2

Mar

1

Mar

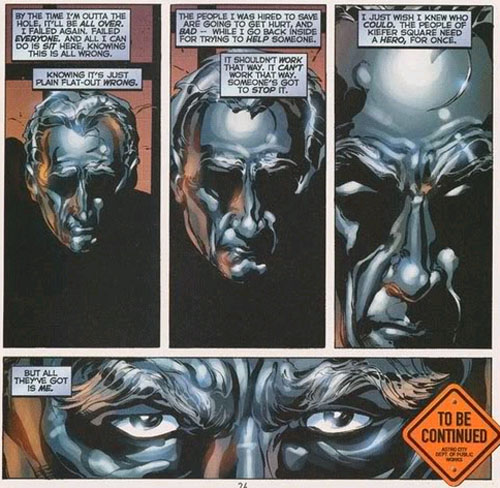

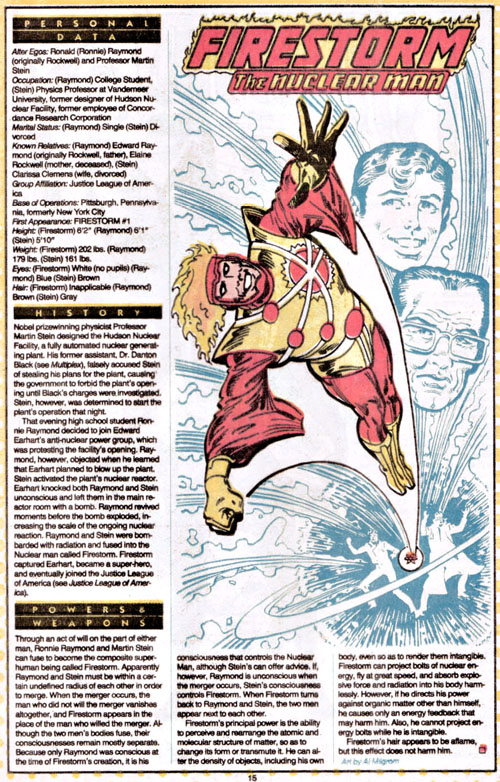

I’m currently in overdrive studying for my bar exams, so posting here is going to be a bit more perfunctory than usual and consist primarily of bits from comics I think are cool for the next couple of weeks.

28

Feb

23

Feb

Will Huston recently wrote me an email asking me to write about the appeal of Superman:

You’ve already done insightful pieces on Lois Lane and Lex Luthor, but I need something to sell people on reading Superman. A lot of my friends think he’s boring, or overpowered, which I don’t get, but I’m having trouble articulating my argument.

The appeal of Superman is quite simple and one that is frequently misunderstood by most people because they automatically want to turn him into a Jesus analogue. Admittedly, the reasons for Superman being cast in people’s minds as a Jesus analogue are pretty obvious and straightforward: the combination of godly power1 with a seemingly bottomless well of compassion and grace. It’s something that just hits the switch in our literary-critic mode that says “hey! Jesus!”

And it’s wrong beyond the most obvious and superficial level. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t see use; of course it does. But it’s still far too simple to really do the character justice.

Superman isn’t a Jesus analogue because, unlike Jesus, his moral vision is not imposed. The word of Jesus is the word of God2 and therefore what he says goes, dictation straight from the Almighty. Superman is the exact opposite: a man whose moral vision comes not from a source exterior to humanity but from humanity itself, via Ma and Pa Kent, who are themselves immensely decent people. He ultimately isn’t a received savior, regardless of the origin of his powers; he’s Superman, the apotheosis of what human virtue can be. He’s an aspirational figure first and foremost.3 There’s a reason people get S-symbol tattoos; they have meaning in a way that other superhero images just don’t.

But that’s only the surface of why Superman is a compelling figure and an engaging source of story. See, once you get past him being the aspirational figure that he is, you have to start wondering how and why he is that figure, what it means to be. People like to talk about how villains are more interesting, but with rare exceptions (like Lex Luthor), they really aren’t – they’re a base desire manifested in human form without the usual limitation we expect, an inversion of the norms. Similarly most heroes are just confirmation of those norms. Geoff Johns’ reimagining of Barry Allen as someone who became a cop because his mother died is a good example, framing virtue in simple cause-and-effect terms that are ultimately kind of limiting. DC has gradually introduced backstories explaining why most of their characters are superheroes, usually framing it in this manner. Hawkman is a superhero because of an ancient curse. Green Lantern is a superhero because his father died when he was little. Batman – duh. And so forth. You can call it the Batmanification of superheroes or the Marvelization – since Marvel’s characters often fall into superheroism by accident or happenstance when you consider their origins, which is often limiting in an entirely different way – but it is creeping and increasingly omnipresent in superhero storytelling.

Not so with Superman. Superman isn’t Superman because of some tragedy which informed his growth. Pa Kent does not die because of a failure on Clark’s part – indeed in most versions of the story, Pa dies when Clark is already Superman.4 Clark’s knowledge of Krypton doesn’t make him a superhero either; again, this is something he finds out later, too late to traumatize him. Clark is Superman because he decides to be Superman without being prompted. That’s more complex and nuanced a story than “somebody did something to me.” Superman’s story, which informs his entire character, is one of someone who chooses to be good of his own free will and agency, with no influence other than moral upbringing. That’s both more compelling than the “somebody did something to me” origin most superheroes have and more difficult to work with.56

The better class of Superman Elseworlds tend to bear this out. As I said a while ago, Red Son doesn’t quite work for me as a story, but it does help show what Superman would be without that wellspring of grace.7 Speeding Bullets similarly demonstrates – and fairly eloquently at that – how Superman simply isn’t right as a bog-standard wronged vigilante.

That, for me, is what is ultimately compelling about the character. I accept that not everybody will agree with me and that some will consider Superman’s moral strength a source of boredom rather than interest – and to be fair, when he’s written poorly it is boring, since his morality can become trite or boring in untalented hands, or worse a writer can simply get it dramatically wrong.89 But in a good story, I personally think Superman’s morality doesn’t make him dull; I think it makes him be what we all strive for, or should.

And indeed, the point of Superman in a way is that he never stops striving to be that thing either; his morality isn’t something innate, but something he actively works to be. To quote from Tom de Haven’s It’s Superman! (a novel, incidentally, that you should read):

Somehow he got here. Somehow he did. And somehow Lois Lane got here, too. She has the loveliest eyes he will ever see and he wants to see those eyes every single day, forever. And if she won’t love him, love him, he will still love her, love her all the more. And because he will – he will go on out and do the best he can, like everybody else.

Just like everybody else.

- Whatever Superman’s origin might be, for all intents and purposes he is a godly being and that’s all that matters. [↩]

- This is by way of being analysis, not declaration, but you probably guessed that already. But if you didn’t, there you go. [↩]

- Consider the ending of The Iron Giant. [↩]

- Or at least Superboy. [↩]

- The other major superhero who doesn’t fall into the “somebody did something to me” well is Spider-Man, who’s ultimately a superhero because of something he did to himself. See? There’s a reason he’s the most important character at Marvel. [↩]

- Also, Dr. Strange, although he’s arguably not major. [↩]

- Not that this was new, as Evil Superman, or Non-Virtuous Superman at least, is not a new idea and has not been for a very long time, but anyway. [↩]

- See Straczynski, J. Michael. Which is a shame, because the idea of Superman undergoing a morality crisis after basically having a traumatic breakdown is not a bad one in and of itself, but “Grounded” was just executed so poorly that I think future writers will avoid the idea. [↩]

- See also JLA: Act of God, wherein when Superman loses his powers it takes three issues of him moping like a loser to get over it and become a fireman – which, no, if Superman lost his powers he’d just shrug, accept it and move on, doing the best he can, because that’s who he is. [↩]

21

Feb

18

Feb

Posit the first: the Guardians of the Universe are the super-evolved descendants of the Smurfs, who existed in the universe prior to the current DC Universe.

vs.

Posit the second: the Smurfs are evolutionary offshoots of the Guardians of the Universe, much like the Controllers or Zamarons, who eventually forgot their history.

DISCUSS.

17

Feb

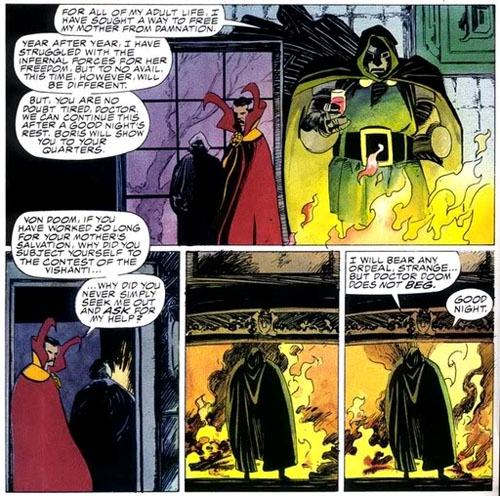

Firestorm suffers from a unique problem in comics, which is that he’s too powerful.

This is actually a rare thing to have happen. People complain that Superman is too powerful, but Superman gets an out because he’s Superman and his stories are often about the problems of being that powerful, particularly in relation to his friends and family, who aren’t.

But Firestorm is actually more powerful than Superman in a lot of ways. He doesn’t have the strength, but he’s pretty tough (and can turn intangible and doesn’t need to breathe and can absorb energy blasts); he’s got blasty powers and he can transmute matter at will (the “no organic matter” clause has been revoked, I think, three times now). This last one, as I have argued previously, makes him basically a godlike being. Which is fine, because superheroes can be that thing –

– but not all of them. And this is Firestorm’s problem: he is redundant, because he is designed to occupy the Superman slot in a universe where Superman already exists. Recall – as a way of demonstrating how this is the case – that in Superman Forever one of the Superman-analogues who comes along on the adventure is an alternate-universe Captain Atom who is basically a less immature Firestorm with a different costume.

It’s not an accident that all of Firestorm’s best character moments tend to come in stories where the really big guns have been taken out and he’s the only one left (JLA: Obsidian Age) or where the stakes are so big that Firestorm’s insane power level just makes him one of half-a-dozen godlike beings necessary to save the planet. (Crisis On Infinite Earths is the exemplar of this story type – and probably Firestorm’s best moment as a character, since in that story he basically becomes the Spider-Man of the godlike superhero set and gets most of the really good lines. I think this, along with some of the early 80s Justice Leagues where the JLA was fighting really high-stakes battles, are the best comics Firestorm has ever been in – and his character in them also informed the later early development of Kyle Rayner as a character. But I digress.)

The other way out of the “too powerful” trap is to up the scale and use the character in cosmic stories – see Green Lantern or Thor, for example. But Firestorm isn’t any good for this because he’s too grounded, because Firestorm’s weakness is that he’s too stupid to use his powers effectively, because understanding the elemental composition of matter is actually tricky. (At least, this is the case of the Ronnie Raymond incarnation, who seems to be the pre-eminent version of the character – even though I would argue the Jason Rusch version is superior.) It’s the sort of weakness that’s simultaneously a really clever idea and a really bad idea, since it’s original but also keeps Firestorm out of truly cosmic stories (because he’s a dummy) and instead fighting useless twats like these.

At this point I think the character is effectively mired in the dogshit he’s stuck in and needs a radical story revamp in order to be usable for the future, but that’s me. Shame. It’s an excellent costume.

15

Feb

Surely It Can’t Be Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

14

Feb

The Continuing Adventures of El Tyrano Magnifico

Posted by MGK Published in Comics, The Adventures of El Tyrano Magnifico

14

Feb

11

Feb

Heroes:

A-List: A hero who is capable of sustaining their own series for an extended period of time (possibly more than one series, but at least one.) If they guest star, they are given major billing on the cover and their presence is usually intended to be a sales boost to the title. May be known to the general public, although this is not a requirement. They are almost immune to comic book death; if they do die, their books do not cease publication and the character returns from death in no more than five years. Examples: Superman, Green Lantern, Spider-Man, Captain America.

B-List: A frequent recurring hero in their fictional universe, someone who is usually a regular in an ensemble book. They may or may not have gotten their own series, but usually have not been able to sustain one for more than about five years. They are generally popular, to the point where a casual observer might think them to be more popular than an A-list hero simply because of the clamor for them to get their own book. They make guest appearances on a fairly regular basis in other books, but are not always billed as such on the cover. They are relatively safe from comic book death, but they can die in major crossovers; however, they usually return within five years as well. Examples: Martian Manhunter, the Thing, the Beast, Guy Gardner.

C-List: These heroes usually enjoyed a brief spate of popularity at the beginning of their existence, only to fall out of favor with the comic reading public. They rarely appear in their fictional universe, and when they do, as often as not it’s simply to provide a “shocking” death in a major crossover. (C-list characters’ deaths are almost always permanent; if they do return, it’s most often with a different character bearing the same name/costume.) They are highly unlikely to get their own book or even to make regular appearances in other books; while they have their fans, they’re generally considered “cult” characters at best. Examples: Speedball/Penance, War Machine, Vigilante, Judomaster.

Villains:

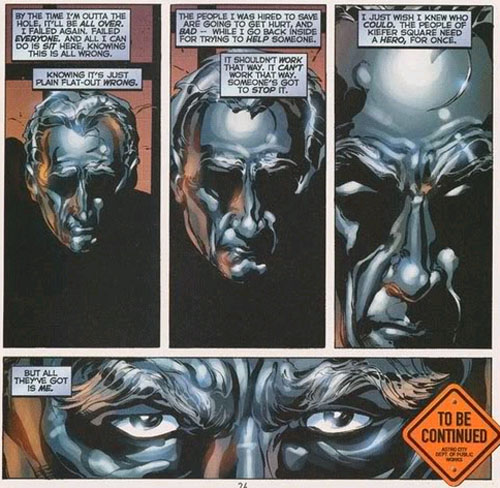

A-List: These villains have lofty goals (world domination, destruction of the universe, unmitigated chaos) and the ability to achieve them. Their appearance is considered a significant event every time they show up, usually an occasion for serious difficulties for the hero and a major extended plotline is needed to defeat them. Heroes sometimes need help against A-list villains, and they can be the headliners of crossovers (but not always.) Their defeats will be less ignominious than other villains, and they may even have a few victories notched up on their belt. (Sometimes they wind up having their defeats explained away as the work of imposters, clones, or similar.) If they do die, it’s almost guaranteed that they will return from that state. Examples: Doctor Doom, Darkseid, Thanos, Lex Luthor.

B-List: These villains tend to have less interesting, more self-motivated goals (personal wealth and power, revenge against the hero or society, et cetera) and are of a lower level of power. They are still significant threats to the hero (although they become less so over time–it’s more likely for a B-list villain to become C-list than A-list) and they generally remain thematically tied to a single hero. They put up a good fight most of the time, and are still exciting to read about, but generally more because of their particular quirks and personality than because they present a major obstacle to the hero’s life. They are not immune to comic book death, but it’s generally presented as a major event when they die. Examples: Kraven the Hunter, the Abomination, Metallo, the Parasite.

C-List: These villains are usually hired out or serve as lackeys to more powerful villains; regardless of who they originally battled against, they now make appearances in any book where a “disposable” villain is called for. They do not present a significant threat to whatever hero they face, and indeed they usually wind up defeated in comically ignominious fashion; their power levels may or may not be low, but if they are powerful, they are not skilled enough to use their powers in a threatening fashion. They are frequently the targets of “edgy” heroes or other villains, who kill them to show how tough/uncompromising they are. If they are killed, as with C-list heroes, someone else usually winds up taking on their mantle. Examples: Plantman, the Constrictor, Terra-Man, Weather Wizard.

10

Feb

Upcoming events in the previews for Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark

Posted by MGK Published in Bad Comedy, ComicsMarch 13, 2011. Julie Taymor tells critics that the show is “nearly there,” but following the tragic death of Reeve Carney in a “freakish falling eighty feet incident” that previews will continue for another six months. Newspapers react with additional derision. Glenn Beck informs his audience that Taymor “made the right call.”

May 3, 2011. New Spider-Man actor Steve Zablawsky breaks both arms in the “jumping handstand” sequence invented by Taymor, who felt the second act “was missing something.” Glenn Beck tells his audience to invest in Spider-Man tickets.

August 8, 2011. Rumors fly that the show will become Spider-Girl when Taymor lets a female actor, Tracy Maclough, audition for the part of Spider-Man. Taymor denies these rumours, insisting that she is merely interested in what a woman might bring to the role of Spider-Man, and “exploring all her options.” She also points out that women are more flexible than men, which, following the tragic death of Steve Zablawsky, could be an asset to the show.

December 9, 2011. When asked about the ongoing fiasco of the show’s pre-production, Bono says “Spider-Man? I’ve never heard of Spider-Man. What does he do, then?” Bono gets violently angry when people suggest he is in any way involved with the show, that he knows who Spider-Man is, or that he was having an affair with the late Tracy Maclough. Glenn Beck devotes a week’s worth of episodes of his show to Bono’s connection to ACORN.

February 7, 2012. Taymor fires the entire cast and replaces them with midgets after Marvel decides to end their involvement with the show. Spider-Man is replaced with the character of Tiny-Man. The Green Goblin is now called the Short Goblin. The goddess Arachne remains the same, but is shorter. “We can get a lot more height on the aerial stunts because they’re lighter,” explains Taymor.

March 22, 2012. Julie Taymor-Beck tells critics that Tiny-Man: Step Up The Ladder is “in no way exploitative. We respect these actors, and the characters they play, for who they are” after critics suggest that the Cannon-O-Midgets sequence, where Tiny-Man fights the Short Goblin fifty feet above the stage to save the lives of dozens of fellow midgets, is completely and utterly tasteless. Glenn Beck explains how the Cannon-O-Midgets represents the failure of collectivism.

July 4, 2012. After a tragic exploding fireball kills forty actors and four members of the audience during the Cannon-O-Midgets sequence, production is halted on Tiny-Man: Step Up The Ladder. Glenn Beck suggests that liberal elites killed the show out of jealousy.

October 7, 2012. DC Comics announces it is buying all rights to Tiny-Man: Step Up The Ladder and will hire Taymor to repurpose it as a Batman musical entitled Batman: Turn In The Dark. Taymor later explains her vision to reinvent Batman as a gargoyle who listens to punk rock and who is desperately in love with Gwen Stacy. Glenn Beck says “this will make Batman accessible to millions of people.”

7

Feb

2

Feb

Possibly Not Improved Archie

Posted by MGK Published in Archie (Improved Or Otherwise), Comics, Interactive Fun Time Party

(submitted by Ben Ferron)

1

Feb

Back when I did my post of the least essential Elseworlds, I had it in my head that I would eventually get around to doing the most essential Elseworlds. I tried a few stabs at the post, but kept running into the same problem, over and over again: even most of the best Elseworlds aren’t really essential.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t good Elseworlds. There are fun, pulpy adventures: JLA: Justice Riders, Superman: A Nation Divided, JLA: Age of Wonder, Batman/Houdini. There are thought experiments draped in superhero clothing, like Superman’s Metropolis or Red Son1 or Superman/Batman: Generations2 or World’s Funnest. There are Elseworlds which use alternate reality to tell stories almost entirely divorced from the meaning of the original characters, like Kal or JSA: The Liberty File. There are superhero epics that almost play more like a good issue of What If…? than as an Elseworld, like The Golden Age or JLA: The Nail.

All of these are good comics, and some of them are great ones (The Golden Age). But I hew to the idea that an alternate-reality story should, in some way, serve to illuminate the primary reality by shedding new light on the character. James Robinson’s revisions of the Golden Age characters in The Golden Age, while interesting, don’t really qualify. Superman: Speeding Bullets comes very close, by putting Superman in Batman’s shoes and using the familiar Batman story points to illustrate how Superman and Batman are totally different people and in fact could never be each other, but the third, redemptive act feels forced and unearned, in a “well it’s time for Superman to realize he’s still Superman” way. (It’s a story that needed to be longer, frankly.)

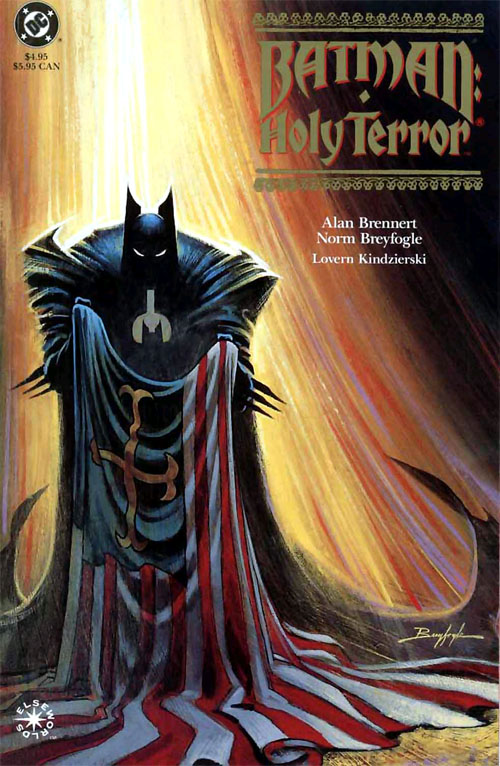

In the end, there’s really only one Elseworld that uses the alternate-reality trope to make a statement about the character it’s supposed to be about. Just one. But it’s one of the best Batman comics ever written, and of “the best Batman comics,” probably the least known.

Batman: Holy Terror isn’t just the best Elseworlds, it’s also really the first.3 I think its early nature is one of the reasons it’s so good; it avoids the formula later Elseworlds would eventually find themselves stuck within4 and just manages to be a compelling alternate-reality story because it dares to consider the fact that in an alternate reality, people make different choices.

In Holy Terror, the world is one where Oliver Cromwell survived the malaria that killed him in the “real” world and lived another decade, long enough to see the Protectorate he had established become firmly accepted. That’s a pretty bold premise, and Holy Terror doesn’t get caught up in explaining the 350 years of history in between then and now; it just sets out the current world, which is a theocratic American colonial portion of the Commonwealth.

In this world, Batman’s parents weren’t killed by a random criminal; they were killed by agents of the state for “seditious” medical behaviour (the comic never explicitly says that Thomas Wayne was, among other things, an abortionist, but it’s pretty clear that he was). Batman, instead of punishing crime, chooses to punish the unjust state. And that lets Alan Brennert make some pretty bold statements about superhero writing and Batman in a 64-page comic.

Firstly, Brennert asserts that superheroism as we know it is more or less explicitly tied to a free society. Costumed vigilantism doesn’t work in a security state. Of course, this is less revelatory a concept after Marvel’s entire output from Civil War through Siege more or less demonstrated, at length, why this was the case, but Holy Terror makes it far more explicit by asserting that superheroes are either troublemakers or assets to any dictatorial regime. Unpowered heroes5 are the former. Powered heroes are the latter, and they’re not simply assets for their abilities but for their very genetic stock, which is both horrific and rings a sinister-but-true note.

Secondly, Brennert explicitly makes Batman a terrorist in this. You can say that Batman is a heroic terrorist, certainly, but there’s simply no way that Batman, in this book, can be construed as anything but. (He even uses the word “jihad” to describe his struggle in his final speech.) That’s a very bold thing to say about Batman and one that, in later years, might not pass editorial muster.

Finally and most importantly, Brennert makes the case that Batman isn’t someone shaped by a traumatic incident, but someone reacting to the society which allowed that incident to happen. In this world, Bruce Wayne has all the resources that he does in the “real” world, but when his parents are killed, he doesn’t become Batman. He trains for it, but eventually abandons the calling to become a priest, and only resumes the idea of Batman when he learns that the state murdered his parents rather than a common criminal – and even then, he is plainly out for revenge rather than justice. Only when he finally realizes the full scope of what the theocratic state has become does he truly embrace the mantle.

This is a fascinating idea of what makes Batman be Batman, because it goes beyond the simple “parents shot -> fight crime forever” motif that most people start at. Most people, when they lose people in a traumatic criminal incident, do not decide to become a cape-wearing vigilante, even in the DC Universe, and Brennert suggests (and indeed explicitly says, in the final page of the comic) that Batman is really no different in this regard: what motivates Batman is not his loss, but the ongoing horror which causes that loss. In the “real” DCU, it’s crime and the continuing breakdown of society. In Holy Terror, it’s a tyrannical regime. This is a much more complex motivation for Batman than “parents dead,” and frankly it’s a superior one.

That’s why alternate reality stories can be truly great: they can take a different setting and use that setting to reveal more about the character’s inner self than might otherwise have previously been visible. Holy Terror is really the only Elseworld to do this so successfully; it’s why it’s the only one that is a must-read on that basis.

(And I just realized that I’ve managed to go through this entire post without mentioning Norm Breyfogle’s art once. Short short version: Breyfogle is, for me, the definitive Batman artist, and this comic is a superlative example of just why that’s the case.)

- Far more a victory of plotting than one of characterization. [↩]

- Which is just John Byrne playing around near-endlessly with the idea of continuity more than anything else. Byrne actually is one of the more adventurous users of the Elseworlds idea; his Elseworlds Annual with Superman in-never-revolutionary America is genuinely interesting stuff, even if it fails as a story in many ways. [↩]

- Gotham By Gaslight predates it, but Holy Terror was the first comic to ever have the Elseworlds stamp on it. [↩]

- “and here’s Alternate Reality Robin! And Alternate Reality Jim Gordon! And…” [↩]

- Like Oliver Queen, hung for treason on the first page of the comic. [↩]

Search

"[O]ne of the funniest bloggers on the planet... I only wish he updated more."

-- Popcrunch.com

"By MightyGodKing, we mean sexiest blog in western civilization."

-- Jenn

Contact

MGKontributors

The Big Board

MGKlassics

Blogroll

- ‘Aqoul

- 4th Letter

- Andrew Wheeler

- Balloon Juice

- Basic Instructions

- Blog@Newsarama

- Cat and Girl

- Chris Butcher

- Colby File

- Comics Should Be Good!

- Creekside

- Dave’s Long Box

- Dead Things On Sticks

- Digby

- Enjoy Every Sandwich

- Ezra Klein

- Fafblog

- Galloping Beaver

- Garth Turner

- House To Astonish

- Howling Curmudgeons

- James Berardinelli

- John Seavey

- Journalista

- Kash Mansori

- Ken Levine

- Kevin Church

- Kevin Drum

- Kung Fu Monkey

- Lawyers, Guns and Money

- Leonard Pierce

- Letterboxd – Christopher Bird - Letterboxd – Christopher Bird

- Little Dee

- Mark Kleiman

- Marmaduke Explained

- My Blahg

- Nobody Scores!

- Norman Wilner

- Nunc Scio

- Obsidian Wings

- Occasional Superheroine

- Pajiba!

- Paul Wells

- Penny Arcade

- Perry Bible Fellowship

- Plastikgyrl

- POGGE

- Progressive Ruin

- sayitwithpie

- scans_daily

- Scary-Go-Round

- Scott Tribe

- Tangible.ca

- The Big Picture

- The Bloggess

- The Comics Reporter

- The Cunning Realist

- The ISB

- The Non-Adventures of Wonderella

- The Savage Critics

- The Superest

- The X-Axis

- Torontoist.com

- Very Good Taste

- We The Robots

- XKCD

- Yirmumah!

Donate

Archives

- August 2023

- May 2022

- January 2022

- May 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- June 2020

- March 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- February 2007

Tweet Machine

- No Tweets Available

Recent Posts

- Server maintenance for https

- CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards

- CALL FOR NOMINATIONS: The 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards (the Theszies)

- The 2020 RSPW Awards – RESULTS

- CALL FOR VOTES: the 2020 Theszies (rec.sport.pro-wrestling Awards)

- CALL FOR NOMINATIONS: The 2020 Theszies (rec.sport.pro-wrestling awards)

- given today’s news

- If you can Schumacher it there you can Schumacher it anywhere

- The 2019 RSPW Awards – RESULTS

- CALL FOR VOTES – The 2019 RSPW Awards (The Theszies)

Recent Comments

- George Leonard in When Pogo Met Simple J. Malarkey

- Blob in How Jason Todd Went Wrong A Second Time

- Cindi Chesser in Thursday WHO'S WHO: The War Wheel

- Scott Hater in Bing, Bang, Bing, Fuck Off

- dan loz in Hey, remember how we talked a while a back about b…

- Sean in Server maintenance for https

- Ethan in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…

- wyrmsine in ALIGNMENT CHART! Search Engines

- Jeff in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…

- Greg in CALL FOR VOTES: the 2021 rec.sport.pro-wrestling A…