (Betty and Veronica # 69) – Veronica thanks Betty for taking Archie off her hands.

11. “The Original” (Betty and Veronica # 77, May 1962) – Veronica explains that she doesn’t wear real jewels in public. (Credit reads “Writer unknown,” though it might also be Doyle)

12. “Commercial Caper” (Betty and Veronica # 83, November 1962) – Betty blows up “Archie Loves Betty” balloons.

13. “Glad To Help” (Betty and Veronica # 86, February 1963) – Archie tries to use Betty to make Veronica jealous.

14. “Dear Diary” (Archie Giant Series # 23, September 1963) – Betty writes her version of the day’s events in her diary.

15. “Sugar Doll” (Betty and Veronica # 103, July 1964) – Veronica tries to make candy.

16. “Heat Wave” (Betty and Veronica # 106, October 1964) – Archie, Betty and Veronica spend a hot day squirting each other with hoses.

17. “Bully Girl” (Betty and Veronica # 106) – Veronica shows off her new martial arts skills by beating up everyone in sight.

18. “The Midas Mess” (Betty and Veronica # 112, April 1965) – Everything Betty touches turns to gold.

19. “Prize Package” (Betty and Veronica # 112) – Betty tells Archie he’s won a “most popular boy” contest.

20. “Message Center” (Betty and Veronica # 116, August 1965) – Betty sees a message on the bulletin board saying Miss Grundy wants to see her after school.

21. “The Phenomenon” (Betty and Veronica # 117, September 1965) – Betty and Archie discover that when Veronica stands on her head, her speech balloons are upside down.

22. “Rhyme Time” (Betty and Veronica # 119, November 1965) – The narrator re-introduces us to the Archie gang, in rhyme.

23. “Do No Evil” (reprinted in Archie Giant Series # 137, January 1966 — but from the look of it it’s clearly an earlier story, probably from 1960 or so) – After the girls accuse them of being slobs, Archie and Reggie try to get revenge.

24. “Feed Deed” (Betty and Veronica # 130, October 1966) – At the beach, Veronica tries to outdo Betty’s cooking. (Script: George Gladir)

25. “Wing It” (Betty and Veronica # 155, November 1968) – Betty impresses the boys with her great throwing arm.

26. “Drive To Distraction” (Betty and Veronica # 167, November 1969) – Archie uses a beach umbrella to give Veronica some shade in his car.

23

Jun

Not Quite Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

Search

"[O]ne of the funniest bloggers on the planet... I only wish he updated more."

-- Popcrunch.com

"By MightyGodKing, we mean sexiest blog in western civilization."

-- Jenn

Contact

MGKontributors

The Big Board

MGKlassics

Blogroll

- ‘Aqoul

- 4th Letter

- Andrew Wheeler

- Balloon Juice

- Basic Instructions

- Blog@Newsarama

- Cat and Girl

- Chris Butcher

- Colby File

- Comics Should Be Good!

- Creekside

- Dave’s Long Box

- Dead Things On Sticks

- Digby

- Enjoy Every Sandwich

- Ezra Klein

- Fafblog

- Galloping Beaver

- Garth Turner

- House To Astonish

- Howling Curmudgeons

- James Berardinelli

- John Seavey

- Journalista

- Kash Mansori

- Ken Levine

- Kevin Church

- Kevin Drum

- Kung Fu Monkey

- Lawyers, Guns and Money

- Leonard Pierce

- Letterboxd – Christopher Bird - Letterboxd – Christopher Bird

- Little Dee

- Mark Kleiman

- Marmaduke Explained

- My Blahg

- Nobody Scores!

- Norman Wilner

- Nunc Scio

- Obsidian Wings

- Occasional Superheroine

- Pajiba!

- Paul Wells

- Penny Arcade

- Perry Bible Fellowship

- Plastikgyrl

- POGGE

- Progressive Ruin

- sayitwithpie

- scans_daily

- Scary-Go-Round

- Scott Tribe

- Tangible.ca

- The Big Picture

- The Bloggess

- The Comics Reporter

- The Cunning Realist

- The ISB

- The Non-Adventures of Wonderella

- The Savage Critics

- The Superest

- The X-Axis

- Torontoist.com

- Very Good Taste

- We The Robots

- XKCD

- Yirmumah!

Donate

Archives

- August 2023

- May 2022

- January 2022

- May 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- June 2020

- March 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- February 2007

Tweet Machine

- No Tweets Available

Recent Posts

- Server maintenance for https

- CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards

- CALL FOR NOMINATIONS: The 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards (the Theszies)

- The 2020 RSPW Awards – RESULTS

- CALL FOR VOTES: the 2020 Theszies (rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards)

- CALL FOR NOMINATIONS: The 2020 Theszies (rec.sport.pro-wrestling awards)

- given today’s news

- If you can Schumacher it there you can Schumacher it anywhere

- The 2019 RSPW Awards – RESULTS

- CALL FOR VOTES – The 2019 RSPW Awards (The Theszies)

Recent Comments

- George Leonard in When Pogo Met Simple J. Malarkey

- Blob in How Jason Todd Went Wrong A Second Time

- Cindi Chesser in Thursday WHO'S WHO: The War Wheel

- Scott Hater in Bing, Bang, Bing, Fuck Off

- dan loz in Hey, remember how we talked a while a back about b…

- Sean in Server maintenance for https

- Ethan in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…

- wyrmsine in ALIGNMENT CHART! Search Engines

- Jeff in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…

- Greg in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…