Twitter buddies were, last week, angsting a bit about how the cultural touchstones we had growing up are gradually disappearing and losing their relevance. Ghostbusters and Back To The Future lasted much, much longer in terms of cultural relevance than most movies do, partially because of the rise of cosplay and conventions, partially because each of the two franchises stayed fresh and new for longer than average (Ghostbusters from the first film’s debut 1984 to 1991 when The Real Ghostbusters ended its run, Back to the Future from 1985 to 1993 (again, from first film to end of animated spinoff series). And partially it’s because both of these movies were in the right place at the right time with respect to cable stations adopting the “let’s buy a given number of movies and air them endlessly” strategy that lasted for most of the Nineties and Aughts; you could catch Ghostbusters and Back to the Future and a select number of other films practically once a week on the likes of TBS or AMC or whatever other movie channels were available to you on basic cable, and even non-movie channels ended up having movie nights because it was and is a cheap way to fill up airtime.

But now with the rise of digital delivery, that era is basically coming to its end. People are losing the habit of watching movies on TV or indeed on any schedule other than their own. Which: this is great in many ways, of course, because you get freedom and a la carte selection and all that sort of thing, and you watch movies on your own time and etc etc etc. But the cost of that is that cultural touchstones have their power diminished and their period of relevance shortened. Which means that we are witnessing the rise of the first generation of people since Back to the Future‘s inception that don’t understand references made to it; it is passing out, finally, of the cultural jargon. As most things do, of course. Ghostbuster as well. Hell, Willow is practically an antique. The Princess Bride is the one that seems to be sticking and I think that’s largely to do with it having had wide distribution on kid-focused cable networks over the last decade, but who knows how long that lasts?

All of which is to say: those kids today, and in fact people in their twenties even, are much less connected to the movies I loved growing up when I was younger. On the one hand this is sad, because those movies are awesome. On the other hand, it means that this particular series of columns has way more breadth, because movies I have never considered to be particularly obscure are now, in fact, becoming obscure! Hooray! Or not.

The Freshman was never really a cultural touchstone in the first place, and as time goes on it becomes less and less well-known. This is not because it is a bad movie: it isn’t. It’s a very good one. But it is a movie that relies greatly on a previous cultural touchstone itself, namely The Godfather and Marlon Brando’s performance in it, and while some might argue that The Godfather is timeless – no, it isn’t, because nothing is timeless, and most people today are more familiar with second- and third-degree references to The Godfather than the film itself. So increasingly I see people even my own age are completely unfamiliar with The Freshman, and that is a shame.

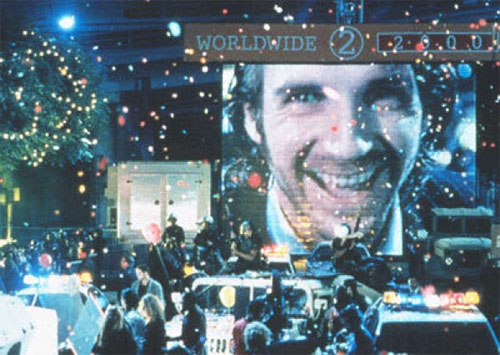

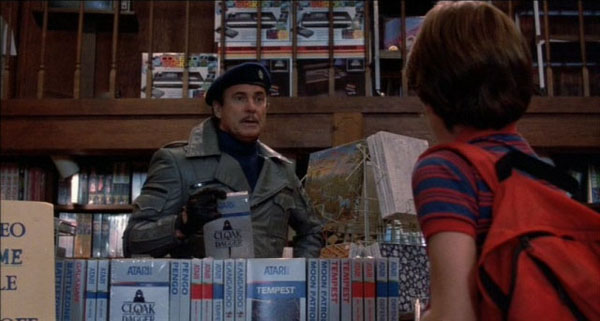

The basic plot is simple. Matthew Broderick is Clark, your titular freshman going to NYU, who arrives in New York and is immediately ripped off by Victor Ray (the late, great Bruno Kirby). Penniless and stuck, and with his horrible stepfather unwilling to help him out, Clark manages to track Victor down and Vic promises to make it up to him, despite having sold his stuff, by “getting him a job.” The job is working for Carmine Sabatini (AKA “Jimmy the Toucan”), who of course looks amazingly like Vito Corleone, although everyone explains to Clark not to mention this because Carmine is very sensitive about it. Carmine takes a liking to Clark, and offers to pay him to do some work for him…

…and then Clark has to pick up and deliver a Komodo dragon to an odd, out-of-the-way farm run by a crazed German (Maximillan Schnell).

…and then he’s introduced to Carmine’s beautiful daughter Tina (Penelope Ann Miller, having a ball with her character).

…and then he finds out Carmine has already told Tina that she and Clark are to be married, about which she is greatly enthusiastic.

…and then federal agents show up and tell Clark that the whole Komodo dragon delivery was the tip of a much larger thing.

…and this is about when he starts freaking out.

Those are your plot beats, but the sign that The Freshman is interested in being more than a simple caper comedy lies in the details. Indeed, many people upon hearing the plot are expecting a zany romp, but the movie isn’t really that interested in being zany the excellent bit with the Komodo dragon notwithstanding). It’s much more contemplative than that; still a comedy, to be certain, but a gentle one. Admittedly, it is gentle like the way Carmine is gently re-arranging Clark’s life without talking to him about it first. It doesn’t meander; everything is done with purpose and in its own time.

The Carmine/Clark relationship is the heart of this movie and what gives it dramatic heft. Carmine may be a mob boss or may not be (they hedge about this quite a bit), and he definitely has an iron will, but Carmine is clearly generous and loving as well. Late in the film, he goes to visit Clark and the two talk about children’s books, and Clark’s late father, and Carmine asks Clark to tell him one of his father’s poems, and it’s a wonderful, intimate little scene about a father with no son and a son who lost his father, both of whom clearly respect and like the other greatly, but who are also divided, at the moment, by little things like “being a mob boss” and “federal agents breathing down Clark’s neck” and even though these things are never mentioned they are addressed.

A lesser film would have simply indulged in Godfather references until the audience was mumbling “leave the guns take the cannoli” in their sleep, but this movie doesn’t go that route. Marlon Brando’s callback to Vito Corleone is only skin-deep; Carmine is a different character, a different person, and in this, Brando’s last great role, he manages to convey that difference while using all of Vito’s visual and audible tics. That Carmine looks like Vito is only the movie’s best running gag, and not its interior life. And this means you don’t have to see The Godfather first to appreciate The Freshman, because this movie isn’t about another movie. Honestly, so long as you know Vito Corleone exists, you will know enough to enjoy this flick.