Art of course by my partner in crime, the dynamite Davinder Brar.

12

Oct

9

Feb

So I started doing these things almost two years ago now, and I’ve gotten self-righteous emails about them at times. I’d figure I’ve gotten maybe two for every post (not sequentially, just overall). There’s the “who do you think you are” variety, of course, and the “why don’t you use all this talent to make something yourself” sort (because I talk so much about the writing I do that’s not for this or other sites, you see).

But one letter I got stuck with me, and that was a mail complaining that everything I was writing was setup. There wasn’t any payoff. Now, there are reasons for that, of course. These are essentially pitches to readers; a series of tests to see if what I like to write about is what people want to read. And, on the off chance I ever get to use them (writing Legion, or far more likely adapting what I’ve presented here for my own use in other formats and settings), I don’t want to give away the endings.

But let’s be realistic: the odds of me getting to write the book are dramatically low, even should I get the level of success necessary for DC to take a shot with me, because the Legion is a core property. (How many years did it take for DC to let Gail Simone write Wonder Woman?)

So I figured that for this – the last one of these, and this time I mean it – I’d change things up a little and give you more than just a teaser. Something fleshier. This was one of the first ideas I had when I started doing this thing two years ago – I referenced it in both reasons 6 and 29 of the original thirty – and it’s still, out of all of them, probably my favorite. So call this my 33rd birthday present from me to you. (I would’ve gotten you a card, but I’m cheap.)

I was not a big fan of the Mark Waid reboot of the Legion when it first hit stands four years ago, and even now – having developed a better appreciation for the ideas and capabilities behind the reboot – I think he botched some things. I’ve discussed these elements before and don’t feel the need to drag Waid through the shit all over again.

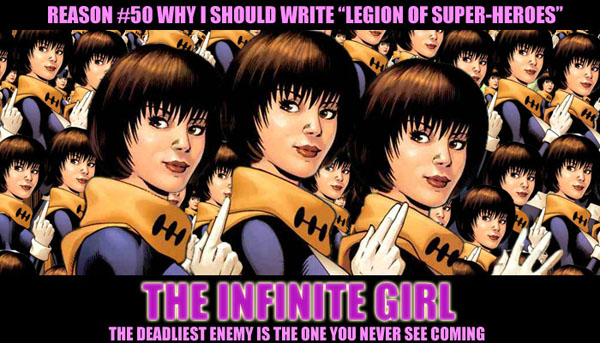

One thing I particularly disliked at first was his reimagining of Triplicate Girl. Removing the “triplicate culture” that previous versions of the Legion had had and replacing it with a hive mind sort of gestalt being? It was weird, and at the time I felt it was pointlessly showy. I missed the idea of “tri-jitsu.” Worst, it was kind of creepy.

But then I started thinking about it some more, and I realized – it was kind of creepy! And this wasn’t bad – it was great! Because in issue #3, Triplicate Girl’s origin story? Is told entirely by Triplicate Girl herself. This immediately offers the possibility of an unreliable narrator. Unreliable narrators are one of my favorite storytelling devices because they really let you fuck with a reader’s head in a way that the reader will not only not get irritated by, but will instead thank for you doing so (when it’s done properly).

In issue #3, Triplicate Girl explains that she has no memory of what happened before the great disaster on Carggg that left only her; that she has no memory of how she came to be or how she got her power to self-replicate or how it works; that when she split her three-selves off to join the Legion from the rest of herself, that those three grew isolated from the rest of her self-society.

Bullshit.

All of it.

This is what really happened:

The entity now calling itself “Luornu Durgo” was created in a laboratory on Carggg, a small self-reliant, self-sustaining planet outside of the usual galactic traffic, one of the long-lost remnants of the colonization protocols initiated by President Thomas Lorenzo in the late 21st century when Earth’s ecosystem was on the brink of total failure. They were looking to create a next-generation antibiotic – a living compound, something that would kill virii by absorbing their genetic material. A “virus-eater.” But what they got instead was something that reflexively absorbed genetic material.

The real Luornu Durgo was a lab technician who wasn’t careful putting the failed experiment into the matter disposal unit. The compund killed her quickly, in a matter of seconds. When it did so, however, it imprinted upon her genetic template, merging itself with her, gaining sentience at the same time, marrying intelligence to a natural drive to consume. The new entity quickly realized that if anybody realized what it – she? – had done it would be destroyed, and pretended to be Luornu for a period of weeks.

During that period it started absorbing other citizens of Carggg, always careful to do so in a manner that would not raise suspicion. Each time, it gained the ability to generate a new body – and more interestingly, every time it did so it created more personality within itself, gradually becoming the hive mind it would later in fact claim to be. It/she felt guilty about killing people, but the urge to absorb was of it/herself; there was nothing to be done.

Of course, eventually the Cargggites realized what was happening, almost too late to even do anything. By that point Luornu (for so they now thought of herselves) was almost a fifth of Carggg’s population and growing rapidly. What happened next was a short and brutal war, which ended when the last bastion of Cargggites launched bradyonic bombs in a last-ditch, suicidal effort to destroy her before she captured the planet’s only remaining spaceport. The bombs wiped out all life on Carggg…

…except for Luornu. A few of her bodies were in an underground bunker at the time, and that was how she learned that the bradyonic energy – also used in teleporter technology – had not destroyed her bodies but instead, in a sense, hyperlinked them. She could now transfer her accumulated bodymass between bodies at any range, any distance. But she couldn’t teleport off the planet or anywhere else she wasn’t already, so she was trapped – and always feeling the hunger. She rebuilt the planet more out of boredom than anything else, taught herself whatever books could teach her. She continued to feel conflicted and guilty for obeying her natural urges, and tried to use the isolation to teach herself restraint.

When the United Planets exploration crew finally arrived planetside, it took all her control to keep from immediately consuming them. She spun her story of destruction and mystery, and then separated three bodies from her packself to go with them.

The restraint didn’t last, of course. She spun more bodies off herself the moment she landed on Earth and went hunting, never letting her primary three consume anyone even as they joined the Legion. This time she had the benefit of experience; she consumed the valueless, the ones nobody would miss, the underclass and criminals which avoided the Public Service. There were hundreds of millions on them in every system in the UP, plus the entire population of Rimbor and countless fringeworlds. When the Public Service was destroyed in the wake of the Dominator War, it got even easier.

All the time she kept rationalizing. Nobody would miss these people. They were leeches, parasites, better off gone. If the Legion knew, they’d destroy her, so she couldn’t tell anybody. Saturn Girl’s telepathy didn’t pick up any of this – for much the same reason that somebody drinking water from a lake doesn’t taste the whole lake.

Nobody should have noticed; nobody should have cared. But even criminals sometimes have an influential friend, and two of them were old gang buddies of Jo Nah. When one of them disappeared and the other called for help before disappearing herself, Ultra Boy took an interest, and started investigating. Not well, because he wasn’t a natural detective by any means – but he didn’t give up. It took him a long time to piece together the chain of disappearances, longer still to see the spikes wherever the Legion had had a mission.

By that point, she was one billion strong and counting. And hating herself, none moreso than her selves in the Legion – one of whom was now in a serious relationship with Element Lad. (It helped that, even though she believed she would never consume a Legionnaire, that the auras generated by the flight rings prevented her from doing so.) That self, more than any of the others, was purely restrained, never absorbing anyone. Even the other two-thirds of Triplicate Girl did so occasionally. But that one, the one dating Jan – no. Could never do it.

And that’s where the story really starts – when Ultra Boy confronts her before the Legion, demanding an explanation he doesn’t entirely want. That’s when it’s revealed that Triplicate Girl is really the Infinite Girl, as she sprouts bodies into the room faster than anybody can imagine, flooding the Legion with duplicates of herself. They may not be superpowered, but what does that matter? They can carry weapons, and they can kill any organic lifeform not wearing a flight ring – and increase their numbers at the same time. And the Legion doesn’t want to kill them – not even those with more violent tendencies (like Timber Wolf or Shadow Lass) want to carve up someone they thought of as a friend.

The Legion is swiftly divided between those taken prisoner and those managing to escape, to help in the frontlines of an instantaneous war as Luornu attacks the United Planets on a dozen different worlds simultaneously, her fight-or-flight instinct kicking in on a genocidal level. The prisoners have to escape so Brainy can come up with a plan. Element Lad has to convince the sole remaining Luornu to help, and she has to find it within herself to do it.

And in the end, they find a way to beat her – and, yes, destroy her – within a matter of hours. But it costs them one of their own; there’s no way around it. Who do you think goes? The last sane Luornu-self, desperate for redemption? Element Lad, determined not to let his lady die entirely? Ultra Boy, convinced he has to finish what he started? Maybe it’s someone else. But not everybody gets out of this one alive.

—

And that’s that. Thanks for reading it, but now I’m done.

4

Feb

“War. War never changes.” Which is why in order to beat it, you have to change instead.

Terraforming? Doesn’t work.

Well, it does. It just doesn’t work at any speed that’s meaningful to any civilization. Even the quickest terraforming techniques take centuries to transform dead worlds into only moderately livable ones. (There was this one set of experiments with the Speed Force in the mid-2600s – but that’s a whole other story…)

Think about that for a second. Hundreds of years. Most humanoid civilizations don’t have the lifespan necessary to consider terraforming on any serious emotional or mental level. Think about how hard it is to get global warming policies enacted right now, when we pretty much know that we’re fucked as a species if we don’t get on the horn immediately. Now let’s extend the scope of action even further. That’s terraforming. It’s hard for a government to initiate a series of actions that have the potential to outlast the lifespan of the government itself.

So terraforming barely ever happens. Alien civilizations guard their lush systems with near-paranoia because the perception is that that’s all there is – and as perceptions go, it’s mostly not wrong. Dead worlds serve as mining camps and little else, because everybody learns soon enough that there’s no point in stripping your own world’s metals when there are perfectly good asteroids nearby.

But of course there are outliers. Fringers ekeing out an existence on rimworlds barely capable of sustaining life. The United Planets, the Khund, what used to be the Dominion, and every other small stellar empire occasionally send out a tax collector, but really, who cares? They show up every so often, sell some raw minerals, buy some food – it’s money into the economy and who cares about them otherwise, right?

But there’s one system, smack dab between the Khund and the United Planets – the two giant gorillas of interstellar politics. Four planets, all barely inhabitable, all desert worlds with fringertowns and rimvilles. They’re called the Sandworlds, when anybody bothers to wonder what their name is. Nobody lays claim to it; the locals trade with both the Khund and the UP. And that’s pretty much it.

Until a routine UP surveyor ship, using the system as a stop point to recharge jump engines, notices that one of the worlds is suddenly a lush jungle paradise. And Khund intelligence finds out soon after. And then suddenly the issue of claim is very important indeed.

Nobody quite knows how that desert world became a rich life-bearing planet. (Even if the world was transformed into fertile soil, where did all the plants come from?) But it doesn’t matter, because this is the Holy Grail of interstellar colonization. (How much energy does it take to do this thing, anyway? Where do you even begin to get it?) And the fleets mobilize, and move into the Sandworlds system, because you can’t let anybody else have this technology if they won’t share it.

And that’s why Timber Wolf in particular is positive that somebody’s running a giant scam. Somebody wants the Khund to go to war with the United Planets. He doesn’t know why – but he knows this stinks. And what’s more, the United Planets government won’t let the Legion investigate, because they want that technology for the UP so badly they can taste it and no way some bunch of punk kids are going to ruin this – so the Legion gets drafted into the UP military.

This isn’t a story about battles and war – like we said, war never changes, and it’s always the same story with different trappings. This is a story about spying. Because, more than most superhero teams, the Legion has a proud tradition of being willing to out-sneak the bad guys just as often as they out-fight them. This is a story where Mon-El and Ultra Boy are the distraction to let Invisible Kid and Chameleon do the real work.

In short – this is a story about the Legion Espionage Squad.

10

Dec

The idea of “hero created in response to other heroes emerging, by people feeling threatened by said heroes” is again nothing new. However, the reason it isn’t new is because it’s timeless; it’s the classic human arms struggle (as power struggle) transposed to superheroics, which lends it a sense of immediacy, and it doesn’t have a predetermined ending. Sometimes it ends well, sometimes it ends in tragedy. That’s why it’s a deep well.

When the Legion emerged as a true force in intergalactic politics, there were of course those who felt threatened. Metahuman-level power had always been isolated, and usually culturally specific: Titanian telepathy, Braalian magnetism, Coluan intelligence, and so on. The conflux of the best and brightest from all corners of the galaxy was intimidating; many a military strategist had often wondered how a super-unit of the greatest combatants would serve the United Planets, and now that super-unit existed and was almost totally unaccountable to anybody. Every planet instantly began a new super-agent program, every last one of them in secret.

One planet had a particularly gifted biophysics researcher who thought he had cracked the secret of personal teleportation as a genetically derived superpower. They found a volunteer – an idealistic young captain, honest and compassionate and brave and extraordinarily grounded. They began preparing immediately, and readied the experimentation chamber. When the chamber blew up with the young captain inside, the government killed the program in a flash. It never happened. No evidence remained.

But soon enough, people started turning up dead. Unrelated to the experiment, understand – these were largely murderers, rapists, and the like. All of them stopped in the act. The religious spoke of an avenging angel; the secular muttered of government conspiracies. They were both, in a sense, correct.

The young captain was of course not dead. The experiment had worked perfectly;he could teleport anywhere he wanted, anytime. It was easy. He could even “look” in advance, sense where was safe to land, where he wanted to go (the scientist knew that such an ability would be necessary, lest teleportation be useless without a map of where you wanted to go, preferably with mathematical coordinates). It was flawless in every respect but one.

He couldn’t stop “looking.”

Every second of every moment of his life now, he sees people hurting, assaulting, enslaving, raping, killing other people. And he sees all of it, everywhere. For a given value of “everywhere” that’s rapidly expanding as his ability to “see” grows. Almost anybody would be driven insane by the sheer sensory overload, but the young captain was a man (or woman, actually – gender isn’t important to the character) of exceptional mental fortitude, and discovered that it was possible to retain some slight degree of sanity through action. (If the only way you could keep from going insane was by killing total bastards, what would you do?)

There isn’t an armory in the universe he can’t get into, not a criminal in the universe that’s completely safe (that’s the advantage of total surprise). He stays awake for weeks thanks to pharmacology and willpower because he can’t sleep unless he’s so exhausted that he passes out, not without seeing people violently dying right in front of him, tens of thousands at a time. (If you could stop someone you’ve never even met from being murderered, wouldn’t you feel the need to do it?) He flits across the United Planets faster and faster, never anywhere longer than twenty seconds, usually less than five.

He’s been lucky so far; hasn’t killed anybody who only appeared to be killing someone or doing something as bad. How long before his sanity gives out entirely? (What he’s going through is literally inhuman.) How long before people start blaming the wrong people for his kills? How long before he kills someone important and that fucks up interstellar politics for way more people than he can ever save? How long before some innocent guy just playing “Slaver and Property” with his girlfriend gets two in the head because the Everywhere Man didn’t have enough time to properly assess the situation before heading off to the next galaxy to kill somebody else? Can he really keep his perfect record forever?

Can they stop him?

Should they?

3

Dec

Personally, I think the moment everybody realized this particular post would be about dinosaurs in space with lasers, that I really could have just written “Dinosaurs, in space, with lasers” once, copied it, and pasted it two hundred times and everybody would still be happy. However, I like details, so…

The idea that the dinosaurs had mastery of high technology and just left Earth, rather than going extinct because of a meteor strike or geological shift or disease or anything, is not one that is particularly revelatory in science fiction. I mean, once an idea makes it into an episode of Star Trek: Voyager, you know it’s not going to be particularly original. Heck, one of my favorite sci-fi trilogies, Robert Silverberg J. Sawyer’s Quintaglio series, is all about dinosaurs in space. (In fairness, Sawyer’s books were about genetically modified dinosaurs transplanted through space from Earth to a different planet by super-advanced intelligence assisted by something not unlike God, and who had to undergo their own accelerated Renaissance in order to leave their planet. But, still – dinosaurs in space.)

That having been said, while the idea isn’t new, it is indescribably awesome, as it combines dinosaurs with space (and lasers, of course). The trick is to integrate it into the DC Universe proper.

The First Ones left Earth a hundred and twenty million years ago, when just about every civilization worth mentioning that still exists was in its cradle or not even alive yet. (The Oans were only starting to consider building the Manhunters at this point – that’s how old we’re talking.) They were already brilliant, their natural intelligence enhanced by a primordial telepathic hive-mind, the Oneness, as they first began psychic study before even bothering to consider engineering or technology – and when they did consider those things, they advanced millennia in heartbeats as the wisdom of one hundred thousand First Ones (who, for the record, were much like Tyrannosaurus Rexes, but herbivores and with larger arms – but the same enormous size, because if you’re going to have dinosaurs, I say you don’t puss out and make them human-sized dinosaurs) was brought to bear upon arithmetic, algebra, calculus, physics, quantum calculation, and anything else you would care to name. Sciences fell like dominoes.

Realizing that their species would dominate the planet so greatly that they would endanger all other life upon it, the First Ones chose to segregate themselves – at first only from their home planet, but eventually deciding that the potential for interfering with other species was too great, and deciding to pursue the path of study and solitude. They built ships and went out into the stellar void – far, far outside any habitable galaxy. They collected stellar matter from white dwarves and black holes, re-engineering it into a working, everlasting ultrasun, then created a massive world to orbit it (and a moon, mostly because they wanted tidal patterns so the beaches would have waves so they wouldn’t grow homesick). They cloaked their new system in a cloud of gigatonnes of dark particulate matter, and seeded it with life, and settled down, and studied.

Their science grew profound and inexplicable. If they had wanted to conquer, it would have been a simple matter, but their passions lay in simple learning (and banana leaves). They conquered aging, and took pleasure in ideas – and they never lacked for new ideas. They created observascopes to study the universe ongoing, and watched millions and millions of years of stellar history unfold.

And then, one day, about a hundred thousand years ago, one of them died. This was a tremendous surprise, for he had not died in simple accident, nor had there been any warning. He simply lay down and stopped, his bodily functions ceasing in an instant. The mental conversation within the race – now twenty-two billion strong, as they had been for fifty million years – spoke of nothing else. Truthfully, the species was energized by the sudden existence of a problem they needed to solve.

They never solved it. A species that conquered all disease could not defeat this foe. Some theorized that it was the natural reaction of a species to a lack of mortality – bodily functions filling the void created by genius. They tried to recommence breeding, but discovered – much to their surprise – that the species had become sterile, it having been eons since any of them felt the need to reproduce. Vigorous debate ensued as to the next course of action to be tried, as the deaths accelerated, but the First Ones had a new problem: although they were naturally intelligent, their survival demanded that their thought be advanced by their primordial Oneness so they could operate the insanely complex devices that kept them healthy, operated their crops, kept their very world stable.

Every time a First One died, the Oneness was weakened. Every time a First One died, every other one became just a little bit dumber.

They continued to debate and plan even as their intellects steadily shrank. By the time they were no smarter than the average Coluan, about a thousand years ago, a final plan was determined. They invented one last great work: a ship so vast it was larger than most moons. The remaining survivors – about one hundred thousand strong – got aboard it and left their world, already slowly beginning to disintegrate.

All they wanted was to see their home one last time, and to die where they were born.

Unfortunately, it was now occupied. And although the First Ones were a peaceful race, by instinct and creed… they nonetheless knew how to construct and design great weapons. They did not want to use them, you can be sure of that… but they would use them, if they felt it necessary. Because when you only have one thing left to you to do and to want, you want to do it very, very much indeed.

The Legion has to stop them. Or save them. Or both. Or save the United Planets. Or stop the United Planets from destroying them. Or both. They have to find the lost world of the First Ones. They have to make sure that the First Ones destroyed it. Or both. And Brainiac Five has to deal with the existence of an entire race who outclasses his brilliance on a bad day, which might be harder than all of the other things put together…

11

Nov

The Legion has a time machine.

So why is it that the only place they ever go, ever, is the present day DC Universe? Surely there are all sorts of other places they can go?

It doesn’t have to be Shadow Lass, of course. “Talokian” just sounds kind of like “Connecticut,” and I like bad wordplay sometimes. And it doesn’t have to be Camelot, either. (Although more opportunities for the Legion to meet up with Etrigan are, in my book, always to be wanted. Mostly because Etrigan is bad-ass, and rest assured I am fully on board with Etrigan being an evil bastard rather than a heroic demon, because the former is awesome and the latter is kind of dorky.)

But there are options aplenty. Anybody who has ever watched an episode of Doctor Who knows this to be true. Pick an interesting historical setting. For style points, make it one with some strange thing that has never been explained, and explain that strange thing (preferably in a convoluted manner involving Brainiac Five blowing something up in the name of Science). The Tunguska Event, for example, is suitably mysterious (we think it was a meteorite, but we can’t be sure), and involves a large explosion, so there’s one right there that comes pre-suitable.

But wait! How about “how did the Aborigines get to Australia?” (Nobody knows.) Or “where’s the Ark of the Covenant?” (Nobody knows that either, except possibly for a few people and they aren’t telling if they do.) Did the Legion get involved in the quiet, subtle feud between Belisarius and Justinian? Did they at some point run into the Comte de St. Germain? (Actually, he probably made it to the 31st century. Seeing as how he is the Comte de St. Germain and all. Hey, maybe he’s R.J. Brande!) Do they know what happened to Judge Crater? Maybe he was a monster of some sort. Maybe they were responsible.

All of this should not be taken to transplant the Doctor’s storytelling model onto the Legion – nor, for that matter, Booster Gold’s, considering that Booster has the “hero who travels through time and fixes things” niche and I don’t think anybody should mess with it or make it redundant. No, the Legion doesn’t travel through time and do heroic things proactively. For them, it is entirely reactive – the Legion just has a knack for getting shoved to the ass end of time by some horrendous cosmic force and having to deal with that. (I mean, come on, their greatest foe is called the “Time Trapper.” That is kind of a hint.)

And of course, time travel doesn’t have to be limited just to Earth, and the Legion knows about the dangers of time travel and not altering the flow of history and blah blah blah responsibility-cakes. Imagine shoving them back to the Dominion homeworld just before the invasion of Earth (the one with the Khund and the Thanagarians and the Gil’Dishpan, not the one just recently in the 31st century with the robo-virus). They’ve got a front row seat at a decimating event in Earth’s history, but a necessary one. Think there might be conflict?

15

Sep

One of the reasons I think the Waid/Kitson threeboot version of the Legion was fatally flawed from the outset is that its concept of making the Legion an oppositional force was wholly at odds with the core Legion concept, which tends to be utopian and status-quo defending rather than revolutionary and game-changing. Sure, you could argue that the revolutionary nature of the Legion was heroic in and of itself since they were rebelling against a stagnant society which needed them, but Waid started sabotaging this practically from the first issue by writing numerous Legionnaires’ characters as dilettantes, thugs or cynics. More realistic, maybe, but it’s the type of realism I think is somewhat misplaced in my comic book about teenaged superheroes in the far future.

Worse is that in practice, the revolutionary concept only really has one story hook to go with it, which is “Legion versus entrenched authority.” Comic creators of all stripes have come back to this trope again and again and largely without exception the stories are subpar. (Example of an exception which proves the rule: the v4 Earthwar saga, wherein the Legion fought entrenched authority that was corrupt and evil, namely the Dominion which had quietly taken over the Earth. That is fine. Of course then about twenty issues later we had the “outlaw Legion” arc, which sucked so hard it created its own portable vacuum.) The Legion, from my perspective, is interesting when they fight supervillains – the concept is primarily one with its roots in space opera and traditional superheroics, and I don’t think it lends itself well to stories attempting to deconstruct social politics in this regard. (In others, it can excel.)

Truthfully, I think a large part of the fondness for Geoff Johns’ “I Can’t Believe It’s Not The Paul Levitz Legion” exists because the current Legion seems so fundamentally detached from the traditional superheroics typically associated with the team. Jim Shooter’s run has largely been marked by a vivid feeling of jumping through hoops to give the new conceptualization of the team lip service, resulting in the joyless vaguely-superheroic process stories that I loathe combined with soap-opera plotting.

But the answer to all of this is simple. It is painfully simple.

Shove the series forward a year.

After all, back during the “One Year Later” event post-Infinite Crisis (which almost entirely backfired, but that’s not really relevant here), the Legion was unique in that it didn’t advance a year, presumably because Waid didn’t want to bother and because in a series a thousand years apart from the rest of DC continuity there wasn’t any need. But a one-year gap gives a writer carte blanche to change the social status of the Legion as he sees fit, because in a superheroic universe a hell of a lot can happen in a year’s time.

What’s more, the one year leap creates a jump-on point for new readers, if handled correctly, and stimulates excitement among older readers. Legion fans may now debate the merits of the Keith Giffen v4 “five year gap” Legion, where Giffen (and Tom and Mary Bierbaum) shoved the series forward five years, but when they debate it they’re arguing about the execution of the story and whether the plotting and characterization were good or bad. I’ve never seen anybody suggest that the five year gap wasn’t a good idea in and of itself. Creating an instant in media res situation for all readers is exciting, and with proper followup can become epic.

Imagine, the first page of a new issue. A starfield on inky black, with thick white text covering the page, not unlike a still version of the scrolling text in Star Wars movies.

It is one year since [insert events of previous storyline here.]

The Legion of Super-Heroes is stretched to its breaking point. The Controller Virus decimated the Science Police in every major star system, and now the newly-named Science Pirates attack interstellar shipping routes with every passing cycle. Sensing weakness, criminals and outlaws now attack throughout the United Planets constantly. Only the Legion stands between them and the starvation of every outlying frontier colony on the Rimward Fringe, thanks to a desperate United Planets giving them full enforcement authority.

Other problems abound. The Khund, silent for centuries, renew the operation of their warfactories. Scientists report an increase in inexplicable gravitic anomolies. The genius race of Coluans faces near-extinction in the face of the Lemnos Plague, even with Titanian medipaths working around the clock for a cure. Orandian refugees cluster on Earth, demanding recognition and planetary allotment as the independent nation of New Orando. Rumours swirl that the Robotican Front has finally built the M.E.S.S.I.A.H. which will free them from organic bondage.

And Brainiac Five has been missing for seven months.

19

Aug

Honestly, I had been planning to stop doing these at #50, because there’s a limit, even for me, but although the whole exercise is just a fun one, the depressing possibility that Geoff Johns’ “I Can’t Believe It’s Not The Paul Levitz LSH” will become the de facto Legion kills a lot of that fun, much in the way that watching people squander vast storytelling potential in order to appeal to a cadre of steadily shrinking, impossible to satisfy, aging bitter fans can… hey, wait, that’s exactly what would happen if they went with the Johns Legion as the “primary” Legion!

Anyway. Soapbox mode: off. Hope that they stop constantly rebooting the Legion to save it: on.

I’ve said before that you can’t have the Legion without Cosmic Boy. He’s their Captain America. He’s always The Leader, regardless of whether he’s actually leading or not. And this is fine and good.

However, currently in the Legion, there is no Cosmic Boy. He went to the future with the “Knights of the Galaxy” in a thinly veiled homage to the original Superboy-meets-the-Legion story, which depending on your point of view was either brilliant or hokey. (There hasn’t been a lot of middle ground there.) So let’s bring him back! But I don’t want him to be the leader. Surely there’s more interesting things to do with Cosmic Boy than just have him be inspirational and leader-ish all the time, right?

So here’s what happens: he comes back from the future, and he doesn’t remember a-ny-thing. Nada. Zip. Zilch. The big donut. He knows he went, but everything after he stepped through that time portal? Blank. He has no idea what happened, and really, when you think about it, doesn’t that make sense? To protect the timestream and all.

…except sometimes he has flashbacks. Sometimes they’re weird. Usually they’re scary. Often they’re violent. Sometimes they’re painful. And he hasn’t got any idea why he’s having them.

Maybe a 41st-century Saturn Girl equivalent stored memories he would need in his head, allowing him access only when she felt he needed to have them. (41st-century telepathic techniques are, unsurprisingly, vastly more advanced than 31st-century telepathic techniques, so the actual Saturn Girl can’t get to the memories in question. “It’s like trying to derez a forcefield with a squirt gun.”) Maybe those memories are a guidebook for him, meant to unlock only when the time is right and the knowledge stored within can help the Legion.

Or maybe, nobody’s fault, he saw things in the 41st century he Wasn’t Supposed To Know. (Time travel. It’s a bitch like that.) And for the good of everybody, he agreed to have parts of his memories locked off so he couldn’t endanger anybody. Except memory locks aren’t perfect; they need regular maintenance, especially for an intelligent and strongwilled person like Cos. Maybe that stuff He Wasn’t Supposed To Know is bleeding through, infecting his real memories, combining and swirling…

Or maybe it is somebody’s fault. Maybe the flashbacks aren’t bleeding through by accident. Maybe a nefarious being (take your pick) is mining his head for tactical advantage, and the flashbacks are spillage as the nefarious memory thief digs deeper and deeper.

Or maybe the stuff he saw wasn’t stuff He Wasn’t Supposed To Know in the affecting-the-modern-day sense. Maybe the Knights of the Galaxy weren’t a 41st-century equivalent of the Legion, but instead a psychotic fascist government which pulled him to the future seeking ancient knowledge, except they screwed up and got him too early. But they tortured him anyway, because heck, maybe he’d know something helpful. He barely escaped, but now he’s suppressed everything he saw and experienced – because that’s how bad the future is. (Maybe the 41st century version of the Legion, a desperate but heroic band of rebels, were the ones who set his escape in motion.)

Or maybe it’s a combination of all of the above, sorta, with the Knights of the Galaxy still evil, but instead of tricking Cosmic Boy for the purposes of mining his brain, they snagged him to turn him into a living weapon against the past itself. The flashbacks are a combination of instructions and post-traumatic stress disorder, with the former hidden deep within the latter.

Whatever happened, the one thing that doesn’t change is that Cosmic Boy can’t trust himself to lead the Legion, can’t allow himself to put lives on the line when he’s in such a state. So he sits back in the membership, acting as a role player rather than a commander. Practically the whole team defers to him naturally (because he’s Cosmic Boy), but he doesn’t allow them to do it if he can help it (again, because he’s Cosmic Boy). He needs to figure out what happened to him before he can assume his proper place.

Oh, and here’s one more possibility for you:

Maybe he never went to the future at all.

22

Jul

(Seriously, I have like the worst cold ever, I’ve been all ugh for like two days now and the only thing I have in the hopper is this. I usually wait three or four weeks to post a new one of these because I like to space them out but I want to get some content up before I keel over and die of the coughing, so here we go.)

One of the things I’ve said before that I love about the Legion is the variety of setting, all these weird planets (and, to be fair, normal planets) that can have drastically different ways about How Things Work. Coluans literally worship the concept of scientific research, Titanians don’t have a justice system like anybody else because they don’t need one because they already know if you’re innocent or not, Naltorians invented the concept of “pre-crime” ages ago, Tromians aren’t afraid of death because they believe in change as a spiritual systemic concept, the Khund have a belief system somewhere in between modern-day anarchic Satanism and Klingon warrior ritualism, et cetera. All of these societies recognizable to a standard (IE, “our”) perspective, but nonetheless different and with ramifications upon the non-cognizant intruder. (Or, as I once called it, the “Wesley Crusher Gets In Trouble On The Eden Planet” syndrome.)

Well, what about Rimbor? For years it’s been more or less a generic “bad seed” planet. It has gangs! And crime! And… well, that’s mostly it. Ultra Boy is known to have a rough background because he’s from Rimbor, but what does that mean in larger context?

The thing that interests me is that Rimbor, even in Mark Waid’s reboot where the United Planets was essentially a going-stale utopia, was a crime-ridden scum planet. That has potential, because the fact that Rimbor was gangland central even in a utopically-designed collective implies to me that the United Planets knew exactly what Rimbor was and purposefully tolerated it.

Consider, firstly, the concept of Rimbor as galactic equivalent of Australia. In the early days of quantum warp travel, humanity stupidly decided – not for the first time – that the solution to all societal woes was to get rid of “the bad elements,” and that the humane way to do this was to exile them to a nice lush planet somewhere out of the way. Unlike Australia, they actually got the “lush” part right this time: Rimbor was a resource-rich world, teeming with life, almost an Earth 2.0. And thus they dumped all the criminals they could manage and all those people who weren’t actually bad or anything but made the mistake of being the wrong person and the wrong time on Rimbor, and considered the matter done.

Unfortunately, the most powerful gangs had scientists in them, and the gangleaders quickly realized that they had all the means to get off Rimbor if they could manage it. Major gangleaders coalesced power around themselves, all attracting followers with the intent of getting the hell off Rimbor. Generations passed, and what happened on Rimbor became fairly unique; political power became neither hereditary nor democratic, but remained strictly a matter of personal charisma. Mistabigs and jonniroyales arose as the new leadership, each attempting to make his leadership permanent beyond their own lifespan, each failing. In an era where personal communication was instantaneous and widespread, and on a planet where destructive power was essentially impossible to coalesce on a permanent basis, progress only happened in incremental spurts.

But it happened, and four hundred years after Rimbor was colonized, they recontacted the United Planets (now utopic as planned, albeit with several false starts). The UP was somewhat horrified at the chaotic morass that was Rimbor (“one large jumpergang of a planet,” said one councillor), but wiser minds realized that, even in a utopia, there would be malcontents and rebels. So the Rimborian Compromise was introduced into UP law; a lengthy document that can be summed up in one sentence.

“On Rimbor, laws are technically optional.”

On Rimbor, enlistment in the Public Service was entirely a matter of choice (and one not often made); it bred hordes of free thinkers, philosophers, and artists alongside the criminal class which dictated day-to-day affairs planetside. (Most times the free thinkers and artists were criminals themselves. Way of the world, don’t you know.) Corporations flocked to Rimbor to maximize their profit potential by having a corporate base where law could be reformed at will, working in cooperation with the mistabigs; Silverale, 3B, S.O.D.E.R. and OmniNewsTimeNet all call Rimbor their home now. The UP’s best soldiers come from Rimbor, because having to know how to win a knife-fight from the age of six tends to make you tougher than average.

Rimbor is large and chaotic and dirty, but it’s also the third richest planet in the United Planets (after Lexor and Earth). Teachers throughout the UP tell their pupils about the dangers of “lawless Rimbor,” which has a dual purpose – both to revile the greater portion of their classes and to keep an eye on those attracted to the idea of it. The Crime Planet is the back alley of the United Planets, but not by accident; when you need to find something in a hurry and you don’t care how you get it, Rimbor is always there, and someone can probably help you for the right price. But be sure to watch your back: the only lasting rules on Rimbor are the rules of the street. Don’t trust anybody; keep your secrets close; don’t trust anybody; fight on your own terms; and don’t trust anybody.

I’m sure all of this tells you a little bit about the character of Ultra Boy, of course. But that was kind of the point.

NEXT TIME: A Legion member with Issues ™.

15

Jul

From the email inbox:

Hey – I love reading your I Should Write The Legion things, but writing is only half of a comic. So my question is – who would be your ideal artist(s) for the Legion when you get to write them?

Firstly, I feel it’s important to emphasize that, although I appreciate the vote of confidence with the “when” rather than the much-more-deserved-and-appropriate “if,” that the odds of me ever writing comics period are small. There are two ways to break into writing comics for the “majors”: either be very successful at writing other media or be reasonably successful at writing comics on an independent basis. Given the arc of my career both as a writer and in everything else, I simply don’t have the time to pursue the second and the first, while certainly possible, remains unlikely.

I say this not to disparage myself, because I am awesome of course, but to remind anybody watching that “I Should Write The Legion” exists, as it always has, for two reasons: for me to refine my storytelling and pitching process (because every post is, in essence, a practice pitch to an attentive audience – which, it should be noted, is different from pitching to, say, an editor), and for me to enthuse about how awesome the Legion of Super-Heroes is.

I would like to stress this to onlookers: if you want to write comics, for the love of Christ do not follow my example.

That having been said, to answer the question:

1.) with a bullet: Takeshi Miyazawa. If I had any authority at DC I would be offering Miyazawa fucking gobs of money to come draw Teen Titans or Legion or Supergirl or Robin or anything with teenaged heroes in it; I can’t think of any comic artist working today who so excellently marries the manga artistic style with the Western superhero style. Other artists might be able to likewise draw the shit out of the Legion, but I can’t think of anybody else whose art in and of itself carries with it the potential to expand the reading audience just by its very nature. (Plus, Miyazawa is just fucking amazing and I would love to see him draw Brainiac Five.)

2.) Adrian Alphona. Is he even doing anything right now? Regardless, I love his designs and his detailed-yet-distorted artistic style. AND he can keep to a monthly schedule, which earns big points in my book.

3.) Michael Ryan. The fact that I have listed three artists in a row who are notable for working on Runaways is not an accident; Marvel have done a ridiculously good job giving that book excellent artists who are capable of drawing teenaged superheroes without having them appear too adult or too infantile. Ryan’s backgrounds are crazy good.

4.) Skottie Young. I just love his stuff. I know this is not a universally shared opinion, but so what – it’s my list, nyah nyah nyah. I think he would draw a wicked awesome Shadow Lass. And a wicked awesome Blok. And a super-double-plus wicked awesome Validus. And the lightning effects for Lightning Lad! Just imagine what Skottie Young would do with THAT shit!

5.) David Baldeon. Apparently currently the artist on Robin, which I don’t read regularly, but he also filled in on an issue of Blue Beetle a while back and I really loved his clean character work and design sense. Reminds me of a more stylized Chris Batista in a way.

So that’s my top five. There are plenty of others I could rattle off: Amanda Conner, Freddie Williams III, Peter Snejberg, Chris Sprouse, even Mike Krahulik. And Francis Manapul is excellent, and his only downside is that it’s only a matter of time before he’s transferred to a higher-profile title. But it’s all moot, anyway, so in the end I vote for whichever one that will give me money and power and women.

9

Jul

Let’s talk about a core character.

A lot of Legion purists think that the Legion is not the Legion without Superboy. Needless to say, I am not one of them.

Don’t get me wrong, I love all the old Superboy and the Legion comics from back in the day, and the premise is sound, but sometimes you just have to point at something and say, “no, not now.” Superboy in the Legion is a “no, not now,” because the comics market has shifted in terms of what readers expect – and this isn’t just a “cater to the hardcores” move either, because the one thing old comics readers and new share alike is the desire to sense that the comics they are reading “matter.”

Now, of course, the comics themselves can’t “matter,” because we all know the drill – it’s a sequential, serial art form. Illusion of change. And so forth. But “mattering” isn’t about the end result, but rather the suspension of disbelief. It doesn’t matter that at the end of the day, deaths are frequently written away and reversed, that character positions remain static by corporate design. What matters is that we can forget about that and indulge ourselves in a story that has the illusion of real change.

Well, guess what: Superboy sucks at that. It’s really hard to suspend disbelief in static continuity when one of the stars of your comic magazine for certain is going to be fine, because he has to grow up to be Superman like we all know he does. It’s not a coincidence that the Legion’s most universally acclaimed creative period (Paul Levitz’s run) as well as its most creatively experimental (Keith Giffen’s v4) happened mostly or entirely without Superboy.

When people accept this, their first instinct is to turn to a replacement Superboy. Bring Kon-El back from the dead! Have Chris Kent grow up and become the future Superboy! These have the wonderful ability to be lose-lose situations, because the hardcores are going to bitch and whine about a replacement Superboy who isn’t “the real one” and everybody else is going to look at the poor writer desperately shoehorning in some total nobody replacement Superboy and say “oh, they’re just catering to the hardcores.”

However, Supergirl, on the other hand, has absolutely none of that baggage. And indeed, I’m going to argue that the Legion is not only a good place for her to be, comics-wise, but indeed the best place to be.

For starters: quick, name Supergirl’s place in the modern-day DC Universe. Trick question: she doesn’t have one. She’s been shuffled around from team to team (the Outsiders? the Teen Titans? the new Justice League comic James Robinson is writing?) and been given half a dozen characterizations (none of which have really worked that well). From a functional standpoint it makes sense to put her in the future, because in the future there won’t be a dozen writers all trying to put together her personality from scratch at once.

But it also works from a literary standpoint as well. Supergirl can fill the role that Superboy used to fill: the inspiration of the Legion made flesh. (Okay, so she’s not Superman, but so what? She’s not exactly no big deal, you know.) But in addition to that she works as a character in the Legion in her own right. Given that I’ve previously mentioned how much I love the concept of Alexis Luthor, a natural rivalry is right there: the heir of Luthor versus a timelost survivor of the El family. And of course, using Supergirl offers one the chance to finally explore her relationship with Brainiac Five properly, and truthfully I think there’s a story there that could simply be epic.

But mostly I like it because in the Legion, Supergirl isn’t redundant (as she so painfully is in the modern day DCU, a marketing gimmick roughly transformed into a character with her own, frequently unreadable comic). In the Legion, Supergirl is the big gun. She’s the living reminder of why the Legion exists in the first place. She’s in the one place where she can finally live up to her own potential without having her cousin outshine her constantly.

Oh, and one more thing.

She arrives in the future – once again – by accident. And while she’s there, she learns something: less than a day after her return to the past, she’ll die. In a manner befitting a superhero, saving an entire galaxy, to be sure. But she’ll die, you can be sure of that. She can’t stay in the future forever – sooner or later the timestream will start to stress and fracture if she doesn’t go fulfill her destiny. She is marked.

So while she’s in the future, she decides to help as many people as possible. That’s what a superhero does, and Supergirl is a superhero – and in the future, she’ll finally get the chance to be a legendary one.

EDIT TO ADD: Hoo boy.

Well, now that “women in refrigerators” comments have started to show up along with the flame mail, let me re-emphasize a paragraph:

It doesn’t matter that at the end of the day, deaths are frequently written away and reversed, that character positions remain static by corporate design. What matters is that we can forget about that and indulge ourselves in a story that has the illusion of real change.

Let me further add that characters being fated to die is not precisely the same as killing them off. Even if it is part of history, it’s not carved in stone. I seem to remember this season of Doctor Who promising the death of a companion and weaseling out of it. (Not particularly well, if we’re being honest, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t ways to do it and have it be satisfying.)

Supergirl in the Legion means she’s on one of the most (and maybe the most) powerful superteams in comic history. Do you seriously think they wouldn’t have something to say about that? Do you seriously think Brainy, the smartest person in history, wouldn’t stretch his intellect to the breaking point to find an escape hatch?

Superhero comics are fundamentally about doing the impossible in the name of the greater good, six times before breakfast. This is just the most extreme iteration of that. I’m not going to say whether or not the Legion would succeed at finding a way to prevent Supergirl’s death. (Suspension of disbelief. Also, not giving away the cow. Et cetera.) But they would try. And that’s the important thing.

24

Jun

The multiverse moves. It moves around itself. Think of it as an enormous wheel – you can most easily travel to any point on the wheel by traveling to and from the center. Which just means you need a way to get to the center. That’s why I called my ship the Spoke. Of course, my metaphor is actually in reality completely inaccurate, and in retrospect, I should called it “the Axle.” But you get the gist.

Dr. Jonathan Dhir is a genius; a master of transdimensional physics, one of the very few to ever take that knowledge out of the realm of theory and into the practical. He’s likewise a good man, brave and smart. Maybe a bit obsessive, as some scientists tend to be. But not a bad man by any stretch.

His only problem is that his wife is dead.

Some have said there are fifty-two universes; this is thinking small. The megaverse roams in clusters of fifty-two universes at a time. Some are completely barren of all life. Some do not entirely conform to our concept of physics. One is made entirely out of jelly. No, I’m not joking about that last one. It’s really made out of jelly. Not edible jelly, mind you. But jelly.

Dhir and his wife – it was true love, the kind you only ever read about in storyscrolls. (They never really went to books in his universe, although they’ve long since computerized the process.) And Dhir was a genius, but not a universal one; he couldn’t cure the comaegulanara his wife contracted.

Ordinary people grieve and move on. But Dhir had other options most people don’t, and a certain sort of persistent quality that’s greatly magnified when you’re a brilliant scientist.

If anything can exist somewhere, that means it does. And that means if anyone can exist somewhere, that means they do.

He wasn’t sure if humans could safely traverse the boundaries of the multiverse, let alone the megaverse. When he launched the Spoke out of its orbit he calculated that there was a .7 percent chance it would blink into nothingness, and him along with it. He was willing to take the risk.

It took him a very long time, and he had many, many adventures along the way, becoming something of a hero in the process. He found universes where he and his wife both died as children, never even meeting. He found universes where his wife was alive, but unfortunately so was that universe’s version of himself, and he wasn’t the sort to intrude. He found universes where his wife was alive and he was dead, but unfortunately he was a dead woman and his wife and he were both gay. (That universe was awkward, but not so awkward as the universe where he and his wife were both arthropods.)

Of course it’s a moral act. Somewhere, there is a place where she is alone. She isn’t supposed to be alone.

Finally he found it, a universe where his wife was human (more or less), and not dead, and that universe’s version of himself died young in a war some time previous, never even meeting her. And she was lonely, and she couldn’t quite figure out how not to be lonely. She’d even joined this team of young heroes wearing gaudy costumes, trying to make the universe a better place, and he was amazed – if his wife had ever had superpowers, she would have done exactly that. He was sure of it.

Of course, now he’d have to convince her he wasn’t insane or psychotic – not to mention make her fall in love with him – and yes, that would probably be difficult. But Dr. Dhir is, if anything, a remarkably methodical and patient man.

I’ve seen the birth of species, the death of galaxies and the universe from the outside looking in. I’d trade all of those memories away for five minutes of her time – because to me, she is the universe. And I think I could be hers.

7

May

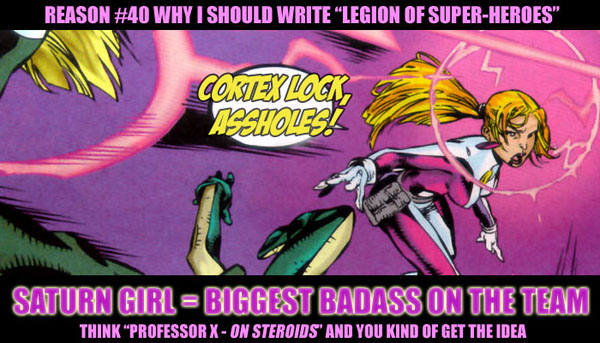

At the tail end of my last I Should Write The Legion, I promised that this one would feature the “biggest badass” in the Legion, and the guesses were predictable: Brainiac Five, of course, but also Superboy and Star Boy, plus a couple of emails betting it was Wildfire.

All of them are cool, mind you, but when you’re talking sheer badass that is off the charts, there’s only one nominee.

She’s a ridiculously powerful telepath. Her mental abilities have at times managed to hold off gods. She’s made entire groups of Legionnaires believe that missing comrades were alongside them for months at a time, lobotomized enemies, beaten other top-league telepaths like rented mules. In terms of sheer power, Imra Ardeen is near the top of any scale upon which the Legion can be judged.

(Aside: I remember someone once asked me to explain the appeal of the Legion. The conversation went like this. “Do you like Magneto?” “Yeah.” “Professor X?” “Yeah.” “Superman?” “Yeah.” “Wolverine?” “Yeah.” “Imagine all of them on the same team, together, plus Iceman and Firestar and Mr. Fantastic minus the stretching and a bunch of other equally powerful characters. That’s the Legion. They kick ass.”)

But what makes Saturn Girl the biggest badass in the Legion isn’t that she’s powerful. Lots of Legionnaires are powerful, after all. What makes her the biggest badass in the Legion is her inherent pragmatism – recently pointed out quite adeptly by Jim Shooter when she calmly mind-controlled Timber Wolf to stop him from killing somebody in a fit of rage, then mindwiped all the onlookers to make them forget that Timber Wolf snapped. Is this a violation of both T-Wolf and the assorted citizen’s mental dignity? Yes, that’s exactly what it was – and she did it anyway because it was necessary.

In his run initiating the current Legion, Mark Waid placed Cosmic Boy and Brainiac Five in opposition to one another. I always felt this missed the mark, because Cosmic Boy has the Captain America role in the Legion – he’s the guy the team rallies around, the purest and most natural leader, the one who is, by definition, going to be on the right side. Placing someone in opposition to Cosmic Boy is like, I dunno, putting Captain America on one side of a superhero-versus-superhero conflict and then asking readers not to think of the other side as the de facto “bad guys.” It made Brainiac Five seem almost villainous.

However, Brainy does need a counter in the Legion, because his intellectual and moral role within the team is so powerful, and Saturn Girl is exactly the person to take on the job. She’s tough and smart, and her steady pragmatism is the perfect foil for Brainy’s powerful idealism. The way I see it, there are things Brainiac Five just will not do as a matter of principle, even if they are necessary. (A great story in the initial-reboot Legion had him refuse to use the Metal Men’s responsometers to help the timelost Legion get home without their permission, once he realized they were sentient intelligences.)

Saturn Girl, on the other hand, is a lot more willing to bite the bullet. It’s just who she is. Which in turn means the two of them will be at odds with one another frequently. Not team-dividing warfare or anything; simply the collision of two equally valid yet ultimately opposed perspectives.

(Oh, and since I know people will ask: she’s with Lightning Lad because Garth is, in many ways, the Captain Carrot of the Legion – he’s not brilliant, but he’s moral and upright and just plain good, through and through. Do you really think a telepath could manage to be with anybody else?)

EDIT TO ADD: I didn’t want to elaborate too much on why Saturn Girl is pragmatic, but Brad pretty much explained it for me in comments below:

Saturn Girl isn’t pragmatic, because it’s an extention of her desire for control, or peace, or some kind of moral imperitive – she’s just been raised in a society that’s to some extent a psychic open-book. Much of our laws about freedom and rights (and justice) are because we can’t ever know what someone’s actual intent is behind their actions or what their capacity to act on those intents are. Titanians have no such limitations.

Exactly.

15

Apr

I might have mentioned this one before in passing, but since today is my Property exam I’m going to cheat a bit and use it.

There was a bit of a minor fan kerfuffle (nothing along the lines of the recent “that’s not how Dr. Doom talks” kerfuffle, you understand – this is the piddling, smallish sort of kerfuffle) recently regarding Shadow Lass in the most recent issue of Legion chopping an alien monster baddie thing to death with a giant poleaxe. You know, the “wait, Legionnaires aren’t supposed to kill” sort of kerfuffle.

And it’s fair that generally speaking, Legionnaires should not kill, even if they are the mean type of badass Legionnaire, and that generally killing in the pages of Legion should be reserved for extreme circumstances, like when Projectra needs to take care of Nemesis Kid in an old-school manner.

But Shadow Lass interests me, because Shadow Lass is from Talok VI, which is generally recognized in Legion lore – throughout pretty much all the reboots – as a semi-barbaric warrior culture. They’re not the Klingons of the DC Universe (we all know that the Khund are the Klingons of the DC Universe). But the Talokians are pretty direct when it comes to dealing with people they consider enemies. So, although I’m sure Shady isn’t going to go around executing people willy-nilly or even busting out the deadly weapons in a tougher than average fight, I can understand where her response to “oh shit a giant killer monster” is to go all Ripley on its ass.

And Talok is a warrior culture, and every Shadow Champion of the Talokians has died in glorious battle, and…

…wait, all of them died in glorious battle? How’s that again?

Well, it’s simple. See, the Shadow Champion has the shadow powers bestowed upon him or her when they’re selected. And then they have them until they die. (That thing a while back where other Talokians were challenging Tasmia for the shadow powers? Yeah, that’s kind of a ritual. The Talokian elders all know the real deal – that’s why the Shadow Champion never loses to the putzes who weren’t good enough to qualify.) And they have to die in battle –

– because that’s the only way they can die.

See, shadow powers in the DC Universe have a proud pedigree. There’s the Shade, and his evil opposite Culp. And Obsidian. And the thing about shadow powers is this: for some reason – maybe it’s their tie to the entropic forces gradually tearing apart the universe – if you’ve got them, you don’t age. And you’re definitely tough to kill. You tend to heal up from most wounds, although not exactly at Wolverine speed or anything like that.

Now, Talok’s a warrior culture. Warrior cultures tend to have Valhalla-type afterlife beliefs. You get to go to the good afterlife by dying in battle (or by ritualistic “battle”, no doubt, for the aged warriors on their deathbeds). But the shadow powers (which, needless to say, Shady and the other champions have never used to their full potential – the Shade is terrifyingly powerful, you know) make it essentially impossible to die normally in the course of battle, as is well and proper. Which is why most Shadow Champions grow progressively more suicidal as they figure out what they’ve become, flinging themselves into more and more dangerous attacks.

Now, this in and of itself is quite interesting (to me, anyway). But I’ll add on something else: Shady’s going to be needed for an adventure at the literal End of the Universe, temporally speaking. She has to learn to be the last Shadow Champion. She has to come to grips with living forever – something her culture, her entire upbringing, deems abhorrent. Something fundamentally opposite to who she is.

This is where one Richard Swift, Esq. steps in – because when life deals you a bum hand, often the best possible friend you can have is someone who’s already used to it, and who can help you deal with it, get used to it. Possibly also pass on his exceptional sartorial taste. (Well, that last probably won’t happen, much to the Shade’s chagrin.)

NEXT TIME: The biggest badass in the Legion.

2

Apr

Blame Greg Morrow for this one, and I’ll just quote him in the email he sent me:

You should write a “Why I should write LSH” about Starro. Pro or con. The Star Conqueror lies at the heart of DC Comics’ appeal, viz., it’s an adorably goofy idea that you can’t explain to a non-comics-reading adult without apologizing, but at the same time is amazingly effective and terrifying when played straight. (I’ve argued the same about Modok.)

What attracts me to the idea is that Starro is an alien invader. He’s intrinsically more SFnal than the usual run of supervillain, and the LSH should be more SFnal than the usual run of superhero comic. He’s also not a bumpy-forehead alien like the Khunds or the Skrulls, and, as Grant Morrison exploited, that makes him potentially a lot more alien, harder to understand and come to grips with as an antagonist, and therefore just plain scarier.

Greg is dead on with all of this, and until he mentioned something else in his email – namely, that we have no idea where Starro(s) come from – well. I’ll tell you the truth.

I’d considered Starro previously as an LSH villain, and dismissed him.

Not because I don’t love Starro. Starro is awesome. He is an evil space-traveling starfish. You don’t get more comics than that. But the problem with Starro is that the single most primal story from a comics standpoint that involves Starro – namely, that he takes over some of the superheroes and then the superheroes have to fight each other, Starro-controlled hero against still-independent hero – has been done quite a lot, and a new take on it has to be really brilliant, and I couldn’t think of one. Brad Meltzer did the “miniature Starros as mind-control agents” bit in his year on Justice League, so that’s out too.

And then Greg pointed out that we don’t know where Starro comes from, and that’s when I got the idea.

Why does Starro want to conquer, anyway? I mean, Starro is most terrifying when he’s so utterly fucking alien in motivation that he doesn’t bother explaining why he’s mind-controlling everybody with his starfish spawnlings. He just does it. Why would he do that?

Maybe it’s a biological imperative. Maybe Starro and/or his race feed off psychic emanations. A Starro creates the starfish spawn to serve much like tiny little suction cups. The mind-control evolved over time. First it was just a defense mechanism to keep people from tearing off the spawn, but it got finer and more astute over time, and then one day the Starros started getting smarter, and smarter, and smarter as they kept absorbing all that brain-juice, until they achieved sentience, and they realized that this was only the beginning.

Of course, Starro isn’t stupid, and probably after his nth asskicking at the hands of Earth superheroes he realized that straight-up conquest just wasn’t going to work. But here’s the thing about essentially immortal starfish: they can afford to play the long game.

Imagine a world, way off in a quiet corner of space, where Starro lives peaceably with an intelligent humanoid population. It’s a symbiotic relationship, much like the Trills in Star Trek. Starro gets to eat brain-energy, but in return he makes his hosts stronger, faster, healthier (and not everybody on the planet gets to be a host – the race considers it a privilege to carry a spawnling). A plain, quiet, orderly little world, polite and friendly – except over time Starro has become the absolute leader, and worse, he doesn’t have to force anybody this time around to let him be in charge. Think how goddamned creepy it would be.

A world where dissidents are punished – for their own good, of course, your loved ones will drag you to a faceful of starfish themselves if they have to, because they know it’s the best thing for you – with aggressive Starro therapy. (Dissidents tend to have more agitated brains. Nothing like a little Starro to sort that out and calm them down.) A world where every policeman has a starfish on his face that shoots a stun-ray from its central eye. A world where people compete for Starro’s attention.

This is a Starro who thinks beyond simple tactics like “take over everything in sight, then take over more things, then more, then more.” This is a Starro that’s figured out how to achieve his ultimate objective – soft tactics rather than hard force. The ultimate face of starfish fascism, brought about the way all good fascism is – entirely voluntarily.

And what is Starro’s ultimate objective? Why does he want to conquer everything, anyway?

Well, I can’t give it away for free, you know? 🙂

"[O]ne of the funniest bloggers on the planet... I only wish he updated more."

-- Popcrunch.com

"By MightyGodKing, we mean sexiest blog in western civilization."

-- Jenn